По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

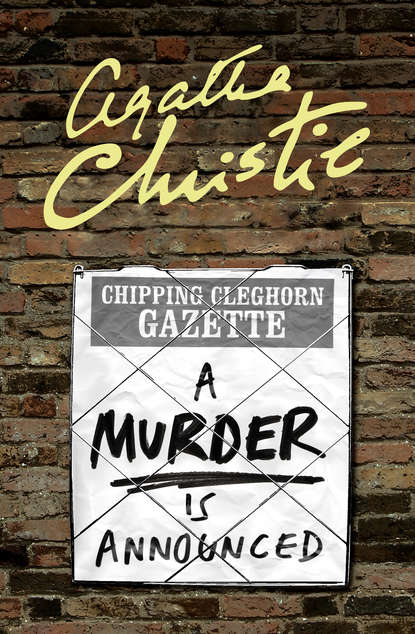

A Murder is Announced

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Daft,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe.

‘Yes, but what do you think it means?’

‘Means a drink, anyway,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe.

‘You think it’s a sort of invitation?’

‘We’ll find out what it means when we get there,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe. ‘Bad sherry, I expect. You’d better get off the grass, Murgatroyd. You’ve got your bedroom slippers on still. They’re soaked.’

‘Oh, dear.’ Miss Murgatroyd looked down ruefully at her feet. ‘How many eggs today?’

‘Seven. That damned hen’s still broody. I must get her into the coop.’

‘It’s a funny way of putting it, don’t you think?’ Amy Murgatroyd asked, reverting to the notice in the Gazette. Her voice was slightly wistful.

But her friend was made of sterner and more single-minded stuff. She was intent on dealing with recalcitrant poultry and no announcement in a paper, however enigmatic, could deflect her.

She squelched heavily through the mud and pounced upon a speckled hen. There was a loud and indignant squawking.

‘Give me ducks every time,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe. ‘Far less trouble …’

‘Oo, scrumptious!’ said Mrs Harmon across the breakfast table to her husband, the Rev. Julian Harmon, ‘there’s going to be a murder at Miss Blacklock’s.’

‘A murder?’ said her husband, slightly surprised. ‘When?’

‘This afternoon … at least, this evening. 6.30. Oh, bad luck, darling, you’ve got your preparations for confirmation then. It is a shame. And you do so love murders!’

‘I don’t really know what you’re talking about, Bunch.’

Mrs Harmon, the roundness of whose form and face had early led to the soubriquet of ‘Bunch’ being substituted for her baptismal name of Diana, handed the Gazette across the table.

‘There. All among the second-hand pianos, and the old teeth.’

‘What a very extraordinary announcement.’

‘Isn’t it?’ said Bunch happily. ‘You wouldn’t think that Miss Blacklock cared about murders and games and things, would you? I suppose it’s the young Simmonses put her up to it—though I should have thought Julia Simmons would find murders rather crude. Still, there it is, and I do think, darling, it’s a shame you can’t be there. Anyway, I’ll go and tell you all about it, though it’s rather wasted on me, because I don’t really like games that happen in the dark. They frighten me, and I do hope I shan’t have to be the one who’s murdered. If someone suddenly puts a hand on my shoulder and whispers, “You’re dead,” I know my heart will give such a big bump that perhaps it really might kill me! Do you think that’s likely?’

‘No, Bunch. I think you’re going to live to be an old, old woman—with me.’

‘And die on the same day and be buried in the same grave. That would be lovely.’

Bunch beamed from ear to ear at this agreeable prospect.

‘You seem very happy, Bunch?’ said her husband, smiling.

‘Who’d not be happy if they were me?’ demanded Bunch, rather confusedly. ‘With you and Susan and Edward, and all of you fond of me and not caring if I’m stupid … And the sun shining! And this lovely big house to live in!’

The Rev. Julian Harmon looked round the big bare dining-room and assented doubtfully.

‘Some people would think it was the last straw to have to live in this great rambling draughty place.’

‘Well, I like big rooms. All the nice smells from outside can get in and stay there. And you can be untidy and leave things about and they don’t clutter you.’

