The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 323, July 19, 1828

We lay eight weeks in the river Gaboon, where he had plenty of excellent food, but was never suffered to leave his cage, on account of the deck being always filled with black strangers, to whom he had a very decided aversion, although he was perfectly reconciled to white people. His indignation, however, was constantly excited by the pigs, when they were suffered to run past his cage; and the sight of one of the monkeys put him in a complete fury. While at anchor in the before-mentioned river, an orang-outang (Símia Sátyrus) was brought for sale, and lived three days on board; and I shall never forget the uncontrollable rage of the one, or the agony of the other, at this meeting. The orang was about three feet high, and very powerful in proportion to his size; so that when he fled with extraordinary rapidity from the panther to the further end of the deck, neither men nor things remained upright when they opposed his progress: there he took refuge in a sail, and although generally obedient to the voice of his master, force was necessary to make him quit the shelter of its folds. As to the panther, his back rose in an arch, his tail was elevated and perfectly stiff, his eyes flashed, and, as he howled, he showed his huge teeth; then, as if forgetting the bars before him, he tried to spring on the orang, to tear him to atoms. It was long before he recovered his tranquillity; day and night he appeared to be on the listen; and the approach of a large monkey we had on board, or the intrusion of a black man, brought a return of his agitation.

We at length sailed for England, with an ample supply of provisions; but, unhappily, we were boarded by pirates during the voyage, and nearly reduced to starvation. My panther must have perished had it not been for a collection of more than three hundred parrots, with which we sailed from the river, and which died very fast while we were in the northwest trades. Saï’s allowance was one per diem, but this was so scanty a pittance that he became ravenous, and had not patience to pick all the feathers off before he commenced his meal. The consequence was, that he became very ill, and refused even this small quantity of food. Those around tried to persuade me that he suffered from the colder climate; but his dry nose and paw convinced me that he was feverish, and I had him taken out of his cage; when, instead of jumping about and enjoying his liberty, he lay down, and rested his head upon my feet. I then made him three pills, each containing two grains of calomel. The boy who had the charge of him, and who was much attached to him, held his jaws open, and I pushed the medicine down his throat. Early the next morning I went to visit my patient, and found his guard sleeping in the cage with him; and having administered a further dose to the invalid, I had the satisfaction of seeing him perfectly cured by the evening. On the arrival of the vessel in the London Docks, Saï was taken ashore, and presented to the Duchess of York, who placed him in Exeter Change, to be taken care of, till she herself went to Oatlands. He remained there for some weeks, and was suffered to roam about the greater part of the day without any restraint. On the morning previous to the Duchess’s departure from town, she went to visit her new pet, played with him, and admired his healthy appearance and gentle deportment. In the evening, when her Royal Highness’ coachman went to take him away, he was dead, in consequence of an inflammation on his lungs—Loudon’s Magazine of Natural History.

Manners & Customs of all Nations

SACRAMENTAL BREAD

The church of Rome, in the height of its power, was extremely scrupulous in all that related to the sacramental bread. According to Steevens, in his Monasticon, they first chose the wheat, grain by grain, and washed it very carefully. Being put into a bag, appointed only for that use, a servant, known to be a just man, carried it to the mill, worked the grindstones, covering them with curtains above and below; and having put on himself an albe, covered his face with a veil, nothing but his eyes appearing. The same precaution was used with the meal. It was not baked till it had been well washed; and the warden of the church, if he were either priest or deacon, finished the work, being assisted by two other religious men, who were in the same orders, and by a lay brother, particularly appointed for that business. These four monks, when matins were ended, washed their faces and hands. The three first of them put on albes; one of them washed the meal with pure, clean water, and the other two baked the hosts in the iron moulds. So great was the veneration and respect, say their historians, the monks of Cluni paid to the Eucharist! Even at this day, in the country, the baker who prepares the sacramental wafer, must be appointed and authorized to do it by the Catholic bishop of the district, as appears by the advertisement inserted in that curious book, published annually, The Catholic Laity’s Directory.

