The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 360, March 14, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 360, March 14, 1829

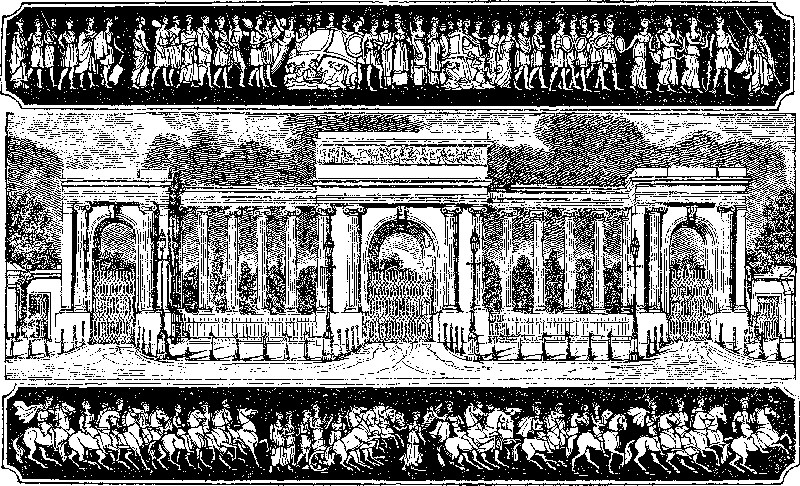

Grand Entrance to Hyde Park

Frieze.

GRAND ENTRANCE TO HYDE PARK

The great Lord Burleigh says, "A realm gaineth more by one year's peace than by ten years' war;" and the architectural triumphs which are rising in every quarter of the metropolis are strong confirmation of this maxim.

One of these triumphs is represented in the annexed engraving, viz. the grand entrance to Hyde Park, erected from the designs of Decimus Burton, Esq. It consists of a screen of handsome fluted Ionic columns, with three carriage entrance archways, two foot entrances, a lodge, &c. The extent of the whole frontage is about 107 feet. The central entrance has a bold projection: the entablature is supported by four columns; and the volutes of the capitals of the outside column on each side of the gateway are formed in an angular direction, so as to exhibit two complete faces to view. The two side gateways, in their elevations, present two insulated Ionic columns, flanked by antae. All these entrances are finished by a blocking, the sides of the central one being decorated with a beautiful frieze, representing a naval and military triumphal procession, which our artist has copied and represented in distinct engravings. This frieze was designed by Mr. Henning, jun., son of Mr. Henning, so well known for his admirable models of the Elgin marbles. It possesses great classical merit, and the model was exhibited last season in the sculpture-room of the Suffolk-street Gallery.

The gates were manufactured by Messrs. Bramah. They are of iron, bronzed, and fixed or hung to the piers by rings of gun-metal. The design consists of a beautiful arrangement of the Greek honeysuckle ornament; the parts being well defined, and the raffles of the leaves brought out in a most extraordinary manner. The hanging of the gates is also very ingenious.

Mr. Soane's proposed entrances to Piccadilly and St. James's and Hyde Parks, are generally considered superior to those that have been adopted. The park entrances were to consist of two triumphal arches connected with each other by a colonnade and arches stretching across Piccadilly. The same ingenious architect likewise designed a new palace at the top of Constitution Hill, from which to the House of Lords the King should pass Buckingham House, Carlton House, a splendid Waterloo and Trafalgar monument, a fine triumphal arch, the Privy Council Office, Board of Trade, and the new law courts.

LINES

On the origin of the application of the name of the "Fleur de Souvenance," (modern "Forget-me-not,") to the Myosotis Scorpiodis.

