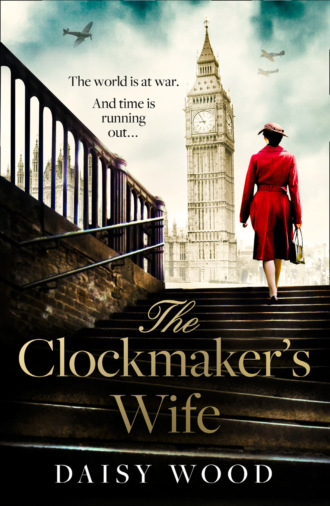

THE CLOCKMAKER’S WIFE

Daisy Wood

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2021

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2021

Cover design © Caroline Young, HarperCollinsPublishers 2021

Cover photographs © Joanna Czcogala/Trevillion Images (woman), Roy Bishop/Arcangel Images (steps), George W Johnson/Getty Images (Big Ben), Shutterstock.com (planes)

Daisy Wood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008402303

Ebook Edition © July 2021 ISBN: 9780008402310

Version: 2021-02-22

Dedication

To Philip, with love and gratitude

Author’s note

Big Ben – as the Great Clock at the Palace of Westminster has come to be known – is recognised around the world, a landmark that draws tourists like a magnet and tells Londoners they’re home. During the Second World War, however, the clock held an even greater significance. In prison camps, cellars, attics and back rooms all over Nazi-occupied Europe, people secretly tuned into wireless broadcasts from the BBC – and for most of the war, the chimes of Big Ben were used to announce the nine o’clock evening news. People everywhere were encouraged to pray for peace as they listened, and this sacred moment was known as the Silent Minute. The great bell represented freedom and better times to come; as long as it tolled, at least one country resisted oppression.

The Clockmaker’s Wife is a work of fiction. As far as we know, there was no conspiracy to destroy Big Ben on New Year’s Eve in 1940; certainly, no evidence has ever been found. The Houses of Parliament had been bombed in September of that year and were to be more seriously damaged in May 1941, when the Commons Chamber was destroyed by incendiaries, but these episodes were incidental rather than targeted. Yet such a plan isn’t inconceivable. St Paul’s Cathedral had only been saved by a miracle a couple of nights before, when over a hundred thousand bombs were dropped on the ancient City of London. The Palace of Westminster was similarly vulnerable, and the loss of such a beacon of hope as the clock tower would have been a terrible blow to morale.

Despite this imaginative leap, I have tried to ground the plot and setting of my novel in historical reality. When I began dreaming up the story, renovation work to the clock tower was already under way and a visit in person was impossible. Yet I was lucky enough to experience the next best thing: a talk at the Houses of Parliament by one of the guides, Catherine Moss. She and her colleague, Lindsay Schusman, know all there is to know about Big Ben and I’m extremely grateful to them both for their help, so generously given. At the time of writing, these renovations are still some way from completion, but the results will surely be spectacular. I’ve come to think of Big Ben as an old friend, and a trip up the clock tower is top of my wish list when the world returns to some kind of normality.

I wrote much of this novel during months of lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic. It’s been a strange time, and one can’t help noting the similarities and contrasts with wartime Britain as we currently battle a more insidious, invisible enemy. Researching London during the Blitz has left me overwhelmed by the extraordinary courage of so many ‘ordinary’ people, men and women just like Nell and Arthur, and in awe of the sacrifices they made to ensure the freedom of generations to come. I couldn’t help thinking of my own grandmother, the original Daisy Wood, who lost her brother during the First World War and brought up her daughter, my mother, during the Second. How I wish I could talk to her now!

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s note

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

London, April 1939

‘Not much further,’ Arthur calls down to Nell, who is labouring up the stone spiral staircase behind him. She’s wearing new shoes that have rubbed a blister on the back of her heel, and it’s been a long day, but she knows how much this visit means to Arthur so she perseveres. He’s rightly proud of his work, maintaining the clocks at the Palace of Westminster, and she knows it’s taken some negotiation with the Keeper of the Clock for permission to show her the greatest one of all: the huge turret clock that Nell in her ignorance used to call Big Ben. Arthur had quickly put her right. Big Ben, she knows now, refers to the vast bell that strikes the hours, rather than the clock itself.

