По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

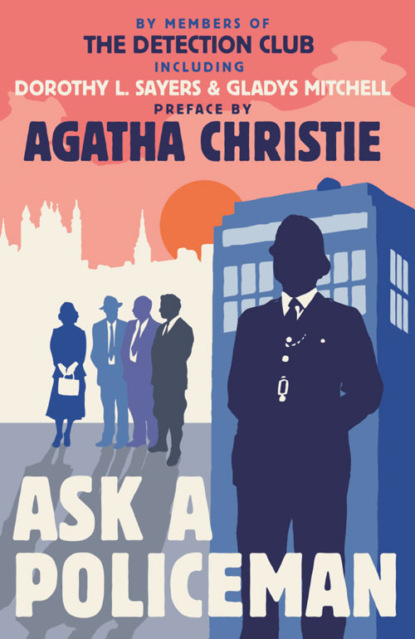

Ask a Policeman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Commissioner turned his attention to Mills. “Do you know where Lord Comstock dined last night?” he asked.

“I don’t. Certainly not at Hursley Lodge. He went out with the chauffeur in the car about seven, and did not come back till midnight. He was not in the habit of informing me of his movements unless for some definite purpose.”

“You appear to have examined Lord Comstock’s body fairly closely, Farrant?”

“I bent down to pick him up, sir, before I realized that he was dead.”

“Did you disturb it at all?”

“I moved the chair a bit to one side, sir, and I may have shifted the body slightly, but not so that one would notice it. And I dare say I pushed in the drawer an inch or two, so that I could get round to His Lordship.”

“What drawer was this, Farrant?”

“One of the drawers of the desk, sir, that was pulled nearly right out.”

The Commissioner looked at Easton. “You said nothing of this drawer being open in your report, Superintendent,” he said accusingly.

“When I entered the room, sir, all the drawers in the desk were shut, sir,” replied Easton positively.

“Well, having disturbed everything, you thought it time to call Mr. Mills,” continued the Commissioner. “Are you quite sure that you touched nothing else first?”

“Perfectly sure, sir,” Farrant replied.

“Was the drawer that Farrant mentions open when you came on the scene, Mr. Mills?”

“I did not notice it at the moment. I was too much concerned with Lord Comstock’s condition. I could see at a glance that he was dead. I immediately sent Farrant to the telephone in the hall, with orders to ring up the police-station.”

“In the hall! Is there no telephone in the study, then?”

“An extension. The main instrument is in the hall.”

“The extension would have served the purpose equally well, I should have thought. Had you any reason for getting Farrant out of the room?”

“Well, yes, I had. I had noticed by then that one of the drawers of the desk was slightly open, and I knew it to be the one in which Lord Comstock kept documents of a highly confidential nature. Upon Farrant leaving the room, I opened the drawer wide, and found the documents it contained lying in great disorder. I looked them over rapidly, and then shut the drawer.”

“Have you any reason to suppose that any of the documents it should have contained were missing?”

“I do not know what documents it contained. But all those I found, though highly confidential, had passed through my hands at one time or another. But I have my own reasons for believing that it had contained something of an even more confidential nature.”

“I should like to hear those reasons, Mr. Mills.”

“I may be wrong. But, when I entered the study earlier in the morning to announce the arrival of His Grace, that drawer was wide open and Lord Comstock was bending over it. As soon as he heard me, he slammed it violently. I certainly got the impression, at the time, that there was something in it that he did not wish me to see. Something particularly private, other than the documents which had passed through my hands already, I mean.”

“Then, if your suspicions are correct, it would appear that those documents have been stolen,” said the Commissioner weightily. “That is, unless Lord Comstock himself removed them and placed them elsewhere. This incident of the drawer may prove to be of some importance. You appear to have been somewhat overzealous, Mr. Mills. You should have left the drawer as you found it. Did you touch anything else in the study before the arrival of the police?”

Mills shook his head. “Nothing whatever,” he replied sullenly.

At this Farrant, who had been listening attentively to the conversation, coughed decorously. “Excuse me, gentlemen,” he said. “But I think Mr. Mills has forgotten the telephone?”

The Commissioner turned upon him. “What do you mean, Farrant? What telephone?”

“The private telephone, sir. Mr. Mills was using it when I came back from the hall.”

To Sir Philip, who had been a silent spectator of the scene, it had been apparent from the first that there was no love lost between the secretary and the butler. His pencil moved more deliberately than ever as he awaited developments.

