По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

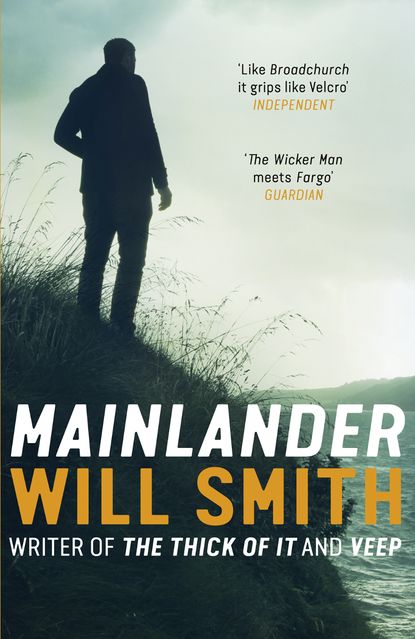

Mainlander

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Fine. He’s Corsican. You win. Point is, I trust the guy.’

Emma started picking her clothes off the floor. ‘Colin knows too.’

‘What?’

‘About us.’

‘Fucking hell! Why are you telling me this now?’

‘He only knows about the first time.’

Rob threw his head back. ‘Oh, Jesus, you nearly gave me a heart attack.’

‘Unlike Christophe, he’s very much an unlocked safe. Should make tomorrow interesting.’

‘Tomorrow?’

‘We’re coming for lunch.’

‘Are you? Sally never tells me anything.’

‘Sorry – you annoyed me about Christophe.’

‘It’s fine. Look at us, sniping like an old married couple.’

‘That’s not funny.’

‘I take it back. Are we okay?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I’d better get to work.’

‘Me too.’

Thinking that they might have spent the day together, Emma had called in sick immediately after confirming her rendezvous with Rob. An empty day now yawned before her. The weather was fair but she couldn’t face a walk. There was the risk of bumping into someone who knew someone from work and, in any case, she was dressed in her Midland Bank navy skirt and jacket, and court shoes. She set off driving round the Island, on the same roads, past the same houses, with the same faces at the same windows and the same shrubs in the same gardens. Every corner, every street lamp, every tree-shrouded lane was primed to trigger a memory. She felt as if she was driving through her own theme park.

She passed her parents’ St Clement’s beachfront house where she’d spent an awkward New Year following the announcement that her first term at Birmingham University was to be her last, and where Colin had written ‘Marry me’ in seashells outside her bedroom window on the first Christmas Day of their relationship.

Further along the coast road was the flat at La Rocque that she’d rented during the years of idle temping and dating, years of confusion and anger. There were natural laws in the universe that she had never imagined could be defied, and one of them was that she would marry sooner and better than Sally.

Gorey Castle was where Sally, sprawled against the outer battlements after a pub crawl on the last day of school, had told her she didn’t care about her exam results and had decided to turn down her university place: she wanted to be Mrs Rob de la Haye. It was also where Emma had first kissed Rob after they had rolled down the castle green, a sweeping slope edging the castle’s northern wall.

St Catherine’s Breakwater was a compound memory: multiple family walks in the rain, disappointing her father with her lack of enthusiasm for sailing, her younger brother Rory nearly falling off the edge during a tantrum, Colin boring her with his superior knowledge of the history of the breakwater.

As she drove up the east coast she remembered sitting alone at White Rock, bereft and broken after fulfilling her duties as Sally’s chief bridesmaid. She had been convinced that Sally was trying maliciously to emphasise her recent weight gain with the cut of the dress. At the end of the evening a drunken Sally had told Emma that she knew how hard it must have been to watch her and Rob walk down the aisle, but that she, too, would soon find her prince. Emma had played it cool, denying it was even an issue, while struggling to understand why it still was and why she was maintaining a friendship that served only to undermine her confidence and self-esteem. As she had watched the sun come up that morning, disappointed that its sickly rays still left her shivering under her car blanket, she had known she had to leave again.

On skirting the top of Bouley Bay she was reminded of Colin, and how on his first visit he had eulogised about how the purple pebbles matched the heather on the cliffs then wondered why she could ever want to leave such a place. She had come back to work for the summer to earn some cash before she set off on her TEFL travels. As their love grew and his stay extended from July to August, his enthusiasm made Emma see the Island in a new light and her travel plans receded. When the job at the school had come up in September, she had allowed herself to be swept up in his sense of Providence. Now she resented Colin for having cheated her out of other, possibly better, options. She could have been off this rock and married to an architect in New Zealand, sending round-robin Christmas letters detailing their idyllic life spent flitting between their beachfront mansion and thousand-acre farm.