She’s learned a lot about this clock since meeting Arthur – or rather, she would have learned a lot, if she weren’t so distracted by his steady brown eyes, gazing intently into hers, by the hollows under his cheekbones and the bluish stubble around his jaw, by that mysterious male presence that takes the words out of her mouth and the breath from her lungs. Sometimes they can talk for hours and it seems as though they’ve known each other for years; more often, she simply stares at the way his curly hair springs up from his forehead or the curve of his beautiful mouth and wonders how long she’ll have to wait until he’s kissing her. She thinks about him all the time. He’s on her mind from first thing in the morning until last thing at night, and people have begun to notice. The headmistress has had to have sharp words with Nell about leaving her personal life at home.

So now she smiles back at Arthur and tells him she’s fine, slips off her shoes and limps after him in her stockinged feet. First, he takes her to the clockmakers’ room, where their tools and equipment are stored. Technically, Arthur is employed by Saunders, an external company of clock and watchmakers, rather than the Palace of Westminster. Yet the Palace is where he and his colleagues spend most of their time, winding, adjusting and maintaining the hundreds of clocks that mark the hours as Parliament goes about its business. And also when it’s in recess, of course. There are two other clockmakers apart from Arthur: Ralph Watkinson (whom he likes) and Bill Talbot (whom he doesn’t).

Their room is low-ceilinged, with short windows beneath the overhanging dials above. Arthur shows her the workbench where his tools are neatly arranged, ready for the morning.

‘Sure I’m not boring you?’ he asks, and she hastens to reassure him. ‘You are a dear girl to be so interested,’ he says, blushing a little, and his flush deepens when she catches sight of her photograph in pride of place on the shelf, self-conscious in pearls and an evening gown. Dropping his eyes, he exclaims over her lack of shoes and binds her bleeding heel with his handkerchief, taking such care that she melts under his touch. She’s longing for him to kiss her when he straightens up, but instead he unlocks the door to an inspection hatch and shows her the weights running up and down the central shaft of the tower. She can just make them out, far below in the gloom. There are three weights, he explains, controlling the three gear trains by which the Great Clock operates: the striking train driving the hammer which drops against Big Ben, the chiming train that controls the quarter bells, and the going train that powers the clock hands. The striking and chiming trains are wound back up by electric motor when they reach the bottom of the shaft, Arthur says, but the going train has to be wound by hand, three times a week.

‘Goodness.’ Nell could listen to him talk all evening – although, to be perfectly honest, she pays more attention to his dimples than she does to the gear trains. He wants to share his great passion with her, and she knows this is a significant moment. Who would have thought the workings of a turret clock could be so romantic?

Arthur takes Nell’s hand and leads her through the gallery behind the four huge dials. Dusk is falling and the light bulbs behind each clock face are blazing; people on the ground over three hundred feet below will be looking up to check the time as they hurry to meet friends or lovers, or head home after work. Nell peers up at the milky glass. She can’t see through to the Roman numerals on the other side, but Arthur tells her they are over two feet high, and the minute hand is fourteen feet long. The scale is awe-inspiring.

After this excitement, they go up another flight of stairs to see the clock mechanism itself, an intricate arrangement of wheels, cogs, levers and ratchets laid out on a flatbed frame. The machinery was made in Victorian times; a work of art, combining beauty and precision. Nell’s face is beginning to ache from all the smiling when a tremendous racket starts above their heads, the smaller bells ringing out the quarter hour. She and Arthur put their hands over their ears, beaming at each other. I do love you, she thinks, and wonders when she’ll find the courage to tell him. Probably not tonight. He seems in a strange mood: preoccupied, distracted, distant. He’s probably tired after a day’s work, and of course he’s worried about the current state of affairs on the Continent, along with everyone else. They had a long conversation about that alarming little man Hitler the other night. Arthur’s parents are German but they moved to England before he was born – which, as things have turned out, was just as well.

