По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

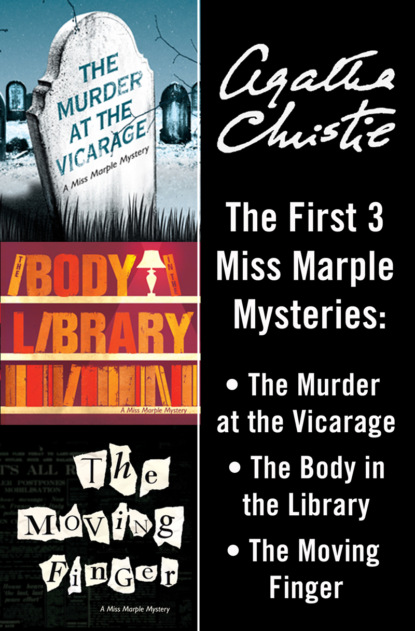

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He ought to, certainly,’ I agreed. ‘But the police are not satisfied with his story.’

‘But why should he say he’d done it if he hasn’t?’

That was a point on which I had no intention of enlightening Miss Cram. Instead I said rather vaguely:

‘I believe that in all prominent murder cases, the police receive numerous letters from people accusing themselves of the crime.’

Miss Cram’s reception of this piece of information was:

‘They must be chumps!’ in a tone of wonder and scorn.

‘Well,’ she said with a sigh, ‘I suppose I must be trotting along.’ She rose. ‘Mr Redding accusing himself of the murder will be a bit of news for Dr Stone.’

‘Is he interested?’ asked Griselda.

Miss Cram furrowed her brows perplexedly.

‘He’s a queer one. You never can tell with him. All wrapped up in the past. He’d a hundred times rather look at a nasty old bronze knife out of those humps of ground than he would see the knife Crippen cut up his wife with, supposing he had a chance to.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘I must confess I agree with him.’

Miss Cram’s eyes expressed incomprehension and slight contempt. Then, with reiterated goodbyes, she took her departure.

‘Not such a bad sort, really,’ said Griselda, as the door closed behind her. ‘Terribly common, of course, but one of those big, bouncing, good-humoured girls that you can’t dislike. I wonder what really brought her here?’

‘Curiosity.’

‘Yes, I suppose so. Now, Len, tell me all about it. I’m simply dying to hear.’

I sat down and recited faithfully all the happenings of the morning, Griselda interpolating the narrative with little exclamations of surprise and interest.

‘So it was Anne Lawrence was after all along! Not Lettice. How blind we’ve all been! That must have been what old Miss Marple was hinting at yesterday. Don’t you think so?’

‘Yes,’ I said, averting my eyes.

Mary entered.

‘There’s a couple of men here – come from a newspaper, so they say. Do you want to see them?’

‘No,’ I said, ‘certainly not. Refer them to Inspector Slack at the police station.’

Mary nodded and turned away.

‘And when you’ve got rid of them,’ I said, ‘come back here. There’s something I want to ask you.’

Mary nodded again.

It was some few minutes before she returned.

‘Had a job getting rid of them,’ she said. ‘Persistent. You never saw anything like it. Wouldn’t take no for an answer.’

‘I expect we shall be a good deal troubled with them,’ I said. ‘Now, Mary, what I want to ask you is this: Are you quite certain you didn’t hear the shot yesterday evening?’

‘The shot what killed him? No, of course I didn’t. If I had of done, I should have gone in to see what had happened.’

‘Yes, but –’ I was remembering Miss Marple’s statement that she had heard a shot ‘in the woods’. I changed the form of my question. ‘Did you hear any other shot – one down in the wood, for instance?’

‘Oh! That.’ The girl paused. ‘Yes, now I come to think of it, I believe I did. Not a lot of shots, just one. Queer sort of bang it was.’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘Now what time was that?’

‘Time?’

‘Yes, time.’

‘I couldn’t say, I’m sure. Well after tea-time. I do know that.’

‘Can’t you get a little nearer than that?’

‘No, I can’t. I’ve got my work to do, haven’t I? I can’t go on looking at clocks the whole time – and it wouldn’t be much good anyway – the alarm loses a good three-quarters every day, and what with putting it on and one thing and another, I’m never exactly sure what time it is.’

This perhaps explains why our meals are never punctual. They are sometimes too late and sometimes bewilderingly early.

‘Was it long before Mr Redding came?’

‘No, it wasn’t long. Ten minutes – a quarter of an hour – not longer than that.’

I nodded my head, satisfied.

‘Is that all?’ said Mary. ‘Because what I mean to say is, I’ve got the joint in the oven and the pudding boiling over as likely as not.’

‘That’s all right. You can go.’

She left the room, and I turned to Griselda.

‘Is it quite out of the question to induce Mary to say sir or ma’am?’

‘I have told her. She doesn’t remember. She’s just a raw girl, remember?’

‘I am perfectly aware of that,’ I said. ‘But raw things do not necessarily remain raw for ever. I feel a tinge of cooking might be induced in Mary.’

‘Well, I don’t agree with you,’ said Griselda. ‘You know how little we can afford to pay a servant. If once we got her smartened up at all, she’d leave. Naturally. And get higher wages. But as long as Mary can’t cook and has those awful manners – well, we’re safe, nobody else would have her.’

I perceived that my wife’s methods of housekeeping were not so entirely haphazard as I had imagined. A certain amount of reasoning underlay them. Whether it was worthwhile having a maid at the price of her not being able to cook, and having a habit of throwing dishes and remarks at one with the same disconcerting abruptness, was a debatable matter.

‘And anyway,’ continued Griselda, ‘you must make allowances for her manners being worse than usual just now. You can’t expect her to feel exactly sympathetic about Colonel Protheroe’s death when he jailed her young man.’

‘Did he jail her young man?’