По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

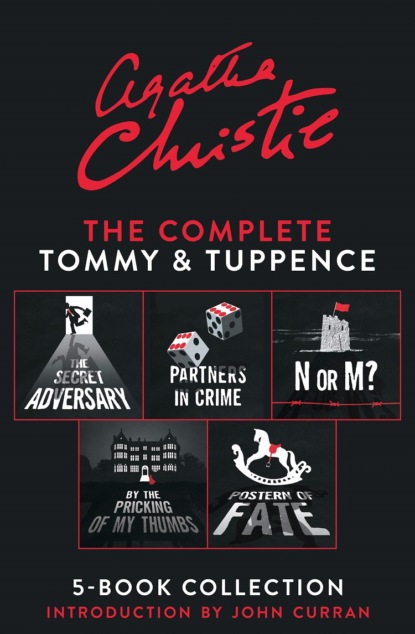

The Complete Tommy and Tuppence 5-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Excuse me,’ it said. ‘But may I speak to you for a moment?’

Chapter 2 (#ulink_5a217902-fcb3-50f9-87a8-75e2bb46ae47)

Mr Whittington’s Offer (#ulink_5a217902-fcb3-50f9-87a8-75e2bb46ae47)

Tuppence turned sharply, but the words hovering on the tip of her tongue remained unspoken for the man’s appearance and manner did not bear out her first and most natural assumption. She hesitated. As if he read her thoughts, the man said quickly:

‘I can assure you I mean no disrespect.’

Tuppence believed him. Although she disliked and distrusted him instinctively, she was inclined to acquit him of the particular motive which she had at first attributed to him. She looked him up and down. He was a big man, clean shaven, with a heavy jowl. His eyes were small and cunning, and shifted their glance under her direct gaze.

‘Well, what is it?’ she asked.

The man smiled.

‘I happened to overhear part of your conversation with the young gentleman in Lyons’.’

‘Well – what of it?’

‘Nothing – except that I think I may be of some use to you.’

Another inference forced itself into Tuppence’s mind.

‘You followed me here?’

‘I took that liberty.’

‘And in what way do you think you could be of use to me?’

The man took a card from his pocket and handed it to her with a bow.

Tuppence took it and scrutinized it carefully. It bore the inscription ‘Mr Edward Whittington.’ Below the name were the words ‘Esthonia Glassware Co.,’ and the address of a city office. Mr Whittington spoke again:

‘If you will call upon me tomorrow morning at eleven o’clock, I will lay the details of my proposition before you.’

‘At eleven o’clock?’ said Tuppence doubtfully.

‘At eleven o’clock.’

Tuppence made up her mind.

‘Very well. I’ll be there.’

‘Thank you. Good evening.’

He raised his hat with a flourish, and walked away. Tuppence remained for some minutes gazing after him. Then she gave a curious movement of her shoulders, rather as a terrier shakes himself.

‘The adventures have begun,’ she murmured to herself. ‘What does he want me to do, I wonder? There’s something about you, Mr Whittington, that I don’t like at all. But, on the other hand, I’m not the least bit afraid of you. And as I’ve said before, and shall doubtless say again, little Tuppence can look after herself, thank you!’

And with a short, sharp nod of her head she walked briskly onward. As a result of further meditations, however, she turned aside from the direct route and entered a post office. There she pondered for some moments, a telegraph form in her hand. The thought of a possible five shillings spent unnecessarily spurred her to action, and she decided to risk the waste of ninepence.

Disdaining the spiky pen and thick, black treacle which a beneficent Government had provided, Tuppence drew out Tommy’s pencil which she had retained and wrote rapidly: ‘Don’t put in advertisement. Will explain tomorrow.’ She addressed it to Tommy at his club, from which in one short month he would have to resign, unless a kindly fortune permitted him to renew his subscription.

‘It may catch him,’ she murmured. ‘Anyway it’s worth trying.’

After handing it over the counter she set out briskly for home, stopping at a baker’s to buy three-pennyworth of new buns.

Later, in her tiny cubicle at the top of the house she munched buns and reflected on the future. What was the Esthonia Glassware Co., and what earthly need could it have for her services? A pleasurable thrill of excitement made Tuppence tingle. At any rate, the country vicarage had retreated into the background again. The morrow held possibilities.

It was a long time before Tuppence went to sleep that night, and, when at length she did, she dreamed that Mr Whittington had set her to washing up a pile of Esthonia Glassware, which bore an unaccountable resemblance to hospital plates!

It wanted some five minutes to eleven when Tuppence reached the block of buildings in which the offices of the Esthonia Glassware Co. were situated. To arrive before the time would look over-eager. So Tuppence decided to walk to the end of the street and back again. She did so. On the stroke of eleven she plunged into the recesses of the building. The Esthonia Glassware Co. was on the top floor. There was a lift, but Tuppence chose to walk up.

Slightly out of breath, she came to a halt outside the ground glass door with the legend painted across it: ‘Esthonia Glassware Co.’

Tuppence knocked. In response to a voice from within, she turned the handle and walked into a small, rather dirty office.

A middle-aged clerk got down from a high stool at a desk near the window and came towards her inquiringly.

‘I have an appointment with Mr Whittington,’ said Tuppence.

‘Will you come this way, please.’ He crossed to a partition door with ‘Private’ on it, knocked, then opened the door and stood aside to let her pass in.

Mr Whittington was seated behind a large desk covered with papers. Tuppence felt her previous judgment confirmed. There was something wrong about Mr Whittington. The combination of his sleek prosperity and his shifty eye was not attractive.

He looked up and nodded.

‘So you’ve turned up all right? That’s good. Sit down, will you?’

Tuppence sat down on the chair facing him. She looked particularly small and demure this morning. She sat there meekly with downcast eyes whilst Mr Whittington sorted and rustled amongst his papers. Finally he pushed them away, and leaned over the desk.

‘Now, my dear young lady, let us come to business.’ His large face broadened into a smile. ‘You want work? Well, I have work to offer you. What should you say now to £100 down, and all expenses paid?’ Mr Whittington leaned back in his chair, and thrust his thumbs into the arm-holes of his waistcoat.

Tuppence eyed him warily.

‘And the nature of the work?’ she demanded.

‘Nominal – purely nominal. A pleasant trip, that is all.’

‘Where to?’

Mr Whittington smiled again.

‘Paris.’

‘Oh!’ said Tuppence thoughtfully. To herself she said: ‘Of course, if father heard that he would have a fit! But somehow I don’t see Mr Whittington in the rôle of the gay deceiver.’

‘Yes,’ continued Whittington. ‘What could be more delightful? To put the clock back a few years – a very few, I am sure – and re-enter one of those charming pensionnats de jeunes filles with which Paris abounds –’