По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

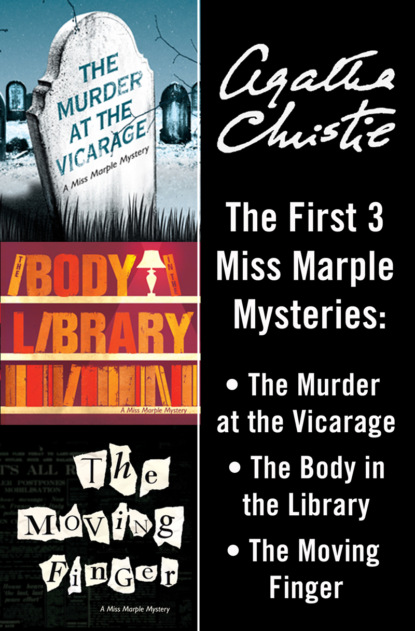

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lawrence sneered slightly.

‘Isn’t that a French idea? Reconstruction of the crime?’

‘My dear boy,’ said Colonel Melchett, ‘don’t take that tone with us. Are you aware that someone else has also confessed to committing the crime which you pretend to have committed?’

The effect of these words on Lawrence was painful and immediate.

‘S-s-omeone else?’ he stammered. ‘Who – who?’

‘Mrs Protheroe,’ said Colonel Melchett, watching him.

‘Absurd. She never did it. She couldn’t have. It’s impossible.’

Melchett interrupted him.

‘Strangely enough, we did not believe her story. Neither, I may say, do we believe yours. Dr Haydock says positively that the murder could not have been committed at the time you say it was.’

‘Dr Haydock says that?’

‘Yes, so, you see, you are cleared whether you like it or not. And now we want you to help us, to tell us exactly what occurred.’

Lawrence still hesitated.

‘You’re not deceiving me about – about Mrs Protheroe? You really don’t suspect her?’

‘On my word of honour,’ said Colonel Melchett.

Lawrence drew a deep breath.

‘I’ve been a fool,’ he said. ‘An absolute fool. How could I have thought for one minute that she did it –’

‘Suppose you tell us all about it?’ suggested the Chief Constable.

‘There’s not much to tell. I – I met Mrs Protheroe that afternoon –’ He paused.

‘We know all about that,’ said Melchett. ‘You may think that your feeling for Mrs Protheroe and hers for you was a dead secret, but in reality it was known and commented upon. In any case, everything is bound to come out now.’

‘Very well, then. I expect you are right. I had promised the Vicar here (he glanced at me) to – to go right away. I met Mrs Protheroe that evening in the studio at a quarter past six. I told her of what I had decided. She, too, agreed that it was the only thing to do. We – we said goodbye to each other.

‘We left the studio, and almost at once Dr Stone joined us. Anne managed to seem marvellously natural. I couldn’t do it. I went off with Stone to the Blue Boar and had a drink. Then I thought I’d go home, but when I got to the corner of this road, I changed my mind and decided to come along and see the Vicar. I felt I wanted someone to talk to about the matter.

‘At the door, the maid told me the Vicar was out, but would be in shortly, but that Colonel Protheroe was in the study waiting for him. Well, I didn’t like to go away again – looked as though I were shirking meeting him. So I said I’d wait too, and I went into the study.’

He stopped.

‘Well?’ said Colonel Melchett.

‘Protheroe was sitting at the writing table – just as you found him. I went up to him – touched him. He was dead. Then I looked down and saw the pistol lying on the floor beside him. I picked it up –and at once saw that it was my pistol.

‘That gave me a turn. My pistol! And then, straightaway I leaped to one conclusion. Anne must have bagged my pistol some time or other – meaning it for herself if she couldn’t bear things any longer. Perhaps she had had it with her today. After we parted in the village she must have come back here and – and – oh! I suppose I was mad to think of it. But that’s what I thought. I slipped the pistol in my pocket and came away. Just outside the Vicarage gate, I met the Vicar. He said something nice and normal about seeing Protheroe – suddenly I had a wild desire to laugh. His manner was so ordinary and everyday and there was I all strung up. I remember shouting out something absurd and seeing his face change. I was nearly off my head, I believe. I went walking – walking – at last I couldn’t bear it any longer. If Anne had done this ghastly thing, I was, at least, morally responsible. I went and gave myself up.’

There was a silence when he had finished. Then the Colonel said in a business-like voice:

‘I would like to ask just one or two questions. First, did you touch or move the body in any way?’

‘No, I didn’t touch it at all. One could see he was dead without touching him.’

‘Did you notice a note lying on the blotter half concealed by his body?’

‘No.’

‘Did you interfere in any way with the clock?’

‘I never touched the clock. I seem to remember a clock lying overturned on the table, but I never touched it.’

‘Now as to this pistol of yours, when did you last see it?’

Lawrence Redding reflected. ‘It’s hard to say exactly.’

‘Where do you keep it?’

‘Oh, in a litter of odds and ends in the sitting-room in my cottage. On one of the shelves of the bookcase.’

‘You left it lying about carelessly?’

‘Yes. I really didn’t think about it. It was just there.’

‘So that anyone who came to your cottage could have seen it?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you don’t remember when you last saw it?’

Lawrence drew his brows together in a frown of recollection.

‘I’m almost sure it was there the day before yesterday. I remember pushing it aside to get an old pipe. I think it was the day before yesterday – but it may have been the day before that.’

‘Who has been to your cottage lately?’

‘Oh! Crowds of people. Someone is always drifting in and out. I had a sort of tea party the day before yesterday. Lettice Protheroe, Dennis, and all their crowd. And then one or other of the old Pussies comes in now and again.’

‘Do you lock the cottage up when you go out?’

‘No; why on earth should I? I’ve nothing to steal. And no one does lock their house up round here.’

‘Who looks after your wants there?’

‘An old Mrs Archer comes in every morning to “do for me” as it’s called.’