At last the Westminster Chimes die away and the fly fans high up in the room come to a noisy, clattering halt.

Falling well and truly under the spell of this extraordinary place, Nell hurries after Arthur, up another flight of stairs to the belfry where Big Ben hangs in state; a caged beast behind an iron fence, with the quarter bells arranged around him like planets orbiting the sun. She leans over the wire-mesh barrier to lay her hand against his great scarred side and stand for a moment, drinking in the quiet atmosphere. Arthur, however, is in a hurry. He wants to show her the Ayrton light, which is lit when either House of Parliament is sitting after dark. Frowning, he looks at his watch and hustles her towards the open metal staircase as though they’re late for an appointment.

‘Hope you don’t mind heights,’ he says, bounding up the first few steps without looking back. Nell follows, trying to ignore the open iron latticework beneath her feet and the wind that steals under her crimson coat, freezing her stockinged legs. When they climb out onto the balcony running around the lantern, she’s glad of Arthur’s hand to hold, and gladder still when he puts his arm around her shoulders and draws her close, inhaling the scent of her hair, which she rinsed in lavender water, just in case this situation might arise. They gaze out over London, quiet in the deep blue haze of evening. The dolphin streetlamps along the Embankment are shining like strings of pearls as the sinking sun outlines fleecy clouds in pink and gold; the lights of barges heading towards the docks gleam like fireflies on the water. Nell can see as far as Tower Bridge in one direction and Lambeth Bridge in another, spot the golden angel glinting on the memorial outside Buckingham Palace, and glimpse Nelson standing proud on his column at Trafalgar Square. The cars crossing Westminster Bridge look like Matchbox toys from this height, and the roar of the traffic is muted. She and Arthur are completely alone, with this extraordinary scene laid out before them.

The sight of his serious face casts a shadow over her happiness. Now, at last, she understands why he’s brought her here. ‘War’s coming, isn’t it?’ she asks, so quietly that she might be talking to herself. ‘You want me to see the city before everything changes.’

‘I think it’s inevitable, sadly,’ he replies. ‘And sooner rather than later.’

Now a terrible fear clutches her heart. ‘Please don’t tell me you’re leaving. Are you about to say goodbye?’ Ridiculous tears spring to her eyes; she’ll blame them on the wind. He looks away, biting his lip. ‘Don’t go,’ she begs, abandoning all trace of dignity. ‘You needn’t, Arthur, not till they send for you. Let other men play the hero.’

He takes her hand. ‘I have brought you here for a reason, but it’s not that,’ he says, gazing into her eyes. ‘We haven’t known each other long, dearest Nell, but it’s been long enough for me to have fallen head over heels in love with you. Let’s make a home and grow old together. We might never be rich but I swear, I’ll move heaven and earth to make you happy. Oh, damn, I meant to do this properly.’ He starts patting his pockets. ‘Where is it? I’m sure … Ah, yes, here we are.’

He produces a small black box and, sinking to one knee, opens and offers it up to her. ‘Nell Roberts, I’m only a humble clockmaker, but would you do me the honour of becoming my wife?’ When she doesn’t reply instantly he repeats, with the merest hint of desperation, ‘Will you marry me, darling girl?’

Laughing and crying at the same time, lost for even the simplest of words, Nell helps Arthur to his feet. Her expression is all the answer he needs. He takes the ring from its velvet bed and slips it on her finger and then, at last, he kisses her; the most magical kiss there has ever been or will be again. At that very moment the world explodes as the bells beneath their feet begin to chime, followed by a few seconds of silence before the mighty hammer drops and Big Ben rings out in celebration. Arthur’s timing is impeccable – naturally.

