По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

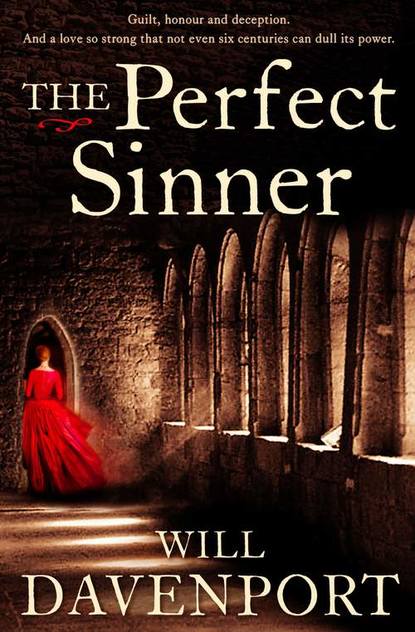

The Perfect Sinner

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Oh really. ‘Are you sure that’s what he said?’

‘I don’t lie, Sir Guy.’ For a short, fat studious man, he suddenly looked quite fierce.

‘I’m sure you don’t. Please excuse my bad manners. It’s just that I will not tolerate people abusing our king.’

He nodded. ‘And I won’t stand for people abusing my lord Lancaster.’

I didn’t show my amusement at the thought of him in hand-to-hand combat with Garciot because he so clearly meant what he said. The fight would have been over before a man could sneeze.

‘You have a high regard for Lancaster?’ I enquired.

That was who Garciot meant by his ‘upstart John’. King Edward’s youngest son, born only yards from where we now sat in Ghent and therefore known as John of Gaunt, as his mother, a Hainaulter, called the town. I wouldn’t have wanted to upset the squire further, but privately I had some sympathy for Garciot’s opinion. John had lately styled himself ‘King of Castile’, which seemed to me to be coming it a bit rich. He was never a man who had much understanding for those below him and I couldn’t fully forgive him for that slaughter at Limoges.

‘I had the highest regard for his Duchess.’ The squire sounded sad. He crossed himself, giving a deep sigh. ‘I wrote a poem to her.’

The beautiful Blanche. I thought of her and joined him in his silence because whenever I had seen Blanche I had thought immediately of Elizabeth, who had the same hair and the same forehead, but who shaded Blanche like a cathedral choir shades a tavern singer. I still long for Elizabeth every single day. We did not have enough time together. I know this life on earth is only our qualification for whichever place comes next, and I would not fear my time to come in Purgatory if it were just for myself. I deserve to suffer. No, what I cannot bear is the thought that I might spend an aeon there, locked away from her. Even worse is the other possibility that, through our sin, I might meet her there.

They sang her mass every day at Tewkesbury just as they would be singing it now at Slapton. I prayed that would work.

In the years we had together, right up until the end, she had a way of looking at me which suspended time and conscious thought so that we would gaze at each other in private delight. From across a room our souls could still embrace.

‘Sir Guy,’ said the squire, a little hesitantly, jerking me back to this noisy inn.

‘Yes?’

‘I would not wish to upset you or intrude upon you in any way,’ he said, waving a hand for another jug of wine, ‘but I have a great desire to hear men’s stories, and there is still so much I want to ask you in particular.’

‘Why me?’

‘Because I know that what the landlord said was right. Whenever I have heard your name spoken, it has always been with respect and trust. I want the chance to hear the story of great events told without having to worry about discerning truth and falsehood in the telling.’

‘Oh now be careful, young man. My memory is sixty-five years old. All memories are changed in the use and the retelling. I cannot guarantee you truth.’

‘I will take the risk.’

‘We have a long way to go,’ I said, ‘and precious little other company worth the name.’ It was clear we both felt the same way about our Genoese companions, and my archers, all fine fellows, were men of few words. ‘Ask what you want.’

‘When did you first meet this priest?’ he asked, staring over at William who was singing vigorously in the crowd of girls.

‘On the twenty-seventh day of August in the year thirteen hundred and forty six, just after the middle of the night.’

‘And you question the power of your memory?’ He raised an eyebrow. ‘That is a fuller answer than anyone could expect. Where was it?’

‘In the Valley of the Clerks.’

‘I don’t know of it. Where is it?’

‘It is some two hundred yards below the windmill on the down-slope of the plateau beside the village of Crécy-en-Ponthieu.’

‘Oh.’ He made a face. ‘That valley. Stupid of me. The great battle. Do you still remember it well?’