Nearing the brown-brackened outcrops that loomed over Bonne Nuit, she realised that she was halfway round the Island. She was literally going round in a circle. She turned into the centre, determined to find an unfamiliar road. She veered left down a lane, remembered it led to her cousin Yvonne’s house, so took the next right, then another left and a right, all along lanes that she knew by sight if not by name. She took three straight lefts in a row, then discovered she had doubled back on herself and went into a frenzy of random turns, speeding as fast as she dared, pushing herself to near panic as she imagined the hedgerows folding over and swallowing her. She came to a crossroads. Straight ahead lay the Carrefour Selous, another crossroads at the middle of the central parish of St Lawrence. The right cut across to the top of St Peter’s Valley and the airport, dense copses lining the slow curve up to a plateau leading to the broad beaches of the west coast. A pleasant drive but one she’d made many times before. The left led back towards St Catherine’s and Rozel. She rested her chin on the steering wheel and a fugue descended, until an estate car stopped behind her and beeped. She pulled out quickly to the left, then noticed a smaller road just off it that led up a steep incline. To make it she had to swing on to the other side of the road, which caused an oncoming van to brake hard and blare its horn, but she had found her Holy Grail: she did not know where this road led. Her mood lifted, along with the land’s elevation, as the lane banked left and right.

She turned on the radio for a further boost but the nimble-fingered riff of Dire Straits’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ conjured a heart-tugging combination of jauntiness and despair. She turned the dial blindly, desperate for another song, one she hadn’t listened to endlessly as part of the compilation tape Bounce Back that she’d made around the time of Rob and Sally’s wedding. As she flicked between stations, she laughed at her misplaced fury with the station programmers. They hadn’t chosen to mock her with their selections. There was no conspiracy: this was the Island getting on top of her.

As the road rose she found a French station, which was accessible from various points on the Island. The song that was playing was the one she had chosen as the climax of that tape, a song as high in the air as ‘Romeo and Juliet’ was down on the floor.

Baby look at me,

And tell me what you see,

You ain’t seen the best of me yet,

Give me time I’ll make you forget the rest.

For some reason it unlocked within her a deep-hidden joy. She slapped up the volume and jigged in her seat, beeping her horn in time with the music, partly out of the need to warn any oncoming drivers of her presence as she rounded fern-laden corners, and partly out of an unexpected frenzy of optimism that could not be held back. As she sang along, ‘Fame! I’m going to live for ever’, she started to believe it, only a kernel of her feeling ridiculous, but that was part of her revelry: the ridiculous was far more fun than moroseness. Rob was just something she was working out of her system. She’d needed to go back to him to grasp that she didn’t really want him. Their affair was benign, a boon to her marriage as it would help her see the good in the husband with whom she lived on a beautiful island. She would not be drowned by the past. She would spring on top of it, laughing as it drained away. She stopped the car, her elation snatched away, as if a magician had pulled off a tablecloth leaving everything on it in its place.

She had driven this lane before. She must have. There in front of her was the farmhouse that Rob and Sally were having renovated. The same farmhouse that Rob had promised her when she was seventeen. Sally had taken her round the empty shell at a celebration barbecue following the successful purchase, pleading with Rob to replace an oak on the front lawn with a circular drive and a fountain, and expounding on the dilemma of deciding between a swimming-pool or a tennis court or both, but then having a limited garden space. Emma had been inclined to make sure she was not around for the work’s completion.

Builders were plodding around the house now: it was coming together. Emma leant her head against the car window, crushed by the epiphany that it wasn’t just the ghosts of the past that she had to wrestle and evade but the ghosts of the future. She could fool herself no longer. She had to leave, this time for good.

As she trudged up the stairs to the flat, with nothing to look forward to except sitting in the tainted glare of framed wedding photos, wondering if she’d ever smile like that again, Mrs Le Boutillier’s door opened. Emma’s mood deflated further.

‘Hello, Mrs Bygate, not at work today?’

‘No.’

‘Have you got that bug that’s going round?’

‘I think I probably have, so best keep back. I don’t want to give it to you.’

‘Very thoughtful of you – got to be careful at my age.’

Emma turned to put her key in the lock.

‘Oh, silly me, I’ve got this for you – you must have just missed him,’ Mrs Le Boutillier went on.

‘Colin?’ replied Emma, confused.

‘No, the boy. He had a letter for your husband. I said I’d make sure he got it. Things get awfully messed up in the pigeon-holes. Not everyone in this block takes as much care as I do, making sure the right letters go in the right places.’ She held up an envelope with ‘Mr Bygate’ handwritten in the centre.

‘Right, thanks.’ Emma tried not to sigh, but was weighed down by yet further proof that any interaction with her neighbour took at least five times longer than she might have predicted.

‘He was ever so helpful. I’d just got back from the market and he helped me in with my trolley. I offered him a cup of tea to say thank you but he said he was in a rush. Maybe I put him off, talking too much. That’s the thing when you live alone. If you get the chance to talk you probably do it too much …’

‘Right. I’ll make sure Colin gets it. Did he say who he was?’

‘He said he was a pupil.’

‘He should be at school then.’