По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

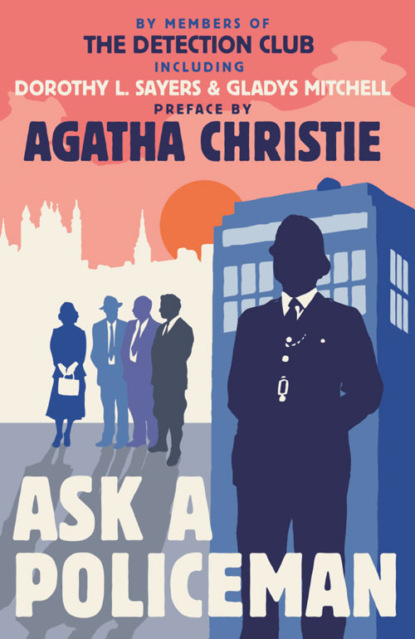

Ask a Policeman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Did you attach any significance to this crash at the time?”

“I did not. Lord Comstock, when he was roused, had a habit of picking up, say, a chair and banging it down on the floor, in order to emphasise his remarks. If I thought about the sound at all, I attributed it to some incident of this nature. I left the office, and went into the hall. As I did so, the door of the study into the hall opened violently, and His Grace appeared. He slammed the door behind him, and seemed for some moments unaware of my presence. He strode towards the front door, and I heard him distinctly say, twice, ‘The wages of sin.’”

“I overtook His Grace before he reached the front door, and asked him if he had a car waiting, or whether I should telephone for a taxi. But he seemed hardly to hear me. He shook his head, then walked rapidly down the drive towards the gate. I watched him until he passed out of sight, and then went back into the hall.”

“The Archbishop’s interview seems hardly to have been satisfactory,” Sir Philip remarked. “But it is curious that he should have refused the offer of a taxi. He can hardly have proposed to walk all the way back to his Province. Ah, but wait a minute, though. Convocation is sitting at Lambeth Palace, isn’t it! I forgot that for the moment. That explains Dr. Pettifer’s presence in the neighbourhood of London. How far is Hursley Lodge from the nearest station, Mr. Mills?”

“About a mile, sir, and it is almost twenty minutes from there to London by train.”

Sir Philip nodded. “No doubt the Archbishop is at Lambeth Palace by now. But, after his departure, you had the other two visitors to deal with. How did you proceed, Mr. Mills?”

“I had come to the conclusion that it would be best to introduce them without previously mentioning their presence to Lord Comstock, sir. They would then at least have a chance of explaining their insistence. As I passed through the hall after seeing His Grace off, I opened the drawing-room door. My intention was to tell Mr. Littleton that Lord Comstock was now disengaged, and that I would take the risk of showing him into the study. But then I remembered that Sir Charles Hope-Fairweather had the first claim, and that possibly Lord Comstock would be less displeased to see him than Mr. Littleton.”

“What made you think that, Mr. Mills?” asked Sir Philip quietly.

If he had expected to catch Mills out, he was disappointed. “It occurred to me, sir, that if Sir Charles was a personal friend, Lord Comstock’s refusal to see visitors might not apply to him.”

“Very well, you determined to give Hope-Fairweather the preference. You fetched him from the waiting-room and ushered him into the lion’s den?”

“Not exactly, sir. I had opened the door of the drawing-room, but on thinking of Sir Charles I shut it again, thankful that I was able to do so before Mr. Littleton had time to interrogate me. I had not seen him when I glanced into the room.”

“One moment, Mr. Mills. I should like you to explain that point a little more fully. As I understand you, you opened the door, glanced in, and shut it hastily. Was the whole of the room visible to you from where you stood?”

“Not the whole of it, sir. The half-open door hid the wall between the drawing-room and the study from me. If Mr. Littleton had been standing close to that wall, I might not have seen him.”

The Commissioner glanced at Sir Philip, who nodded, almost imperceptibly. Then he addressed Mills sharply. “At the moment when you opened the door, you would have been surprised to find the room empty. Any suggestion that that was the case would have impressed itself upon you. Yet you shut the door again without making further investigations?”

“I did. As I have explained, I was anxious to see Sir Charles before Mr. Littleton. I was still in the hall, when I heard a second crash, not dissimilar from the first. For a moment I thought it came from the study, and the thought flashed through my mind that Mr. Littleton, overhearing the departure of His Grace, might have carried out his threat, and entered the study unannounced through the door between that room and the drawing-room.”

The Commissioner interrupted him, this time without ceremony. “But that door is concealed by a bookcase, is it not?” he asked.

“On the study side, yes. The drawing-room is panelled, and the door is so arranged as to form one of the panels. It has no handle, but a concealed fastening, operated by sliding part of the framework of the panel.”

“In fact, a stranger would not perceive that it was a door at all?”

“Not at first sight, perhaps. But very little investigation would show him that the panel could be opened.”

Sir Philip began to show signs of impatience. “That, surely, is a matter which can be decided on the spot,” he said. “Please continue your narrative, Mr. Mills. Did you proceed to investigate the cause of this second crash?”

