По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

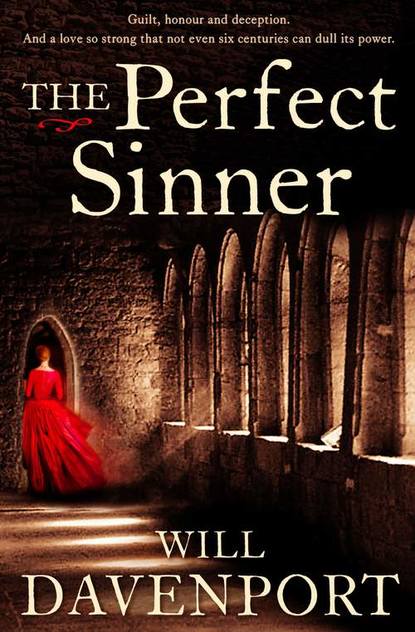

The Perfect Sinner

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I have been trying to make up for my second sin, you see. It took place in war and was a sin of omission. There was an act I failed to prevent. War has battered into me the slow realisation that it is man’s most natural state, a base business painted with glory only for disguise, but this act was the basest of its parts. I will speak out now as I should have spoken then. Our war with France has lasted all my adult life and now at last I know the shape of what I want to say. For an entire year I have been struggling for the right words. Now she came to me and flamed up there in the December sun. Elizabeth, a creature of pure light, gave me my opening line.

‘Old men who stay behind,’ she said, ‘old men who stay behind, do not inflame the young with words of war.’

Perhaps it came from inside me and not from her at all, but I don’t think so.

There are days which lie in ambush for you from the moment you are born. I had thought it was a day of endings, the dedication of my chapel, the setting in stone of the knowledge that came too late, my plea for forgiveness. Instead it was the very opposite, and before this winter day was finished I was to meet a man who would make me look at it all afresh.

As I stared up above the altar, Elizabeth slipped away from where she had stood smiling in the window and there was the Madonna Maria Virgine in her place, no less fine than she ought to be, but a picture on flat glass and no more than that. I fought down my keen regret because one should never feel regret at the sight of the Madonna, and there was some comfort to be taken. Elizabeth had seemed serene and the Madonna had let her share her space. She could be saved.

When Elizabeth died thirteen years ago, I had Hugh’s tomb in the Abbey opened and laid her next to him and there they lie, the two Despensers, just as if she had never been Elizabeth de Bryan, just as if two of my sins had never taken place. As if I had never been. It was not because I thought she loved him more than me. Indeed, I knew that could not possibly be the case. We had our years together, Elizabeth and I, and though they started later than they should have done, they were as sweet a time as I could ever have hoped for. Together, we had a natural harmony in everything we did, and our marriage felt to me like a long-delayed arrival home. It was just that in the Abbey, in the immediate sight of God, there was sin to consider and it seemed more proper that she should lie there with Hugh. When death comes for me they will put me close by, just across the aisle, in a tomb to match hers so that I will be but a hand-clasp away.

Hugh Despenser, you see, was the bravest and most admirable of men and he had to steel himself, against his natural inclination, to act that way, which makes my sins all the greater because two of them were against him. We first fought side by side a quarter of a century ago at the crossing of the Somme. He won the day for us at Blanchetaque, struggling through the water to beat the enemy off the far bank. He saved an entire English army that day with heroism that took your breath away and should have taken his.

Bad memories are the hardest rock and stand out more and more as the softer stuff gets washed away. What happened two days later in that August of 1346 ranks among the worst. We were across that bloody valley and they were coming up at us in numbers you could not believe. It was a typical late summer evening and, with the low sun behind us, they stood out so clearly, every detail of their equipment and their weapons, the straps and the steel, as fine and precise as a painting. In the glare they could not see how thin we were in our tired lines. We were dark reapers against the sun and we scythed them down until we were astonished by the slaughter and unsure if they would ever stop.

My post was by the King up on the hill, behind in his final reserve, and my duty was to watch, which is the hardest thing. They came in ranks a hundred soldiers wide, pushed forward by the weight of thousands more behind. Those behind had no clear view until those before them fell. Only then could they see that they were already as good as dead, invincible certainty draining into despair in the very last yards of their advance.

My second sin is coming with the smell of sulphur on its breath.

