По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

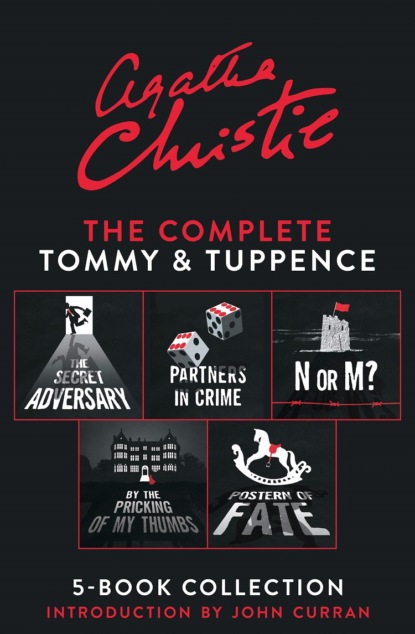

The Complete Tommy and Tuppence 5-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Tuppence interrupted him.

‘A pensionnat?’

‘Exactly. Madame Colombier’s in the Avenue de Neuilly.’

Tuppence knew the name well. Nothing could have been more select. She had had several American friends there. She was more than ever puzzled.

‘You want me to go to Madame Colombier’s? For how long?’

‘That depends. Possibly three months.’

‘And that is all? There are no other conditions?’

‘None whatever. You would, of course, go in the character of my ward, and you would hold no communication with your friends. I should have to request absolute secrecy for the time being. By the way, you are English, are you not?’

‘Yes.’

‘Yet you speak with a slight American accent?’

‘My great pal in hospital was a little American girl. I dare say I picked it up from her. I can soon get out of it again.’

‘On the contrary, it might be simpler for you to pass as an American. Details about your past life in England might be more difficult to sustain. Yes, I think that would be decidedly better. Then –’

‘One moment, Mr Whittington! You seem to be taking my consent for granted.’

Whittington looked surprised.

‘Surely you are not thinking of refusing? I can assure you that Madame Colombier’s is a most high-class and orthodox establishment. And the terms are most liberal.’

‘Exactly,’ said Tuppence. ‘That’s just it. The terms are almost too liberal, Mr Whittington. I cannot see any way in which I can be worth that amount of money to you.’

‘No?’ said Whittington softly. ‘Well, I will tell you. I could doubtless obtain someone else for very much less. What I am willing to pay for is a young lady with sufficient intelligence and presence of mind to sustain her part well, and also one who will have sufficient discretion not to ask too many questions.’

Tuppence smiled a little. She felt that Whittington had scored.

‘There’s another thing. So far there has been no mention of Mr Beresford. Where does he come in?’

‘Mr Beresford?’

‘My partner,’ said Tuppence with dignity. ‘You saw us together yesterday.’

‘Ah, yes. But I’m afraid we shan’t require his services.’

‘Then it’s off !’ Tuppence rose. ‘It’s both or neither. Sorry – but that’s how it is. Good morning, Mr Whittington.’

‘Wait a minute. Let us see if something can’t be managed. Sit down again, Miss –’ He paused interrogatively.

Tuppence’s conscience gave her a passing twinge as she remembered the archdeacon. She seized hurriedly on the first name that came into her head.

‘Jane Finn,’ she said hastily; and then paused open-mouthed at the effect of those two simple words.

All the geniality had faded out of Whittington’s face. It was purple with rage, and the veins stood out on the forehead. And behind it all there lurked a sort of incredulous dismay. He leaned forward and hissed savagely:

‘So that’s your little game, is it?’

Tuppence, though utterly taken aback, nevertheless kept her head. She had not the faintest comprehension of his meaning, but she was naturally quick-witted, and felt it imperative to ‘keep her end up’ as she phrased it.

Whittington went on:

‘Been playing with me, have you, all the time, like a cat and mouse? Knew all the time what I wanted you for, but kept up the comedy. Is that it, eh?’ He was cooling down. The red colour was ebbing out of his face. He eyed her keenly. ‘Who’s been blabbing? Rita?’

Tuppence shook her head. She was doubtful as to how long she could sustain this illusion, but she realized the importance of not dragging an unknown Rita into it.

‘No,’ she replied with perfect truth. ‘Rita knows nothing about me.’

His eyes still bored into her like gimlets.

‘How much do you know?’ he shot out.

‘Very little indeed,’ answered Tuppence, and was pleased to note that Whittington’s uneasiness was augmented instead of allayed. To have boasted that she knew a lot might have raised doubts in his mind.

‘Anyway,’ snarled Whittington, ‘you knew enough to come in here and plump out that name.’

‘It might be my own name,’ Tuppence pointed out.

‘It’s likely, isn’t it, that there would be two girls with a name like that?’

‘Or I might just have hit upon it by chance,’ continued Tuppence, intoxicated with the success of truthfulness.

Mr Whittington brought his fist down upon the desk with a bang.

‘Quit fooling! How much do you know? And how much do you want?’

The last five words took Tuppence’s fancy mightily, especially after a meagre breakfast and a supper of buns the night before. Her present part was of the adventuress rather than the adventurous order, but she did not deny its possibilities. She sat up and smiled with the air of one who has the situation thoroughly well in hand.

‘My dear Mr Whittington,’ she said, ‘let us by all means lay our cards upon the table. And pray do not be so angry. You heard me say yesterday that I proposed to live by my wits. It seems to me that I have now proved I have some wits to live by! I admit I have knowledge of a certain name, but perhaps my knowledge ends there.’

‘Yes – and perhaps it doesn’t,’ snarled Whittington.

‘You insist on misjudging me,’ said Tuppence, and sighed gently.

‘As I said once before,’ said Whittington angrily, ‘quit fooling, and come to the point. You can’t play the innocent with me. You know a great deal more than you’re willing to admit.’

Tuppence paused a moment to admire her own ingenuity, and then said softly:

‘I shouldn’t like to contradict you, Mr Whittington.’

‘So we come to the usual question – how much?’