“I ran into my office, sir, and there, to my astonishment, found Sir Charles Hope-Fairweather. He was bending down and picking up a litter of papers which lay on the floor. The door leading into the waiting-room was open. Sir Charles, who appeared to be very much embarrassed, explained to me that he had entered the office to tell me that he could wait no longer. As he did so, he had stepped on a mat which had slipped beneath him on the polished floor. To save himself from falling he had clutched at a table which stood just inside the door, and on which was a wooden tray containing papers. This, however, had failed to save him, and he had fallen, dragging the table and tray down with him.”

“Would this have accounted for the crash you heard?” inquired the Commissioner.

“It might have done so. In fact, it seemed to me at the time a likely explanation of the crash.”

“You said just now that Sir Charles was wearing gloves when he entered the house. Was he still doing so?”

“Yes, he was. I noticed that as I dusted him down after his fall. A minute or two later, I escorted him through the hall to the front door, and immediately hurried back to the drawing-room.”

“Littleton’s turn had come, certainly,” remarked Sir Philip.

“That is what I thought, sir. My idea was to make one more effort to induce him to go away without seeing Lord Comstock, and if I failed, to introduce him. I walked into the drawing-room, to find it empty.”

“Upon my word, your visitors seem to have wandered about the house as if it was their own!” exclaimed Sir Philip. “There was no doubt this time that the room was really empty, I suppose? Littleton wasn’t hiding under the sofa? You can never tell what a policeman may do, you know.”

“The room was certainly empty, sir, and the concealed door into the study was shut. I could only conclude that Mr. Littleton had passed through it into the study. He had certainly not left the house, for his car was still in the drive when I saw Sir Charles off at the front door.”

“Where was Littleton’s car standing?” asked Sir Philip, glancing at the plan.

“A few yards south of the front door, sir. Almost immediately in front of the dining-room window. I went to the east window of the drawing-room, and looked out to see if the car was still there, and found that it was. A plot of grass, with a clump of tall beeches growing in it, hides the farther sweep of the drive from the windows of the house, sir. As I looked out I saw a big saloon car come out from behind it, and head for the gate. I recognized the driver as Sir Charles Hope-Fairweather, by the colour of his coat.

“A moment later, sir, I saw Mr. Littleton. He appeared round the north-east corner of the house, running as hard as he could across the lawn towards the front door. He jumped into his car, swung round the trees, and set off towards the gate at a reckless speed.”

“But this is most extraordinary, Mr. Mills. Where did you imagine that Littleton had come from?”

It seemed that Mills had prepared an answer to this question. At all events, his reply was ready enough. “I imagined that he must have left the house by the front door, and gone round on to the lawn, while I was helping Sir Charles to brush his clothes, sir. As soon as I had lost sight of Mr. Littleton’s car, I went back to my office.”

“You did not go into the study?” asked the Commissioner quickly.

“There was no reason to do so. Sir Charles and Mr. Littleton had gone, and I had no desire to disturb Lord Comstock unnecessarily. I certainly expected him to ring for me and inquire what Mr. Littleton had been doing on the lawn, since I thought he must infallibly have seen him. But, since he did not do so, I resumed my work.”

“Which had suffered considerable interruption,” Sir Philip remarked. “What time was it by then?”

“I glanced at the clock as I sat down, sir. It was then twenty-two minutes past twelve. I did not move from my chair again until about five minutes past one, when Farrant flung open the doors leaning into the study, and shouted to me to come in.”

“Ah, yes, the butler,” said Sir Philip thoughtfully. “Have you got him outside, Hampton? If so, he had better come in.”

The Commissioner went to the Private Secretary’s room and came out followed by an elderly man with a melancholy, almost morose, expression. It struck Sir Philip that Comstock had not been very fortunate in his choice of subordinates. Mills, in spite of his apparent candour, had not impressed him. There was a shifty look in his eyes that the Home Secretary did not quite like. And as for Farrant—well, there was nothing against him yet. But then, from all accounts, no self-respecting person would remain in Comstock’s household any longer than he could help. Sir Philip caught the Commissioner’s eye, and nodded slightly.

“Now, Farrant,” said the latter briskly, “I understand that you were the first to discover Lord Comstock’s death. How did this come about?”

“Punctually at one o’clock, sir, I came to inform his Lordship that lunch was on the table. I opened the study door, sir—”

“How did you reach the study, Farrant?” the Commissioner interrupted.

“I entered the hall by the service door from the kitchen, under the stairs, sir. The door of the study is nearly opposite. I opened this door, sir, and the first thing I saw was his Lordship lying on the floor by the window, with his chair half on top of him, sir. I ran up to him, thinking he had fallen over in a fit or something, sir. And then as soon as I looked at him and saw his head, I knew that he had been shot dead. And then I ran to the waiting-room and called Mr. Mills.”

“You knew that he had been shot dead, did you? And how did you know that?”

The sharp question seemed to confuse Farrant. “Why, sir, there was the wound, and the blood round it. And his Lordship was lying in a way he wouldn’t have been if he hadn’t been dead.”

“Yes, dead with a wound in his head, Farrant. But why shot dead?”

Farrant’s eyes strayed to the pistol, in full view on the Home Secretary’s desk. “I knew there was a pistol in the room, sir,” he replied confidently.

“Oh, you knew that, did you? When did you first see it there?”

Farrant glanced towards the chair in which Mills was sitting. “I saw it there yesterday evening, sir. I took the opportunity of tidying up the study then, since his Lordship had gone out to dinner.”