This tale will not allow the absence of its villain for a line longer, and there’s a pity. He has to come into it now. Sir John Molyns. Molyns the robber, Molyns the murderer. The King had hunted Molyns for his destructive violence. Now he was valued for that same quality. Now he was restored and there he was just ahead of me, down there in our line, about to commit a terrible act, and I should have prevented him from doing it. The King gave me the power to stop him and I chose not to use it. That was my second great sin.

My hands and my arms were shaking with exhaustion, holding the butt of the pole, and the wind got up again, whipping the King’s long standard, the Dragon banner of Wessex, as it billowed over my head. I was groaning from the concentrated effort it took to hold that standard upright and immobile and I knew how much it mattered. The flag, tugging at me in the gusts, was the weathercock of the battle, the final symbol. You could see the men snatch glances behind for the evidence that the Royal Will did not waver, that the Royal Person was resolute, sharing their own danger. The upright immobility of that standard was the proof. All very fine, but chivalry died that day.

There, in the torn and bloody earth of Crécy, chivalry died and perhaps I could have saved it.

A drizzle of holy water across my cheek pulled me back from that past, back to my new Chantry. In this other folded valley, a mile inland from the marching waves of Start Bay, I was pretending to kneel down. I was the sole member of the congregation in my own brand-new chapel, and there was nobody else here bar the priest to spot that my backside was still supported by the edge of the pew and my knees were a hand-span short of resting on the hassock. If the priest had noticed, he would have said nothing. William Batokewaye knew what a beating those knees had taken in the service of the King, after all, he’d been there for much of it.

A fine mist of sawdust still filtered down from the roof’s new-cut beams, filling the air with a spray of stained-glass sunlight. The pews smelt of sap and the stone itself showed the fresh face of sliced cheese. It was the forty-fifth year of the reign of his Royal Majesty, King Edward the Third and it should have been a red-letter day.

I watched William stumping up the aisle towards the altar as if he were attacking in the front rank of God’s army. He had always been a good man in a tight corner. Within a year of losing his sword-arm to a Frenchman’s axe, the stump barely healed, he had learnt a left-handed flick of the wrist which reaped soldiers like barley. These days, his only weapon was the holy water, but that same left wrist flicked back and forth to spread eternal life just as he had once spread death.

I was still in my reverie, half nightmare, half myth, embellished over years of remembering until it shone with the untrustworthy precision of a jewel from the devil’s diadem. I was remembering that moment in August of 1346 when three horses, lashed together, thundered at us through the piles of the dead. Then that rain of water arced across my face and shocked me out of my trance.

‘Wake up,’ rasped the priest, glancing back at me. ‘This is all for you, so you might at least pay attention.’

For a moment, I wasn’t quite sure which was then and which was now because that voice belonged to both times, but in those days the priest had all his limbs and I had a clear conscience.

He stopped his chanting and his spraying, stared around him at all the gilt and the fresh paint and the no-expense-spared glory of the place. He pulled an oddly irreligious face.

‘It’s done,’ he said, swivelling to stare at me. ‘Blessed and dedicated. Are you happy now? You should be.’

I could only look at him, and perhaps he saw something in my eyes because he put his thurible down, reached out to take me by the arm and helped me clamber to my feet.

‘Come on. Outside,’ he said.

There was complete and unexpected peace in the courtyard. It was warm for December. I had expected the usual scraping and hammering of the masons working on the rest of my buildings, forgetting I had sent them all off to work in the quarry to guarantee silence for the consecration. There was no sign of human life or so I thought for a moment. Then a tiny movement up above caught my eye. They are as keen as they ever were, my eyes, and I depend on them all the more now that my body is no longer quite so agile. It has always been second nature to watch for that betraying movement in the undergrowth that might save you from an ambush.

There was a man up there on the high ground, the hill which overlooks my village and my Chantry, and I saw him stand up. He didn’t look familiar.

‘Tell me what’s going on,’ William demanded and distracted me. We sat down side by side on a bench, the priest folding his robe under him. He looked at the mud drying on the back of it.

‘I wish you’d put drains down the street,’ he said. ‘I went right over on my arse.’

They like it the way it is, the villagers.’ I replied. ‘It’s always been like that. You know that better than me. This was your place before you ever brought me here. I didn’t even know about it until you told me.’