(For the Mirror.)A gallant knight and a lady brightWalk'd by a crystal lake;The twin'd oaks made a grateful shadeAbove the fangled brake,While the trembling leaves of aspen treesA murmuring music make.And as they spoke, round them echoes wokeTo tales of love and glory;The knight was brave, though of love the slave,And the dame lov'd gallant story—Proudly he told deeds gentle and bold,Of warriors dead or hoary.Like babe at rest on its mother's breast,On that an island lay—So still and fair reigned Nature there—So bright the glist'ring spray,You might have thought the scene had been wroughtBy spell of faun or fay.On the island's edge, midst tangled sedge,Lay a wreath of wild flow'rs blue—The broad flag-leaf was their sweet relief,When the heat too fervid grew;And the willow's shade a shelter made,When stormy tempests blew.And as they stood, the faithful floodGave back ev'ry line and traceOf earth below and heaven above,And their own forms gallant grace—For forms more fair than that lovely pairNe'er shone on its liquid face."I would a flower from that bright bowerSome nymph would waft to me—For in my eyes a dearer prizeThan glitt'ring gem 'twould be—For its changeless blue seems emblem trueOf love's own constancy."The maiden spake, and no more the lakeIn slumb'ring stillness lay,For from the side of his destin'd brideThe knight has pass'd away;In vain the maid's soft words essay'dHis rash pursuit to stay.He has reach'd the tower, and pluck'd the flower.And turn'd from the verdant spot.Ah, hapless knight! some Naiad brightWoo'd thee to her coral grot;And forbids that more to touch that shoreShall ever be thy lot.Vainly he tried to gain the side,Where knelt his lady-love;Flagg'd every limb, his eyes grew dim,But still the spirit strove.One effort more—he flings to shoreThe flow'r so dear to prove.'Tis past! 'tis past! that look his last,That fond sad glance of loveThe bubbling wave his farewell gaveIn the moan, "Forget me not."D.A.HThe above incident occurred in the time of Edward IV.

HAVER BREAD

In the MIRROR, No. 358, the article headed "Memorable Days," the writer, in that part of which the Avver Bread is treated of, says it is made of oats leavened and kneaded into a large, thin, round cake, which is placed upon a girdle over the fire; adding, that he is totally at a loss for a definition of the word Avver; that he has sometimes thought avver, means oaten; which I think, correct, it being very likely a corruption of the French, avoine, oats; introduced among many others, into the Scottish language, during the great intimacy which formerly existed between France and Scotland; in which latter country a great many words were introduced from the former, which are still in use; such as gabart, a large boat, or lighter, from the French gabarre; bawbee, baspiece, a small copper coin; vennell, a lane, or narrow street, which still retains its original pronunciation and meaning. Enfiler la vennel; a common figurative expression for running away is still in use in France. Apropos of vennell, Dr. Stoddard, in a "Pedestrian Tour through the Land of Cakes," when a young man, says he could not trace its meaning in any language, (I speak from memory) also made the same observation where I was; being at that time on intimate terms with the doctor, I pointed out to him its derivation from the Latin into the French, and thence, probably, into the Scotch; the embryo L.L.D. stared, and seemed chagrined, at receiving such information from a

CREOLE.P.S. In no part of Great Britain, I believe, is oaten bread so much used as in Scotland; from whence the term, "The Land of Cakes is derived." In some parts of France, Pain d'avoine has been in use in my time.

EPITOME OF THE CRUSADES

(For the Mirror.)The first Crusade1 to the Holy Land was undertaken by numerous Christian princes, who gained Jerusalem after it had been in possession of the Saracens four hundred and nine years. Godfrey, of Boulogne, was then chosen king by his companions in arms; but he had not long enjoyed his new dignity, before he had occasion to march out against a great army of Turks and Saracens, whom he overthrew, and killed one hundred thousand of their men, besides taking much spoil. Shortly after this victory, a pestilence happened, of which multitudes died; and the contagion reaching Godfrey, the first Christian King of Jerusalem, he also expired, on the 18th of July, 1100, having scarcely reigned a full year.

