Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, No.307

It is much matter for regret that the engineering explorations of Sir James Alexander and others on this proposed road should have ended in nothing being done. At an expense of L.60,000, the road, it is said, might have been made; and made it probably would have been, but for the freak of making a railway instead. This new project, started during the railway mania of 1845, and which would have cost that universal paymaster, Great Britain, not more than three or four millions of money(!), did not go on, which need not to be regretted; but it turned attention from the only practicable thing – a good common road; and till this day the road remains a desideratum.

After the pains we have taken to draw attention to the work of Sir James Alexander, it need scarcely be said that we recommend it for perusal. In conclusion, we may be allowed to express a hope that the author, the most competent man for the task perhaps in the Queen's dominions, will do something towards rousing public attention to the vast natural capabilities of New Brunswick – a colony almost at the door, and that might be readily made to receive the whole overplus population of the British islands. To effect such a grand social move as this would not be unworthy of the greatest minds of the age.

THE TAXES ON KNOWLEDGE

An association, as we learn, has sprung up in London with the view of procuring the abolition of all taxes on knowledge – meaning by that phrase the Excise duty on paper, the tax on foreign books, the duty on advertisements, and the penny stamp on newspapers; the whole of which yield a return to the Exchequer of L.1,266,733; but deducting certain expenses to which the government is put, the aggregate clear revenue is calculated to be about L.1,056,000.

We have been requested to give such aid as may be in our power to facilitate the objects of the Anti-tax-on-Knowledge Association, having, as is pretty correctly inferred, no small interest in seeing at least one department of the exaction – the duty on paper – swept away. So frequently, however, have we petitioned parliament on this subject, and with so little practical avail, that we have made up our minds to petition no more. If the public desire to get cheap newspapers, cheap literary journals, and cheap advertisements, they must say so, and take on themselves the trouble of agitating accordingly. This they have never yet done. They seem to have imagined that the question is one exclusively between publishers and papermakers and the government; whereas, in point of fact, it is as much a public question as that of the late taxes on food, and should be dealt with on the same broad considerations. We are, indeed, not quite sure that publishers, papermakers, and other tradesmen intimately concerned in the question are, as a body, favourable to the removal of the stamp, the Excise, and other taxes on their wares. Generally speaking, only a few of the more enterprising, and the least disposed to maintain a monopoly, have ever petitioned for the abolition of these taxes. This will seem curious, yet it can be accounted for. A papermaker, to pay the duty on the goods he manufactures, must have a large command of capital; comparatively few can muster this capital; hence few can enter the trade. London wholesale stationers, who, by advancing capital to the papermakers, acquire a species of thraldom over them, are, according to all accounts, by no means desirous to see the duties abolished; for if they were abolished, their money-lending and thirlage powers would be gone. So is it with the great monopolists of the newspaper press. As things stand, few can compete with them. But remove the existing imposts, and let anybody print a newspaper who likes, and hundreds of competitors in town and country would enter the field. There can be no doubt whatever that the stamp and advertisement-duty, particularly the latter, would long since have been removed but for the want of zeal shown by the London newspaper press. If these, however, be mistaken opinions, let us now see the metropolitan stationers and newspaper proprietors petition vigorously for the removal of the taxes that have been named.

But on the public the great burthen of the agitation must necessarily fall. Never would the legislature have abolished the taxes on bread from the mere complaints of the corn importers; nor will the taxes on knowledge be removed till the tax-payers show something like earnestness in pressing their demands. The modern practice of statesmanship is, to have no mind of its own: it has substituted agitation for intelligence, and only responds to clamour. The public surely can have no difficulty in making a noise! Let it do battle in this cause – cry out lustily – and we shall cheerfully help it. If it wont, why, then, we rather believe the matter must be let alone.

Who will dare to avow that the prize is not worthy of the contest? We do not apprehend that, by any process of cheapening, the newspaper press of Great Britain would ever sink to that pitch of foulness that seems to prevail in America. The tastes and habits of the people are against it; the law, strongly administered, is against it. The only change we would expect by the removal of the stamp-duty, and the substitution of, say, a penny postage, would be the rise of news-sheets in every town in the kingdom. And why not? Why, in these days of electric telegraph, should not every place have its own paper, unburthened with a stamp? Or why should the people of London, who do not post their newspapers, be obliged to pay for stamps which they never use? As to the advertisement-duty – an exaction of 1s. 6d. on every business announcement – its continuance is a scandal to common sense; and the removal of that alone would give an immense impetus to all branches of trade. The taxes which press on our own peculiar sheet we say nothing about, having already in many ways pointed out their effect in lessening the power of the printing-machine, and limiting the sphere of its public usefulness.