‘Slapton, eh?’ said the priest, looking around him, ‘It’s thirty years since I lived here last. There’s no kin of mine left here now and I feel almost a stranger. I went away to see the wider world and I’ve learnt to like a drier path to walk on. My grandfather used to call it Slipton because of that slippery old street. If I’m really going to live here again, I might have to do something about that.’ He looked around him and sniffed the air. ‘Now, shall we take stock? What have we got here exactly? One brand-new chapel, for the ease of souls and your soul in particular. One chapel, not staffed by one priest, oh no. Not even staffed by two priests. Your chapel will be staffed by one chaplain, which is to be me, plus five priests and four clerks, am I right? At a cost, I am told, of forty pounds a year. Forty pounds a year for ever. Not to mention a stone-built college for us all to live out the fullness of our lives in prayer, study and, if I know anything about my fellow priests, in dice and wine and maybe even the odd woman.’

I frowned.

‘Oh yes,’ he went on. ‘It won’t all be holy and they may be very odd women.’

That wasn’t why I frowned. I knew William Batokewaye well enough to overlook the licence he had just allowed himself. I’d often heard he had a wife tucked out of sight though if so, that was one of the few things he had ever tried to keep from me. My reputation again, you see. That sort of thing was allowed for lower orders but not for a mendicant friar as he was, or at least had been. Would he presume to bring her here to Slapton? That might test our friendship. I frowned because since that moment in the chapel the echoes of sweet Elizabeth’s forgotten voice, waking all my love, had been gradually fading in my head and now, knowing I had lost the sound of her, I was bereft.

‘My question is this,’ he said. ‘Forgive me, I’m not complaining. I look forward to a comfortable retirement from the rigours of the last thirty years. It is generous of you in the extreme to provide it, but, quite apart from the fact that I would have been prepared to mumble masses for you all day and most of the night for half that sum all by myself, what’s it all for?’ The priest was a year older than me and had been asking me that sort of question for as long as I could remember. Having no arm for defence, he only ever knew how to attack.

‘It’s a Chantry. You know what it’s for.’ I opened my arms to indicate the courtyard in which we sat, the church we had just left and its new stone tower which soared into the air, dominating the little village, overpowering the spire of the village church below.

‘I know what a Chantry’s for. What I’m asking is why do you need one?’

I looked at him, suspecting a trap. He had always been a plain speaker and not one to follow slavishly along dogmatic lines, but this was going too far.

‘You can’t disapprove, William. You and I usually agree on what’s right and what’s wrong. I’ve built it so you and your priests will sing masses for my soul and for Elizabeth’s.’

‘And if we didn’t? If your soul had to stand up for itself without a lot of people, most of whom don’t know it very well, all singing flat on its behalf?’

I stared at him. I was deeply disturbed by his tone. This was dangerous ground. ‘You know the story? The story of de Mowbray?’ I sometimes felt it was all I had thought about for years now.

‘I might. Tell me anyway.’

‘He begged his chaplain to sing a mass for his soul the moment he died. Do you know what happened?’

Batokewaye sometimes looked as if he had been hewn from the huge trunk of an old elm tree and that look came upon him now, dense, unchangeable, so I went on. The chaplain ran straight from the deathbed. He was racing to the chapel but something stopped him. De Mowbray’s spectre, twisted and tortured. “You’ve broken your promise,” said the spectre. “No, I came straight here,” said the chaplain, “you died only a moment ago.” “In that time, twenty years have passed in Purgatory,” the ghost replied, “I have suffered twenty years of torment for your neglect. It is worse than Hell.”’

He just went on looking at me. I thought perhaps he hadn’t been listening.

‘Worse than Hell, William’ I said again. ‘If a few moments here is twenty years there, imagine how it will be. Your soul stays there, paying the price of your sins, until Judgement Day itself.’ It turned my guts around to think of it, to think I had that coming, hurtling at me.

He sighed. ‘Wherever I’ve been in the country, I’ve heard that story,’ he said. I’ve heard it said about Montague, Mauny, Beauchamp, Scrope, every single knight who has given up the ghost.’

‘Are you saying you don’t believe it?’

I’m saying that Purgatory is a very good idea from the clergy’s point of view. I’m delighted at the chance to live in luxury off a terrified Lord.’

‘Should we not be terrified of Purgatory? If we die in mortal sin aren’t we bound to suffer there? Isn’t that what the Bible says?’

The priest stared back at me, unblinking. ‘I know you, Guy. I’ve known you since long before you were a knight. I’ve heard everything you have to confess and I must say it’s been mild stuff. If you came to me to confess a real mortal sin, I’d know you were lying. All right, lying might be a sin but you’d have to try a lot harder to get committed to the eternal flames than by a grammatical paradox.’

He thought he knew me. He didn’t. I had told him nothing of the last and greatest of my three sins.