Godfrey's successors, the Baldwins, defeated the Turks in many engagements. In the reign of Baldwin III., however, the Christians lost Edessa, a circumstance which affected Pope Eugenius III. to such a degree, that he prevailed on Conrad III., Emperor of Germany, to relieve his brethren in Syria. In the year 1146, therefore, Conrad marched through Greece, and soon afterwards encountered the Turkish army, which he routed; he then proceeded to Iconium, the principal seat of the Turks in Lesser Asia; but, for want of provisions and health, was compelled to relinquish his design of taking that city, and to return home. Much about the same period, Lewis VIII., of France, made an expedition to the Holy Land, but was wholly unsuccessful in his attempts against the enemy. Notwithstanding these failures, King Baldwin, relying on his own strength, gained possession of Askalon, and defeated the Turks in numerous actions. Previous to his death, which was caused by poison, in 1163, he was the victorious sovereign of Jerusalem and the greatest part of Syria.

During the reign of Baldwin IV., Saladin, Sultan of Egypt, invaded Palestine, and took several towns, notwithstanding the valour of the Christians. In the succeeding reign of King Guy, however, the Christians, still unfortunate, received a decisive blow, which tended to the decline of their independence in the Holy Land; for, among other places of importance, Saladin made a capture of Jerusalem, and took its king prisoner. When the conqueror entered the holy city, he profaned every sacred place, save the Temple of the Sepulchre, (which the Christians redeemed with an immense sum of money,) and drove the Latin Christians from their abodes, who were only allowed to carry what they could hastily collect on their backs, either to Tripoly, Antioch, or Tyre, the only three places which then remained in the Christians' possession. All the monuments were demolished, except those of our Saviour, King Godfrey, and Baldwin I.2 The city was yielded to the captors on the 2nd of October, 1187, after the Christians had possessed it about eighty-nine years.

These calamitous transactions in Palestine greatly alarmed all Europe, and several princes speedily resolved to oppose the career of the oppressors, and to leave no means untried of regaining the kingdom of Jerusalem. In furtherance of this design, the Emperor Frederic marched into Palestine with a powerful army, and defeated the Turks near Melitena; he afterwards met them near Comogena, where he also routed them, but was unhappily killed in the action. Some time after this, King Philip, of France, and Richard I., of England, engaged in a crusade for the relief of the Christians. Philip arrived first, and proceeded to Ptolemais, which King Guy, having obtained his liberty, was then besieging. King Richard, in his passage, was driven with his fleet upon the coast of Cyprus, but was not permitted to land; this so highly offended him, that he landed his whole army by force, and soon over-ran the island. He was at length opposed by the king of Cyprus, whom he took prisoner, and carried in chains to Ptolemais, where he was welcomed with great rejoicings by the besiegers, who stood in much need of assistance. It would he superfluous to relate here the particulars of the siege; let it suffice to say, that after a general assault had been given, a breach was made, so that the assailants were enabled to enter the city, which Saladin surrendered to them upon articles, on the 12th of July, 1191. King Richard here obtained the title of Coeur de Lion, for having taken down Duke Leopold's standard, that was first fixed in the breach, and placed his own in its stead.

After the taking of Ptolemais, King Philip and many other princes returned home, leaving King Richard in Palestine to prosecute the war in concert with Guy, whom Richard, in a short time afterwards, persuaded to accept of the crown of Cyprus, in lieu of his pretences to Jerusalem. By these crafty means, Richard caused himself to be proclaimed King of Jerusalem; but while he was preparing to besiege that city, he received news that the French were about to invade England. He was therefore compelled to conclude a peace with Saladin, not very advantageous to Christendom, and to return to Europe. But meeting with bad weather, he was driven on the coast of Histria; and, while endeavouring to travel through the country in the habit of a templar, was taken prisoner by Duke Leopold, of Austria, who became his enemy at the siege of Ptolemais. The duke sold him for forty thousand pounds to the emperor, Henry VI., who soon afterwards had a hundred thousand pounds for his ransom.