DR ARNOTT ON VENTILATION AS A PREVENTIVE OF DISEASE

Dr Neil Arnott has addressed a letter on this subject to the 'Times' newspaper. Any expression of opinion by him on such a subject, and more particularly with reference to the prevailing epidemics, must be deemed of so much importance, that we are anxious, as far as in our power, to keep it before the world. He commences by assuming, what will readily be granted, that fresh air for breathing is one of the essentials to life, and that the respiration of air poisoned by impure matter is highly detrimental to health, insomuch that it will sometimes produce the immediate destruction of life. The air acquires impurities from two sources in chief – solid and liquid filth, and the human breath. Persons exposed to these agencies in open places, as the manufacturers of manure in Paris, will suffer little. It is chiefly when the poison is caught and retained under cover, as in close rooms, that it becomes notedly active, its power, however, being always chiefly shown upon those whose tone of health has been reduced by intemperance, by improper food or drink, by great fatigue and anxiety, and, above all, by a habitual want of fresh air.

Dr Arnott regards ventilation not only as a ready means of rendering harmless the breath of the inmates of houses, as well as those living in hospitals and other crowded places, but as a good interim-substitute for a more perfect kind of draining than that which exists. 'To illustrate,' he says, 'the efficacy of ventilation, or dilution with fresh air, in rendering quite harmless any aërial poison, I may adduce the explanation given in a report of mine on fevers, furnished at the request of the Poor-Law Commissioners in 1840, of the fact, that the malaria or infection of marsh fevers, such as occur in the Pontine marshes near Rome, and of all the deadly tropical fevers, affects persons almost only in the night. Yet the malaria or poison from decomposing organic matters which causes these fevers is formed during the day, under the influence of the hot sun, still more abundantly than during the colder night; but in the day the direct beams of the sun warm the surface of the earth so intensely, that any air touching that surface is similarly heated, and rises away like a fire balloon, carrying up with it of course, and much diluting, all poisonous malaria formed there. During the night, on the contrary, the surface of the earth, no longer receiving the sun's rays, soon radiates away its heat, so that a thermometer lying on the ground is found to be several degrees colder than one hanging in the air a few feet above. The poison formed near the ground, therefore, at night, instead of being heated and lifted, and quickly dissipated, as during the day, is rendered cold, and comparatively dense, and lies on the earth a concentrated mass, which it may be death to inspire. Hence the value in such situations of sleeping apartments near the top of a house, or of apartments below, which shut out the night air, and are large enough to contain a sufficient supply of the purer day air for the persons using them at night, and of mechanical means of taking down pure air from above the house to be a supply during the night. At a certain height above the surface of the earth, the atmosphere being nearly of equal purity all the earth over, a man rising in a balloon, or obtaining air for his house from a certain elevation, might be considered to have changed his country, any peculiarity of the atmosphere below, owing to the great dilution effected before it reached the height, becoming absolutely insensible.

'Now, in regard to the dilution of aërial poisons in houses by ventilation, I have to explain that every chimney in a house is what is called a sucking or drawing air-pump, of a certain force, and can easily be rendered a valuable ventilating-pump. A chimney is a pump – first, by reason of the suction or approach to a vacuum made at the open top of any tube across which the wind blows directly; and, secondly, because the flue is usually occupied, even when there is no fire, by air somewhat warmer than the external air, and has therefore, even in a calm day, what is called a chimney-draught proportioned to the difference. In England, therefore, of old, when the chimney breast was always made higher than the heads of persons sitting or sleeping in rooms, a room with an open chimney was tolerably well ventilated in the lower part, where the inmates breathed. The modern fashion, however, of very low grates and low chimney openings, has changed the case completely; for such openings can draw air only from the bottom of the rooms, where generally the coolest, the last entered, and therefore the purest air, is found; while the hotter air of the breath, of lights, of warm food, and often of subterranean drains, &c., rises and stagnates near the ceilings, and gradually corrupts there. Such heated, impure air, no more tends downwards again to escape or dive under the chimneypiece, than oil in an inverted bottle, immersed in water, will dive down through the water to escape by the bottle's mouth; and such a bottle, or other vessel containing oil, and so placed in water with its open mouth downwards, even if left in a running stream, would retain the oil for any length of time. If, however, an opening be made into a chimney flue through the wall near the ceiling of the room, then will all the hot impure air of the room as certainly pass away by that opening as oil from the inverted bottle would instantly all escape upwards through a small opening made near the elevated bottom of the bottle. A top window-sash, lowered a little, instead of serving, as many people believe it does, like such an opening into the chimney flue, becomes generally, in obedience to the chimney draught, merely an inlet of cold air, which first falls as a cascade to the floor, and then glides towards the chimney, and gradually passes away by this, leaving the hotter impure air of the room nearly untouched.