‘No labour-saving devices or central heating? It means a lot of work for you, Bunch.’

‘Oh, Julian, it doesn’t. I get up at half-past six and light the boiler and rush around like a steam engine, and by eight it’s all done. And I keep it nice, don’t I? With beeswax and polish and big jars of Autumn leaves. It’s not really harder to keep a big house clean than a small one. You go round with mops and things much quicker, because your behind isn’t always bumping into things like it is in a small room. And I like sleeping in a big cold room—it’s so cosy to snuggle down with just the tip of your nose telling you what it’s like up above. And whatever size of house you live in, you peel the same amount of potatoes and wash up the same amount of plates and all that. Think how nice it is for Edward and Susan to have a big empty room to play in where they can have railways and dolls’ tea-parties all over the floor and never have to put them away? And then it’s nice to have extra bits of the house that you can let people have to live in. Jimmy Symes and Johnnie Finch—they’d have had to live with their in-laws otherwise. And you know, Julian, it isn’t nice living with your in-laws. You’re devoted to Mother, but you wouldn’t really have liked to start our married life living with her and Father. And I shouldn’t have liked it, either. I’d have gone on feeling like a little girl.’

Julian smiled at her.

‘You’re rather like a little girl still, Bunch.’

Julian Harmon himself had clearly been a model designed by Nature for the age of sixty. He was still about twenty-five years short of achieving Nature’s purpose.

‘I know I’m stupid—’

‘You’re not stupid, Bunch. You’re very clever.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m not a bit intellectual. Though I do try … And I really love it when you talk to me about books and history and things. I think perhaps it wasn’t an awfully good idea to read aloud Gibbon to me in the evenings, because if it’s been a cold wind out, and it’s nice and hot by the fire, there’s something about Gibbon that does, rather, make you go to sleep.’

Julian laughed.

‘But I do love listening to you, Julian. Tell me the story again about the old vicar who preached about Ahasuerus.’

‘You know that by heart, Bunch.’

‘Just tell it me again. Please.’

Her husband complied.

‘It was old Scrymgour. Somebody looked into his church one day. He was leaning out of the pulpit and preaching fervently to a couple of old charwomen. He was shaking his finger at them and saying, “Aha! I know what you are thinking. You think that the Great Ahasuerus of the First Lesson was Artaxerxes the Second. But he wasn’t!” And then with enormous triumph, “He was Artaxerxes the Third.”’

It had never struck Julian Hermon as a particularly funny story himself, but it never failed to amuse Bunch.

Her clear laugh floated out.

‘The old pet!’ she exclaimed. ‘I think you’ll be exactly like that some day, Julian.’

Julian looked rather uneasy.

‘I know,’ he said with humility. ‘I do feel very strongly that I can’t always get the proper simple approach.’

‘I shouldn’t worry,’ said Bunch, rising and beginning to pile the breakfast plates on a tray. ‘Mrs Butt told me yesterday that Butt, who never went to church and used to be practically the local atheist, comes every Sunday now on purpose to hear you preach.’

She went on, with a very fair imitation of Mrs Butt’s super-refined voice:

‘“And Butt was saying only the other day, Madam, to Mr Timkins from Little Worsdale, that we’d got real culture here in Chipping Cleghorn. Not like Mr Goss, at Little Worsdale, who talks to the congregation as though they were children who hadn’t had any education. Real culture, Butt said, that’s what we’ve got. Our Vicar’s a highly educated gentleman—Oxford, not Milchester, and he gives us the full benefit of his education. All about the Romans and the Greeks he knows, and the Babylonians and the Assyrians, too. And even the Vicarage cat, Butt says, is called after an Assyrian king!” So there’s glory for you,’ finished Bunch triumphantly. ‘Goodness, I must get on with things or I shall never get done. Come along, Tiglath Pileser, you shall have the herring bones.’

Opening the door and holding it dexterously ajar with her foot, she shot through with the loaded tray, singing in a loud and not particularly tuneful voice, her own version of a sporting song.