About the same period, Sultan Saladin, the most formidable enemy the Christians ever encountered, died; an event which caused Pope Celestine to prevail on the emperor, Henry VI., of Germany, to make a new expedition against the Turks, who were in consequence defeated; but the emperor's general, the Duke of Saxony, being killed, and the emperor himself dying soon afterwards, the Germans returned home without accomplishing the object of their expedition. They had no sooner departed than the Turks, in revenge, nearly drove the Christians from the Holy Land, and took all the strong towns which the Crusaders had gained, excepting Tyre and Ptolemais. In 1199, a fleet was fitted out at the instigation of Pope Innocent III. against the infidels. On this occasion, the Christians, notwithstanding their strenuous exertions, failed of taking Jerusalem, though several other important places were delivered to them.

In the year 1228, Frederic, Emperor of Germany, set out from Brundusium to Palestine, took Jerusalem, which the enemy had left in a desolate condition, and caused himself to be proclaimed king. But, after this conquest, he was obliged to return to his own country, where his presence was required. The Turks immediately assembled a prodigious army for regaining the Holy City, which they ultimately took, putting the German garrison to the sword, in the year 1234; since which time, the Christian powers, weary of these useless expeditions, have made no considerable effort to possess it.

The Christians were entirely driven from Palestine and Syria in the year 1291, about one hundred and ninety-two years after the capture of Jerusalem by Godfrey of Boulogne.

G.W.N.SHAKSPEARE.—A FRAGMENT

(For the Mirror.)The empty passions of the angry world,The loves of heroes, the despair of maids,The rage of kings, of beggars and of slaves,Shakspeare alone attun'd to song.—The rest essay'd.Laureate of bards! thyself unsungWould stamp us reckless.CYMBELINE.RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

REGAL TABLET

(Continued from page 111.)EDWARD IIbegan his reign 7th July, 1307, ended 25th Jan. 1327Popes.

Clement V., 1305.

John XXII., 1316.

Emperor of the East.

Andronicus II., 1283.

Emperors of the West.

Albert I., 1278.

Henry VII., 1308.

Frederic III., 1314.

France. Philip IV., 1285.

Louis X., 1314.

Charles IV. 1322.

Scotland. Robert Bruce, 1306.

EDWARD IIIbegan his reign 25th Jan. 1327, ended 21st June, 1377Popes.

John XXII., 1316.

Benedict XII., 1334.

Clement VI., 1342.

Innocent VI., 1352.

Urban V., 1362.

Gregory XI., 1370.

Emperors of the East.

Andronicus II., 1283.

Andronicus III., 1332.

John V., 1341.

John VI., 1355.

Emperors of the West.

Frederic III., 1314.

Louis IV., 1330.

Edward Baliol, 1332.

David II. (again), 1342.

Charles IV., 1347.

Robert II., 1370.

France.

Charles IV., 1322.

Philip VI., 1328.

John I., 1355.

Charles V., 1364.

Scotland.

Robert Bruce, 1306.

David II., 1330.

Edward Baliol, 1332.

David II. (again), 1342.

Robert II., 1370.

RICHARD IIbegan his reign 21st June, 1377, ended 29th Sept. 1399Popes.

Gregory XI., 1370.

Urban VI., 1378.

Boniface IX., 1389.

Emperors of the East.

John VI., 1355.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperors of the West.

Charles IV., 1347.

Weneslaus, 1378.

France.

Charles V., 1364.

Charles VI., 1380.

Scotland.

Robert II., 1370.

Robert III., 1390.

(House of Lancaster.)HENRY IVbegan his reign 29th Sept. 1399, ended 20th March, 1413

Popes.

Boniface IX., 1389.

Innocent VII., 1404.

Emperors of the West.

Weneslaus, 1378.

Popes.

Gregory XII. 1406.

Alexander V. 1409.