'For years past I have recommended the adoption of such ventilating chimney openings as above described, and I devised a balanced metallic valve, to prevent, during the use of fires, the escape of smoke to the room. The advantages of these openings and valves were soon so manifest, that the referees appointed under the Building Act added a clause to their bill, allowing the introduction of the valves, and directing how they were to be placed, and they are now in very extensive use. A good illustration of the subject was afforded in St James's parish, where some quarters are densely inhabited by the families of Irish labourers. These localities formerly sent an enormous number of sick to the neighbouring dispensary. Mr Toynbee, the able medical chief of that dispensary, came to consult me respecting the ventilation of such places, and on my recommendation had openings made into the chimney flues of the rooms near the ceilings, by removing a single brick, and placing there a piece of wire gauze with a light curtain flap hanging against the inside, to prevent the issue of smoke in gusty weather. The decided effect produced at once on the feelings of the inmates was so remarkable, that there was an extensive demand for the new appliance, and, as a consequence of its adoption, Mr Toynbee had soon to report, in evidence given before the Health of Towns Commission, and in other published documents, both an extraordinary reduction of the number of sick applying for relief, and of the severity of diseases occurring. Wide experience elsewhere has since obtained similar results. Most of the hospitals and poor-houses in the kingdom now have these chimney-valves; and most of the medical men, and others who have published of late on sanitary matters, have strongly commended them. Had the present Board of Health possessed the power, and deemed the means expedient, the chimney openings might, as a prevention of cholera, almost in one day, and at the expense of about a shilling for a poor man's room, have been established over the whole kingdom.

'Mr Simpson, the registrar of deaths for St Giles's parish, an experienced practitioner, whose judgment I value much, related to me lately that he had been called to visit a house in one of the crowded courts, to register the death of an inmate from cholera. He found five other persons living in the room, which was most close and offensive. He advised the immediate removal of all to other lodgings. A second died before the removal took place, and soon after, in the poor-house and elsewhere, three others died who had breathed the foul air of that room. Mr Simpson expressed to me his belief that if there had been the opening described above into the chimney near the ceiling, this horrid history would not have been to tell. I believe so too, and I believe that there have been in London lately very many similar cases.

'The chimney-valves are part of a set of means devised by me for ventilation under all circumstances. My report on the ventilation of ships, sent at the request of the Board of Health, has been published in the Board's late Report on Quarantine, with testimony furnished to the Admiralty as to its utility in a convict ship with 500 prisoners. My observations on the ventilation of hospitals are also in the hands of the Board, but not yet published. All the new means have been freely offered to the public, but persons desiring to use them should be careful to employ competent makers.'

Having seen Dr Arnott's ventilators in operation in London and elsewhere, we can venture to recommend them as a simple and very inexpensive machinery for ventilating rooms with fires. The process is indeed generally known, and would be more extensively applied if people knew where to procure the ventilators. We have had many letters of inquiry on this subject, and could only refer parties to 'any respectable ironmongers.' But unfortunately, as it appears, there are hundreds of respectable ironmongers who never heard of the article in question, and our recommendation goes pretty much for nothing. Curious how a little practical difficulty will mar a great project! We trust that the worthy doctor will try to let it be known where his ventilators are to be had in town and country.

AN OLD-FASHIONED DITTY

I've tried in much bewilderment to findUnder which phase of loveliness in theeI love thee best; but oh, my wandering mindHovers o'er many sweets, as doth a bee,And all I feel is contradictory.I love to see thee gay, because thy smileIs sweeter than the sweetest thing I know;And then thy limpid eyes are all the whileSparkling and dancing, and thy fair cheeks glowWith such a sunset lustre, that e'en soI love to see thee gay.I love to see thee sad, for then thy faceExpresseth an angelic misery;Thy tears are shed with such a gentle grace,Thy words fall soft, yet sweet as words can be,That though 'tis selfish, I confess, in me,I love to see thee sad.I love to hear thee speak, because thy voiceThan music's self is yet more musical,Its tones make every living thing rejoice;And I, when on mine ear those accents fall,In sooth I do believe that most of allI love to hear thee speak.Yet no! I love thee mute; for oh, thine eyesExpress so much, thou hast no need of speech!And there's a language that in silence lies,When two full hearts look fondness each to each,Love's language that I fain to thee would teach,And so I love thee mute.Thus I have come to the conclusion sweet,Nothing thou dost can less than perfect be;All beauties and all virtues in thee meet;Yet one thing more I'd fain behold in thee —A little love, a little love for me.Marian.DEER