FOSTER CHILDREN

There still remains in the Hebrides, though it is passing fast away, the custom of fosterage. A laird, a man of wealth and eminence, sends his child, either male or female, to a tacksman or tenant to be fostered. It is not always his own tenant, but some distant friend that obtains this honour; for an honour such a trust is very reasonably thought. The terms of fosterage seem to vary in different islands. In Mull, the father sends with his child a certain number of cows, to which the same number is added by the fosterer. The father appropriates a proportionable extent of ground, without rent, for their pasturage. If every cow bring a calf, half belongs to the fosterer, and half to the child; but if there be only one calf between two cows, it is the child’s; and when the child returns to the parents, it is accompanied with all the cows given, both by the father and by the fosterer, with half of the increase of the stock by propagation. These beasts are considered as a portion, and called Macalive cattle, &c.

Children continue with the fosterer perhaps six years; and cannot, where this is the practice, be considered as burdensome. The fosterer, if he gives four cows, receives likewise four, and has, while the child continues with him, grass for eight without rent, with half the calves, and all the milk, for which he pays only four cows, when he dismisses his dalt, for that is the name for a fostered child.—Johnson’s Journey.

THE IRISH PEOPLE

Holinshed, speaking of the Irish, observes:—“Greedy of praise they be, and fearful of dishonour; and to this end they esteem their poets, who write Irish learnedly, and pen their sonnets heroical, for the which they are bountifully rewarded; if not, they send out libels in dispraise, whereof the lords and gentlemen stand in great awe. They love tenderly their foster children, and bequeath to them a child’s fortune, whereby they nourish sure friendship,—so beneficent every way, that commonly 500 cows and better are given in reward to win a nobleman’s child to foster; they love and trust their foster children more than their own. Proud they are of long crisped bushes of hair, which they term libs. They observe divers degrees, according to which each man is regarded. The basest sort among them are little young wasps, called daltins: these are lacqueys, and are serviceable to the grooms, or horseboys, who are a degree above the daltins. The third degree is the kaerne, which is an ordinary soldier, using for weapon his sword and target, and sometimes his piece, being commonly so good marksmen, as they will come within a score of a great cartele. The fourth degree is a gallowglass, using a kind of poll-axe for his weapon, strong, robust men, chiefly feeding on beef, pork, and butter. The fifth degree is to be a horseman, which is the chiefest, next to the lord and captain. These horsemen, when they have no stay of their own, gad and range from house to house, and never dismount till they ride into the hall, and as far as the tables.”

MARRIAGE

The minister of Logierait, in Perthshire, in his statistical account of that parish, supplies us with the following curious information on this and other marriage ceremonies:—“Immediately before the celebration of the marriage ceremony, every knot about the bride and bridegroom (garters, shoe-strings, strings of petticoats, &c.) is carefully loosed. After leaving the church, the whole company walk round it, keeping the church walls always upon the right hand; the bridegroom, however, first retires one way, with some young men, to tie the knots that were loosened about him, while the young married woman, in the same manner, retires somewhere else to adjust the disorder of her dress.”

NEEDFIRE

The following extract contains a distinct and interesting account of this very ancient superstition, as used in Caithness:

“In 1788, when the stock of any considerable farmer was seized with the murrain, he would send for one of the charm doctors to superintend the raising of a needfire. It was done by friction, thus: upon any small island, where the stream of a river or burn ran on each side, a circular booth was erected, of stone and turf, as it could be had, in which a semicircular or highland couple of birch, or other hard wood, was set; and, in short, a roof closed on it. A straight pole was set up in the centre of this building, the upper end fixed by a wooden pin to the top of the couple, and the lower end in an oblong trink in the earth or floor; and lastly, another pole was set across horizontally, having both ends tapered, one end of which was supported in a hole in the side of the perpendicular pole, and the other end in a similar hole in the couple leg. The horizontal stick was called the auger, having four short arms or levers fixed in its centre, to work it by; the building having been thus finished, as many men as could be collected in the vicinity, (being divested of all kinds of metal in their clothes, &c.) would set to work with the said auger, two after two, constantly turning it round by the arms or levers, and others occasionally driving wedges of wood or stone behind the lower end of the upright pole, so as to press it the more on the end of the auger; by this constant friction and pressure, the ends of the auger would take fire, from which a fire would be instantly kindled, and thus the needfire would be accomplished. The fire in the farmer’s house, &c. was immediately quenched with water, a fire kindled from this needfire, both in the farm-house and offices, and the cattle brought to feel the smoke of this new and sacred fire, which preserved them from the murrain. So much for superstition.—It is handed down by tradition, that the ancient Druids superintended a similar ceremony of raising a sacred fire, annually, on the first day of May. That day is still, both in the Gaelic and Irish dialects, called Lâ-bealtin, i.e. the day of Baal’s fire, or the fire dedicated to Baal, or the sun.”