“Oh, so there is a private telephone,” said the Commissioner. “Where does it lead to?”

It was Mills who answered him. “Fort Comstock. Naturally it was my duty to ring up the chief editor, and inform him of Lord Comstock’s death. That was hardly touching anything in the study, in the sense you mean.”

“Did you speak to anybody at Fort Comstock besides the chief editor?”

Mills hesitated. “Well, yes,” he replied defiantly. “I spoke to the crime expert of the Daily Bugle, and gave him a short account of the events of this morning.

This statement fell like a bomb among the Scotland Yard contingent. Audible mutters came from the corner where Shawford and Churchill were sitting together, and it was only by an obvious effort that the Commissioner restrained himself. He contented himself with a glance at Sir Philip, on whose lips something very like a smile was visible. Then he turned to Farrant. “You overheard this conversation? “he asked sharply.

“A bit of it, sir. I wondered why Mr. Mills should take so much trouble to tell his Lordship’s people and nobody else.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Well, sir, Mr. Mills had been given notice by his Lordship,” replied Farrant malevolently. “I heard his Lordship tell him so at lunch yesterday. Something about selling information to rival newspapers, it was, sir.”

“Is this a fact, Mr. Mills?” the Commissioner asked.

“It is certainly a fact that Lord Comstock threatened me with dismissal at lunch yesterday. He had just seen something in one of the rival papers which he believed to be known only to himself. He accused me of having sold this information for my own benefit. But I did not treat his outburst seriously. Similar incidents have occurred before.”

The Commissioner shrugged his shoulders. He had a feeling that the inquiry was straying from its proper course. In order to bring it back to realities he turned to Easton. “You made certain investigations outside the house, I believe?” he asked curtly.

“Yes, sir. I thought it possible that Lord Comstock might have been shot by somebody from outside the house, through the open windows of the study. As you can see by the plan, sir, there are no doors leading from the house directly on to the lawn. The back doors lead out of the house on the opposite side. Anyone wishing to reach the lawn would have to pass through two gates, one leading into the kitchen garden, the other from the kitchen garden to the lawn. Alternatively, he would have to climb the wall at the south-eastern corner of the house. That is, of course, sir, if he did not pass round the front of the house.”

The Commissioner, who had been looking over Sir Philip’s shoulder at the plan on the desk, nodded. “Yes, I see; go ahead, Easton.”

“Well, sir, there were no marks on the flower-beds below this wall, and no sign of anyone having climbed it. It is seven feet high, and would be difficult to climb in any case, without assistance. The gate between the kitchen garden and the lawn was locked. It is a heavy wrought-iron affair, and I was informed that only two keys to this exist. One was produced by the gardener to whom I spoke. The other I found upon Lord Comstock’s desk.”

Sir Philip looked up. “It doesn’t look as if anybody had reached the lawn from that direction, does it, Easton?” he remarked pleasantly. “And yet we have heard of somebody “—there was a significant emphasis upon this word—” of somebody who appeared upon the lawn. He must have come round by the front of the house, I suppose?”

“I think not, sir,” replied Easton, glancing at the Commissioner. “The gardener—”

“Oh, the gardener has something to say, has he? Have you got him outside, Hampton? Bring him in, if so. We’ll hear his story from his own lips.”

So the gardener, an incongruous figure in that solemn room, was introduced. But his evidence tended to make things still more obscure. He had been working all the morning at the flower-beds beside the drive. Two or three motors had passed him, but he hadn’t taken any heed of them. He hadn’t expected his Lordship down that week, and he was late with the bedding-out. His Lordship had given him a proper dressing-down because there wasn’t a good show of flowers. He was too busy to take much notice of motor cars and such.

“But you would have noticed if anybody had walked on to the lawn, I suppose?” asked the Commissioner impatiently.

“I couldn’t very well help noticing the lady when she stopped and watched what I was doing. She didn’t say nothing, though, and I couldn’t say who she was. I don’t mind that I ever saw her before.”

Sir Philip looked up and caught the Commissioner’s eye. The fact that there was a lady in the case was a further complication. And it was very curious that neither Mills nor the butler had mentioned her presence. But the Commissioner was alert enough to display no surprise.

“Oh yes, the lady, of course,” he said rather vaguely. “Do you remember what time it was when you saw her?”