Chapter One

London, November 1940

Nell looked at the clock for what felt like the hundredth time. Arthur had never been home as late as this before. It was almost eight o’clock. What on earth could have happened? The bombers had been coming earlier and earlier – almost as soon as it was dark, sometimes – but so far the night had been quiet and the alert hadn’t sounded, so he couldn’t have been caught up in a raid. She went to the front room and pulled aside the blackout blind to look out. It was dark and quiet, the moon only a fingernail paring and a solitary searchlight roaming the clouds. She could make out the bulk of a couple of barrage balloons, bobbing and swaying from their moorings like vast tethered animals. The street was empty, apart from a couple of ARP wardens standing on the corner, playing their torches over the house that had been bombed a couple of months before. Rumour had it that a tramp had moved in, though no one had actually seen him. Nell dropped the blind; those men could spot a chink of light at fifty paces.

Sighing, she walked back down the hall, edging past the pram. The liver she had queued an hour to buy had been drying out in the oven since half past six; Arthur would probably break a tooth if he tried to eat it now. Upstairs, Alice gave a drowsy, half-hearted wail. Nell stood for a moment to listen, holding her breath, but the baby seemed to have settled down so she carried on to the kitchen, to find the largest mouse she had ever seen – could it even have been a rat? – running across the floor. She couldn’t help screaming, and then of course Alice woke up and screamed too, and the house was in uproar when Arthur’s key turned in the lock.

‘Arthur! Where have you been?’ she cried, clutching her sobbing baby, on the verge of tears herself. ‘I was so worried! Supper’s ruined and we’ve nothing else to eat except a tin of corned beef that I was saving for the weekend. I was trying so hard to make everything lovely but the house is infested with vermin and it’s all too ghastly for words.’

‘You poor thing. Here, give Alice to me.’ Gently, Arthur scooped up the baby and walked her up and down, humming under his breath. Alice buried her damp face in his shoulder, hiccupped a couple of times and fell asleep.

‘But you haven’t even had time to hang up your things.’ Full of remorse, Nell took off his hat while he shrugged his arms out of his coat so she could relieve him of that, too. His clothes were cold and damp, and smelt of soot. ‘Oh, I’m the worst wife in the world!’ she burst out. ‘I’m meant to change and put on fresh lipstick before you come home and here I am, nagging like some awful harpy. Can you forgive me?’

He smiled. ‘As long as you can forgive me for being so late. And, darling, I wouldn’t mind if you came to the door in sackcloth and ashes.’ He kissed the top of her head. ‘Why don’t you make a pot of tea while I put Alice back in her cot and then we can decide what to do about supper and vermin.’

She shouldn’t have mentioned the mouse, Nell realised, putting the kettle on to boil. Arthur might use that against her in their ongoing debate – it wasn’t an argument, not yet – that was becoming increasingly heated as the bombing continued.

‘So how was your day?’ she asked him brightly when he came back downstairs. ‘Is Mr Watkinson back at work yet?’

‘Sadly not.’ He took a sip of tea and gave a small involuntary shudder.

‘Sorry. We’re out of fresh milk so I had to use powdered.’ What a terrible housewife she was.

‘At least it’s hot,’ he said gamely. ‘Well, warm.’

‘Warmish,’ Nell said, and they laughed.

‘Talbot’s been up to his usual tricks,’ Arthur went on. ‘I couldn’t leave without checking the work he can’t be bothered to finish. He’s getting more slapdash than ever and he’s not training the lad properly, either. Sam’s picking up all sorts of bad habits. And when I point out where Talbot’s gone wrong, he goes off at the deep end. He can’t bear any sort of criticism. We need Watkinson to keep the peace. Still, enough of my woes. What’s this about the house being infested?’

‘I thought I saw a mouse,’ Nell replied, ‘but it was probably just my imagination.’ She retrieved Arthur’s plate from the oven and placed it in front of him. ‘Now, do your best. I’ve eaten already.’ Only potatoes and a slice of bread and marge, but she wasn’t particularly hungry.

