По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

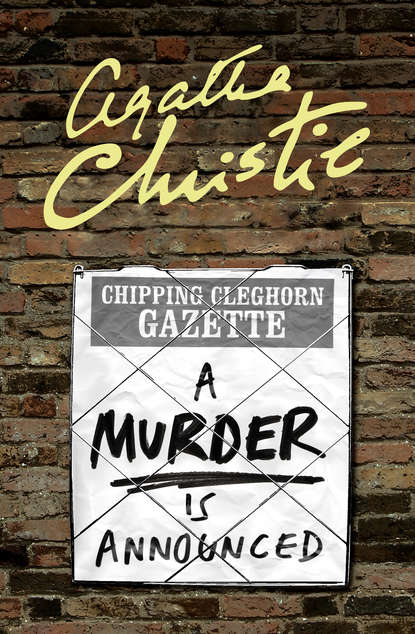

A Murder is Announced

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It’s a fine murdering day, (sang Bunch)

And as balmy as May

And the sleuths from the village are gone.’

A rattle of crockery being dumped in the sink drowned the next lines, but as the Rev. Julian Harmon left the house, he heard the final triumphant assertion:

‘And we’ll all go a’murdering today!’

CHAPTER 2 (#ud00fe465-4a5f-5c98-a2b9-c6f081d52cf5)

Breakfast at Little Paddocks (#ud00fe465-4a5f-5c98-a2b9-c6f081d52cf5)

At Little Paddocks also, breakfast was in progress.

Miss Blacklock, a woman of sixty odd, the owner of the house, sat at the head of the table. She wore country tweeds—and with them, rather incongruously, a choker necklace of large false pearls. She was reading Lane Norcott in the Daily Mail. Julia Simmons was languidly glancing through the Telegraph. Patrick Simmons was checking up on the crossword in The Times. Miss Dora Bunner was giving her attention wholeheartedly to the local weekly paper.

Miss Blacklock gave a subdued chuckle, Patrick muttered: ‘Adherent—not adhesive—that’s where I went wrong.’

Suddenly a loud cluck, like a startled hen, came from Miss Bunner.

‘Letty—Letty—have you seen this? Whatever can it mean?’

‘What’s the matter, Dora?’

‘The most extraordinary advertisement. It says Little Paddocks quite distinctly. But whatever can it mean?’

‘If you’d let me see, Dora dear—’

Miss Bunner obediently surrendered the paper into Miss Blacklock’s outstretched hand, pointing to the item with a tremulous forefinger.

‘Just look, Letty.’

Miss Blacklock looked. Her eyebrows went up. She threw a quick scrutinizing glance round the table. Then she read the advertisement out loud.

‘A murder is announced and will take place on Friday, October 29th, at Little Paddocks at 6.30 p.m.

Friends please accept this, the only intimation.’

Then she said sharply: ‘Patrick, is this your idea?’

Her eyes rested searchingly on the handsome devil-may-care face of the young man at the other end of the table.

Patrick Simmons’ disclaimer came quickly.

‘No, indeed, Aunt Letty. Whatever put that idea into your head? Why should I know anything about it?’

‘I wouldn’t put it past you,’ said Miss Blacklock grimly. ‘I thought it might be your idea of a joke.’

‘A joke? Nothing of the kind.’

‘And you, Julia?’

Julia, looking bored, said: ‘Of course not.’

Miss Bunner murmured: ‘Do you think Mrs Haymes—’ and looked at an empty place where someone had breakfasted earlier.

‘Oh, I don’t think our Phillipa would try and be funny,’ said Patrick. ‘She’s a serious girl, she is.’

‘But what’s the idea, anyway?’ said Julia, yawning. ‘What does it mean?’

Miss Blacklock said slowly, ‘I suppose—it’s some silly sort of hoax.’

‘But why?’ Dora Bunner exclaimed. ‘What’s the point of it? It seems a very stupid sort of joke. And in very bad taste.’

Her flabby cheeks quivered indignantly, and her short-sighted eyes sparkled with indignation.

Miss Blacklock smiled at her.

‘Don’t work yourself up over it, Bunny,’ she said. ‘It’s just somebody’s idea of humour, but I wish I knew whose.’

‘It says today,’ pointed out Miss Bunner. ‘Today at 6.30 p.m. What do you think is going to happen?’

‘Death!’ said Patrick in sepulchral tones. ‘Delicious death.’

‘Be quiet, Patrick,’ said Miss Blacklock as Miss Bunner gave a little yelp.

‘I only meant the special cake that Mitzi makes,’ said Patrick apologetically. ‘You know we always call it delicious death.’

Miss Blacklock smiled a little absent-mindedly.

Miss Bunner persisted: ‘But Letty, what do you really think—?’

Her friend cut across the words with reassuring cheerfulness.

‘I know one thing that will happen at 6.30,’ she said dryly. ‘We’ll have half the village up here, agog with curiosity. I’d better make sure we’ve got some sherry in the house.’

‘You are worried, aren’t you, Lotty?’

Miss Blacklock started. She had been sitting at her writing-table, absent-mindedly drawing little fishes on the blotting paper. She looked up into the anxious face of her old friend.

She was not quite sure what to say to Dora Bunner. Bunny, she knew, mustn’t be worried or upset. She was silent for a moment or two, thinking.

She and Dora Bunner had been at school together. Dora then had been a pretty, fair-haired, blue-eyed rather stupid girl. Her being stupid hadn’t mattered, because her gaiety and high spirits and her prettiness had made her an agreeable companion. She ought, her friend thought, to have married some nice Army officer, or a country solicitor. She had so many good qualities—affection, devotion, loyalty. But life had been unkind to Dora Bunner. She had had to earn her living. She had been painstaking but never competent at anything she undertook.

The two friends had lost sight of each other. But six months ago a letter had come to Miss Blacklock, a rambling, pathetic letter. Dora’s health had given way. She was living in one room, trying to subsist on her old age pension. She endeavoured to do needlework, but her fingers were stiff with rheumatism. She mentioned their schooldays—since then life had driven them apart—but could—possibly—her old friend help?

Miss Blacklock had responded impulsively. Poor Dora, poor pretty silly fluffy Dora. She had swooped down upon Dora, had carried her off, had installed her at Little Paddocks with the comforting fiction that ‘the housework is getting too much for me. I need someone to help me run the house.’ It was not for long—the doctor had told her that—but sometimes she found poor old Dora a sad trial. She muddled everything, upset the temperamental foreign ‘help’, miscounted the laundry, lost bills and letters—and sometimes reduced the competent Miss Blacklock to an agony of exasperation. Poor old muddle-headed Dora, so loyal, so anxious to help, so pleased and proud to think she was of assistance—and, alas, so completely unreliable.