UNSPOKEN WATER

In Scotland, water from under a bridge, over which the living pass and the dead are carried, brought in the dawn or twilight to the house of a sick person, without the bearer’s speaking, either in going or returning, is called Unspoken Water.

The modes of application are various. Sometimes the invalid takes three draughts of it before anything is spoken. Sometimes it is thrown over the houses the vessel in which it was contained being thrown after it. The superstitious believe this to be one of the most powerful charms that can be employed for restoring a sick person to health.

The purifying virtue attributed to water, by almost all nations, is so well known as to require no illustration. Some special virtue has still been ascribed to silence in the use of charms, exorcisms, &c. I recollect, says Mr. Jamieson, being assured at Angus, that a Popish priest in that part of the country, who was supposed to possess great power in curing those who were deranged, and in exorcising demoniacs, would, if called to see a patient, on no account utter a single word on his way, or after arriving at the house, till he had by himself gone through all his appropriate forms in order to effect a cure. Whether this practice might be founded on our Lord’s injunction to the Seventy, expressive of the diligence he required, Luke x. 4, “Salute no man by the way,” or borrowed from heathen superstition, it is impossible to ascertain. We certainly know that the Romans viewed silence as of the utmost importance in their sacred rites. Hence the phrase of Virgil,—

“Fida silentia sacris.”Fauere sacris, fauere linguis, and pascere linguam, were forms of speech appropriated to their sacred rites, by which they enjoined silence, that the act of worship might not be disturbed by the slightest noise or murmur. Hence also they honoured Harpocrates as the god of silence; and Numa instituted the worship of a goddess under the name of Tacita.

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

FILTERING APPARATUS

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

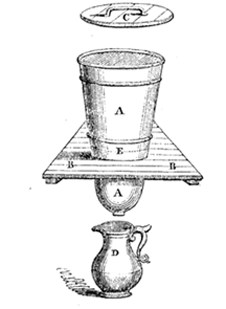

A A. The Pot. B B. The Triangular Board. C. The Cover. D. Vessel to receive the Filtered Water. E. Dotted Line, showing the Proportion of Charcoal and Sand.

Herewith I send you an outline drawing of an economical filtering apparatus, suitable for the use of any dwelling. Its construction is perfectly simple, and at the cost of a few shillings in its erection. The pot consists of an unglazed inverted vessel, manufactured at potteries for the use of sugar-bakers, and placed through a hole in a triangular board, resting upon two ledges, occupying a corner in a kitchen or any other apartment. In the inside of the pot a bushel of the whitest sand is to be introduced; which sand, after being washed in a clean tub with about three changes of water, to dissolve and clear away the clayey matter, is to be mixed with half a peck of finely-bruised charcoal. This will fill about one-third of the pot; but before the sand is placed in the vessel, the small hole at the bottom of the pot should have an oyster-shell placed over it, with the convex side uppermost, to prevent the sand washing through. This filters foul water perfectly pellucid and clear very quickly, as I have seen its effects for years with the most perfect success. When the sand becomes foul by time, it can be taken out and washed, or fresh materials can be repeated; great care should be observed not to put more water in the pot than your vessel underneath will receive.