‘I’m absolutely ravenous.’ And he must have been, because he managed to polish off the liver and most of the potatoes that had collapsed into a heap of grey mush. They had learned to eat supper quickly, before the air-raid siren inevitably sent them hurrying to the shelter.

‘I’ve got a surprise for you,’ Arthur said, when he had forced down the last mouthful. ‘Close your eyes and hold out your hands.’

He put something round and smooth in her cupped palms. She gasped when she saw it. ‘An orange! Where on earth did you find that?’

‘It fell off the back of a lorry.’ He grinned, delighted by her reaction.

Nell dug her fingernail into the fruit’s waxy peel and inhaled the sharp citrus scent. It had been months since she’d seen an orange in the shops, let alone held one. The skin was already wrinkled and the fruit probably wouldn’t last till Christmas, more than a month away. She would keep it till the weekend, she decided, and share it with Alice and Arthur after tea. Maybe Alice could eat her segments in the bath, so as not to make a mess of her clothes. They were running low on soap powder and even a bib took ages to dry at this time of year.

‘I want you to eat it all yourself,’ Arthur said, as if reading her thoughts. He put his plate in the sink, scooped up her hair and kissed his favourite spot at the nape of her neck. ‘You’re looking rather run down these days, my darling. You know how I worry.’

She did indeed. He went on, ‘Thought any more about what we discussed the other day?’

‘I’m not going to change my mind,’ she replied. ‘We belong together, Arthur – that’s what we’ve always said. Whatever this war throws at us, we’ll face it side by side.’

He sat down again, his face serious. ‘There’s Alice to think about now. It’s not fair to put her through all this, not when you could both be safe in the country.’

Nell stuck out her jaw. ‘If the Queen won’t leave London, I don’t see why I should.’

‘But the Queen lives in Buckingham Palace, not a terraced house in Vauxhall.’

Nell sighed. ‘Let’s not go over this again, not when we’re both so tired. We’re just going around in circles. We’ll talk about it at the weekend, I promise.’ She glanced at the clock. ‘Nearly time for the news.’

They went through to the front room and Nell switched on the wireless. Now there was an added incentive to tune in: since the previous Sunday, Armistice Day, the pips introducing the nine o’clock news had been replaced by the chimes of Big Ben. Arthur had been so proud. People all over the country would be listening to that solemn sound, united in love for their country. She smiled at him across the hearth as the notes died away, but he was deep in thought and didn’t notice. Sighing again, she turned her attention to the world beyond their small terraced house. There was encouraging news from North Africa, apparently: thousands of Italian soldiers were surrendering in Egypt and British troops had captured some fort or other in Libya.

She yawned, her eyes drooping. The siren hadn’t sounded yet and it was getting late; perhaps tonight they would be lucky. ‘Please, God,’ she prayed to herself, ‘let us not have to go to the shelter.’ It was a selfish request, given the suffering some people had to endure, but she’d come to loathe the Anderson with a passion. The shelter stood in the garden of their neighbours, Mr and Mrs Blackwell, who had generously offered to share it when the raids had started, what seemed like a lifetime ago.

‘We wouldn’t hear of you going to a public shelter, Mrs Spelman,’ Mrs Blackwell had said. ‘Neighbours have to stick together these days.’

None of them had had any idea they would be spending so much time together, but London had been bombed relentlessly since that first week of September. Night after night, Nell had stumbled along the icy garden path, Alice clutched to her chest in a cocoon of blankets. Four slippery moss-covered steps led down into the shelter’s chilly interior, where spiders and possibly rats lurked in every corner, and a frog had once hopped onto her foot; it had squatted there for a moment, staring at her in the light of a candle with its wet black eyes. Nell had always hated to be shut up in any confined space, let alone one that smelt of damp, mouse droppings and worse. She knew Alice felt the same. Most of the time, her daughter was an undemanding baby, but her small body would start to tense as soon as she caught sight of the shelter’s forbidding entrance.