John XXIII. 1410.

Emperor of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperors of the West.

Robert le Pet, 1400.

Sigismund, 1410.

France.

Charles VI., 1380.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

HENRY Vbegan his reign 20th March, 1413, ended 31st August, 1422Popes.

John XXIII. 1410.

Martin V., 1417.

Emperor of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperor of the West.

Sigismund, 1410.

France.

Charles VI., 1380.

Charles VII. 1422.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

HENRY VIbegan his reign 31st August, 1422, ended 4th March, 1461Popes.

Martin V., 1417.

Eugenius IV. 1431.

Nicholas V., 1447.

Galixus III. 1455.

Pius II., 1458.

Emperors of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

John VII., 1426.

Constantine III., last emperor 1448.

Emperors of the West.

Sigismund, 1410.

Albert II., 1438.

Frederic IV., 1440.

France.

Charles VII. 1422.

Louis XI., 1440.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

James I., 1424.

James II., 1437.

James III., 1440.

(House of York.)EDWARD IVbegan his reign 4th March, 1461, ended 9th April, 1483

Popes.

Pius II., 1458.

Paul II., 1464.

Sixtus IV., 1471.

Emperor of the West.

Frederic IV., 1440.

France.

Louis XI., 1440.

Scotland.

James III., 1440.

EDWARD Vbegan his reign 9th April, 1483, ended 22nd June, 1483Contemporaries as the last reignRICHARD IIIbegan his reign 22nd June, 1483, ended 22nd August, 1485

Contemporaries again, as before(Lancaster and York united.)

HENRY VIIbegan his reign 22nd August, 1485, ended 22nd April, 1509

Popes.

Innocent VIII., 1484.

Alexander VI. 1492.

Pius III., 1593.

Julius II., 1503.

Emperors of Germany.

Frederic IV., 1440.

Maximilian I. 1493.

France.

Charles VIII. 1485.

Louis XII., 1498.

Scotland.

James III., 1460.

James IV., 1489.

HENRY VIIIbegan his reign 22nd April, 1509, ended 28th Jan. 1547Popes.

Julius II., 1503.

Leo X., 1513.

Adrian VI., 1521.

Clement VII. 1523.

Paul III., 1534.

Emperors of Germany.

Maximilian I. 1493.

Charles V., 1519.

France.

Louis XII., 1498.

Francis I., 1515.

Henry II., 1547.

Scotland.

James IV., 1489.

James V., 1514.

Mary, 1542.

EDWARD VIbegan his reign 28th Jan. 1547, ended 6th July, 1553Popes.

Paul III., 1534.

Julius III., 1550.

Emperor of Germany.

Charles V., 1519.

France.

Henry II., 1547.

Scotland.

Mary, 1542.

MARYbegan her reign 6th July, 1553, ended 17th Nov. 1558Popes.

Julius III., 1550.

Marcellus II. 1555.

Paul IV., 1555.

Emperors of Germany.

Charles V., 1519.

Ferdinand, 1556.

And the other contemporary princes as in the last reignELIZABETHbegan her reign 17th Nov. 1558, ended 24th March, 1603

Popes.

Paul IV., 1555.

Pius IV., 1559.

Pius V., 1565.

Gregory XIII., 1572.

Sixtus V., 1585.

Urban VII., 1590.

Gregory XIV., 1590.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand I., 1556.

Maximilian II. 1564.

Rodolphus II. 1576.

France.

Henry II., 1547.

Francis II., 1559.

Charles IX., 1560.

Henry III., 1574.

Henry IV., 1589.

Popes.

Innocent IX. 1501.

Clement VIII., 1592.

Scotland.

Mary, 1542.

James VI., 1567.

Union of the two crowns of England and ScotlandJAMES Ibegan his reign 24th March, 1603, ended 27th March, 1625

Popes.

Clement VIII., 1592.

Leo IX., 1605.