JNO. FIELD.Effects of Lightning

The analogy between the electric spark, and more especially of the explosive discharge of the Leyden jar, with atmospheric lightning and thunder, is too obvious to have escaped notice, even in the early periods of electrical research. It had been observed by Dr. Wall and by Gray, and still more pointedly remarked by the Abbé Nollet. Dr. Franklin was so impressed with the many points of resemblance between lightning and electricity, that he was convinced of their identity, and determined to ascertain by direct experiment the truth of his bold conjecture. A spire which was erecting at Philadelphia he conceived might assist him in this inquiry; but, while waiting for its completion, the sight of a boy’s kite, which had been raised for amusement, immediately suggested to him a more ready method of attaining his object. Having constructed a kite by stretching a large silk handkerchief over two sticks in the form of a cross, on the first appearance of an approaching storm, in June 1752, he went out into a field, accompanied by his son, to whom alone he had imparted his design. Having raised his kite, and attached a key to the lower end of the hempen string, he insulated it by fastening it to a post, by means of silk, and waited with intense anxiety for the result. A considerable time elapsed without the apparatus giving any sign of electricity, even although a dense cloud, apparently charged with lightning, had passed over the spot on which they stood. Franklin was just beginning to despair of success, when his attention was caught by the bristling up of some loose fibres on the hempen cord; he immediately presented his knuckle to the key, and received an electric spark. Overcome with the emotion inspired by this decisive evidence of the great discovery he had achieved, he heaved a deep sigh, and conscious of an immortal name, felt that he could have been content if that moment had been his last. The rain now fell in torrents, and wetting the string, rendered it conducting in its whole length; so that electric sparks were now collected from it in great abundance.

It should be noticed, however, that about a month before Franklin had made these successful trials, some philosophers, in particular Dalibard and De Lors, had obtained similar results in France, by following the plan recommended by Franklin. But the glory of the discovery is universally given to Franklin, as it was from his suggestions that the methods of attaining it were originally derived.

This important discovery was prosecuted with great ardour by philosophers in every part of Europe. The first experimenters incurred considerable risk in their attempts to draw down electricity from the clouds, as was soon proved by the fatal catastrophe, which, on the 6th of August, 1753, befel Professor Richman, of Petersburg. He had constructed an apparatus for observations on atmospherical electricity, and was attending a meeting of the Academy of Sciences, when the sound of distant thunder caught his ear. He immediately hastened home, taking with him his engraver, Sokolow, in order that he might delineate the appearances that should present themselves. While intent upon examining the electrometer, a large globe of fire flashed from the conducting rod, which was insulated, to the head of Richman, and passing through his body, instantly deprived him of life. A red spot was found on his forehead, where the electricity had entered, his shoe was burst open, and part of his clothes singed. His companion was struck down, and remained senseless for some time; the door-case of the room was split, and the door itself torn off its hinges.

The protection of buildings from the effects of lightning, is the most important practical application of the theory of electricity. Conductors for this should be formed of metallic rods, pointed at the upper extremity, and placed so as to project a few feet above the highest part of the building they are intended to secure; they should be continued without interruption till they descend into the ground, below the foundation of the house. Copper is preferable to iron as the material for their construction, being less liable to destruction by rust, or by fusion, and possessing also a greater conducting power. The size of the rods should be from half an inch to an inch in diameter, and the point should be gilt, or made of platina, that it may be more effectually preserved from corrosion. An important condition in the protecting conductor is, that no interruption should exist in its continuity from top to bottom; and advantage will result from connecting together by strips of metal all the leaden water pipes, or other considerable masses of metal in or about the building, so as to form one continuous system of conductors, for carrying the electricity by different channels to the ground. The lower end of the conductors should be carried down into the earth till it reaches either water, or at least a moist stratum.—Library of Useful Knowledge.