The deer is the most acute animal we possess, and adopts the most sagacious plans for the preservation of its life. When it lies, satisfied that the wind will convey to it an intimation of the approach of its pursuer, it gazes in another direction. If there are any wild birds, such as curlews or ravens, in its vicinity, it keeps its eye intently fixed on them, convinced that they will give it a timely alarm. It selects its cover with the greatest caution, and invariably chooses an eminence from which it can have a view around. It recognises individuals, and permits the shepherds to approach it. The stags at Tornapress will suffer the boy to go within twenty yards of them, but if I attempt to encroach upon them they are off at once. A poor man who carries peats in a creel on his back here, may go 'cheek-for-jowl' with them: I put on his pannier the other day, and attempted to advance, and immediately they sprung away like antelopes. An eminent deer-stalker told me the other day of a plan one of his keeper's adopted to kill a very wary stag. This animal had been known for years, and occupied part of a plain from which it could perceive the smallest object at the distance of a mile. The keeper cut a thick bush, which he carried before him as he crept, and commenced stalking at eight in the morning; but so gradually did he move forward, that it was five P.M. before he stood in triumph with his foot on the breast of the antlered king. 'I never felt so much for an inferior creature,' said the gentleman, 'as I did for this deer. When I came up it was panting life away, with its large blue eyes firmly fixed on its slayer. You would have thought, sir, that it was accusing itself of simplicity in having been so easily betrayed.' —Inverness Courier.

IVORY

At the quarterly meeting of the Geological and Polytechnic Society of the West Riding of Yorkshire, held in the Guildhall in Doncaster, on Wednesday last, Earl Fitzwilliam in the chair, Mr Dalton of Sheffield read a paper on 'ivory as an article of manufacture.' The value of the annual consumption in Sheffield was about L.30,000, and about 500 persons were employed in working it up for trade. The number of tusks to make up the weight consumed in Sheffield, about 180 tons, was 45,000. According to this, the number of elephants killed every year was 22,500; but supposing that some tusks were cast, and some animals died, it might be fairly estimated that 18,000 were killed for the purpose. —Yorkshire Gazette.

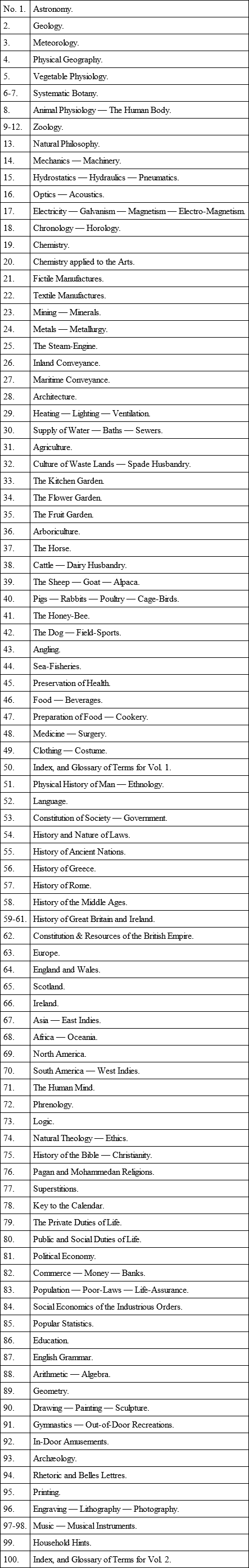

CHAMBERS'S INFORMATION FOR THE PEOPLEThe new and improved edition of this work, which has been in course of publication during the last two years, is now completed. In its entire form it consists of two volumes royal 8vo., price 16s. in cloth boards.

The following is the list of subjects of which the work is composed; each subject being generally confined to a single number. Price of each number 1½d. The work is largely illustrated with wood-engravings: —

1

The sad story of Queen Matilda, who was sister to our George III., is related in full detail in an interesting book recently published, 'Memoirs of Sir Robert Murray Keith,' 2 vols.

2

Thiele's Collection of Popular Danish Traditions.

3

See Popular Rhymes of Scotland, third edition, p. 229.

4

London: Colburn. 2 vols. with Plates. 1849.