Remember it well? I thought of it almost as often as I thought of Elizabeth.

‘It’s an old tale and well-known,’ I said. ‘Were you born then?’

‘I was three.’

‘I met William in the night when the battle was over. The windmill was burning to light the battlefield and there were fires everywhere to honour the dead.’

‘More of theirs than ours.’

‘Oh yes. Far, far more. It had been a slaughter.’

‘Not just a slaughter,’ he objected. ‘An honourable and magnificent fight, surely? You had been outnumbered by ten to one.’

‘Time and willing lips will always twist a tale. Some say it was four to one, others say five. All the same, you could have searched high and low for honour on that field and not found quite enough of it.’

I hadn’t meant to say that out loud. He pounced on it. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Nothing,’ I said, ‘another time perhaps.’

‘Please go on. What happened that night?’

‘Nobody slept. You never do after a battle. You know that yourself, but the French didn’t seem to know it was over. More and more of them kept blundering up the valley like moths to a candle. They were wandering in from the far end, for hours afterwards, thinking to join in the spoils. They just didn’t seem to realise that all the bodies heaped up were their own countrymen.’ I drained my wine and he refilled it.

As ever, what was in my mind was the moment when the troops parted for the doomed charge of a blind king, John of Bohemia, lashed between his friends’ horses.

It was blind John’s fate that drew me to the heaps of dead. I thought I knew where I had seen him fall. A stupid thought. From up on the ridge by the windmill I had marked his passage fairly well, but then chaos hid his end and now, down below in the dark there were hills of dead piled to head-height, horses and men mixed together in heaps which had formed a rising barricade. The French had gone on leaping and clambering over that barricade, taking arrows for their trouble and piling it ever higher in the process.

I was weary to my bones, barely able to drag myself through the churned earth of the battlefield, stumbling over arrows and helmets and arms and legs, and I turned over a battalion of bodies before I found him. It was only when I saw the lashings around a harness that I finally knew where to look. Pulling the other corpses off the three of them left me sweating and soaked in crusting blood, and I couldn’t get them free, you see? There was a black horse lying across them, a real charger, solid, stiff and utterly dead. In the morning, they were using teams of men with ropes and poles to prise those piles apart, but there in the night, there was just me and the flickering light of the nearest fire. The legs I thought belonged to John were sticking out from under the horse, and I was pulling as hard as I could when I found I was no longer alone. A huge man in a woollen tunic had joined me.

‘You take one leg,’ he said, I’ll take the other.’

‘I’m not looting,’ I said sharply, because most of the men out on that field were our camp followers, using their knives to dispatch the nearly dead and cut from them whatever they could find of value. I had taken off my mail and I was in a plain jerkin. I could have been anyone and I didn’t need another fight.

‘I know that,’ he said. ‘I’ve seen you with the King all day, holding up the Standard. You did a good job. I don’t expect you need to loot, I guess you’ve got a castle or two of your own.’ There was nothing subservient about him, but right across that battlefield that night, in the aftermath of the desperate fight, men were talking to other men as equals and no one could be so proud as to mind.

‘One castle,’ I said, ‘and it leaks.’

He laughed harshly. ‘I know why you’re here. You and I saw the same thing,’ he said, ‘or thought we did, and we both need to know, don’t we?’

‘I’m Guy de Bryan,’ I said holding out a hand.

‘Are you indeed?’ he said as if he knew me. ‘Well now, there’s a fine thing. I am William Batokewaye,’ he squeezed my hand in his own much larger one. In those days he still had both arms. ‘In the service, for the present, of young Lord Montague, which is why I am here rooting around the carrion in the dark.’

Montague again. The Montagues were always embedded somewhere near the heart of my story. Let me get this right because, looking back, the order of all these events does get a little muddled in my head. That’s because so many of the things that really mattered in my life happened in such a short space of years, and so many of them involved the Montagues. They had given me no great reason for gratitude. Old Montague had harboured the villain Molyns, then imprisoned me, then done all he could to see his daughter, my dear Elizabeth, marry another man. When it came to the precipice of my sin, it was me who plunged over, but it was Montague’s hand that led me to the edge.

Now we had the new Earl of Salisbury, the younger Montague, and he was a fighter too, just like his wily, warrior father. Would he now set a curve of his own into the passage of my life? Molyns was still in his retinue. Molyns had done the deed that brought the two of us to root among these corpses in the dark.