The Sketch-Book

THE MYSTERIOUS TAILOR

A Romance of High HolbornIt came to pass that, towards the close of 1826, I found occasion to change my tailor, and by chance, or the recommendation of friends—I cannot now remember which—applied to one who vegetated in that particular region of the metropolis where the rivers of Museum-street and Drury-lane (to adopt the language of metaphor) flow into and form the capacious estuary of High Holborn. Whoever has sailed along, or cast anchor in this confluence, must have seen the individual I allude to. He sits—I should perhaps say sat, inasmuch as he is since defunct—bolt upright, with a pen behind his ear, in the centre of a dingy, spectral-looking shop, quaintly hung round with clothes, of divers forms and patterns, in every stage of existence—from the first crude conception of the incipient surtout or pantaloons, down to the last glorious touch that immortalizes the artist. His figure is slim and undersized; his cheeks are sallow, with two furrows on each side his nose, filled not unfrequently with snuff; his eyes project like lobsters’, and cast their shifting glances about with a vague sort of mysterious intelligence; and his voice—his startling, solemn, unearthly voice—seems hoarse with sepulchral vapours, and puts forth its tones like the sighing of the wind among tombs. With regard to his dress, it is in admirable keeping with his countenance. He wears a black coat, fashioned in the mould of other times, with large cloth buttons and flowing skirts; drab inexpressibles, fastened at the knee with brass buckles; gaiters, which, reaching no higher than the calf of the leg, set up independent claims to eccentricity and exact consideration on their own account; creaking, square-toed shoes; and a hat, broad in front, pinched up at the sides, verging to an angle behind, and worn close over the forehead, with the lower part resting on the nose. His manner is equally peculiar; it cannot be called vulgar, nor yet genteel—for it is too passive for the one, and too pompous for the other; it forms, say, a sort of compromise between the two, with a slight infusion of pedantry that greatly adds to its effect.

On reaching this oddity’s abode, I at once proceeded to business; and was promised, in reply, the execution of my order on the customary terms of credit. Thus far is strictly natural. The clothes came home, and so, with admirable punctuality, did the bill; but the death of a valued friend having withdrawn me, soon afterwards, from London, six months elapsed; at the expiration of which time I was refreshed, as agreed on, by a pecuniary application from my tailor. Perhaps I should here mention, to the better understanding of my tale, that I am a medical practitioner, of somewhat nervous temperament, derived partly from inheritance, and partly from an inveterate indulgence of the imagination. My income, too—which seldom or never encumbers a surgeon who has not yet done walking the hospitals—is limited, and, at this present period, was so far contracted as to keep me in continual suspense. In this predicament my tailor’s memorandum was any thing but satisfactory. I wrote accordingly to entreat his forbearance for six months longer, and, as I received no reply, concluded that all was satisfactorily arranged. Unluckily, however, as I was strolling, about a month afterwards, along the Strand, I chanced to stumble up against him. The shock seemed equally unexpected on both sides; but my tailor (as being a dun) was the first to recover self-possession; and, with a long preliminary hem!—a mute, but expressive compound of remonstrance, apology, and resolution—opened his fire as follows:—

“I believe, sir, your name is D–?”

“I believe it is, sir.”

“Well, then, Mr. D–, touching that little account between us, I have to request, sir, that—”

“Very good; nothing can be more reasonable; wait the appointed time, and you shall have all.”

This answer served, in some degree, to appease him; no, not exactly to appease him, because that would imply previous excitement, and he was invariably imperturbable in manner; it satisfied him, however, for the present, and he forthwith walked away, casting on me that equivocal sort of look with which Ajax turned from Ulysses, or Dido from Æneas, in the Shades.

A lapse of a few weeks ensued, during which I heard nothing further from my persecutor; when, one dark November evening—one of those peculiarly English evenings, full of fog and gloom, when the half-frozen sleet, joined in its descent by gutters from the house-tops, comes driving full in your face, blinding you to all external objects—on one of these blessed evenings, on my road to Camden Town, I chanced to miss my way, and was compelled, notwithstanding a certain shyness towards strangers, to ask my direction of the first respectable person I should meet. Many passed me by, but none sufficiently prepossessing; when, on turning down some nameless street that leads to Tottenham Court-road, I chanced to come behind a staid-looking gentleman, accoutred in a dark brown coat, with an umbrella—the cotton of which had shrunk half-way up the whalebone—held obliquely over his head. Hastily stepping up to him, “Pray, sir,” said I, “could you be kind enough to direct me to – place, Camden Town?”