Paul III., 1605.

Gregory XV. 1621.

Urban VIII. 1623.

Emperors of Germany.

Rodolphus II. 1576.

Matthias I., 1612.

Ferdinand III. 1619.

France.

Henry IV., 1589.

Louis XIII., 1610.

Spain & Portugal.

Philip III., 1507.

Philip IV., 1620.

Denmark.

Christian IV. 1588.

Sweden.

Sigismund, 1592.

Charles IX., 1606.

Gustavus II. 1611.

CHARLES Ibegan his reign 27th March, 1625, beheaded 30th Jan. 1648Popes.

Urban VIII. 1623.

Innocent X., 1644.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand II. 1619.

Ferdinand III. 1637.

France.

Louis XIII., 1610.

Louis XIV., 1643.

Spain & Portugal.

Philip IV., 1620.

Portugal only.

John IV., 1640.

Denmark.

Christian IV. 1583.

Frederic III. 1648.

Sweden.

Gustavus II. 1611.

Christiana, 1633.

The Inter-regnum and Usurpation underOLIVER CROMWELL,from 30th Jan. 1648, to 29th May, 1660

Popes.

Innocent X., 1644.

Alexander VII., 1655.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand III., 1637.

Leopold I., 1658.

France.

Louis XIV., 1643.

Spain.

Philip IV., 1620.

Portugal.

John IV., 1640.

Alonzo VI., 1656.

Denmark.

Frederic III. 1646.

Sweden.

Christiana, 1633.

Charles X., 1653.

*** The remainder of this very useful Tablet, which has been compiled by a Correspondent, expressly for our pages, will be found in the Supplement published with the present No.

THE ANECDOTE GALLERY

ANECDOTES OF A DIANA MONKEY

By Mrs. BowdichAn old ship companion of mine was a native of the Gold Coast, and was of the Diana species. He had been purchased by the cook of the vessel in which I sailed from Africa, and was considered his exclusive property. Jack's place then was close to the cabooce; but as his education progressed, he was gradually allowed an increase of liberty, till at last he enjoyed the range of the whole ship, except the cabin. I had embarked with more than a mere womanly aversion to monkeys, it was absolute antipathy; and although I often laughed at Jack's freaks, still I kept out of his way, till a circumstance brought with it a closer acquaintance, and cured me of my dislike. Our latitude was three degrees south, and we only proceeded by occasional tornadoes, the intervals of which were filled up by dead calms and bright weather; when these occurred during the day, the helm was frequently lashed, and all the watch went below. On one of these occasions I was sitting alone on the deck, and reading intently, when, in an instant, something jumped upon my shoulders, twisted its tale round my neck, and screamed close to my ears. My immediate conviction that it was Jack scarcely relieved me: but there was no help; I dared not cry for assistance, because I was afraid of him, and dared not obey the next impulse, which was to thump him off, for the same reason, I therefore became civil from necessity, and from that moment Jack and I entered into an alliance. He gradually loosened his hold, looked at my face, examined my hands and rings with the most minute attention, and soon found the biscuit which lay by my side. When I liked him well enough to profit by his friendship, he became a constant source of amusement. Like all other nautical monkeys, he was fond of pulling off the men's caps as they slept, and throwing them into the sea; of knocking over the parrots' cages to drink the water as it trickled along the deck, regardless of the occasional gripe he received; of taking the dried herbs out of the tin mugs in which the men were making tea of them; of dexterously picking out the pieces of biscuit which were toasting between the bars of the grate; of stealing the carpenter's tools; in short, of teasing every thing and every body: but he was also a first-rate equestrian. Whenever the pigs were let out to take a run on deck, he took his station behind a cask, whence he leaped on the back of one of his steeds as it passed. Of course the speed was increased, and the nails he stuck in to keep himself on, produced a squeaking: but Jack was never thrown, and became so fond of the exercise, that he was obliged to be shut up whenever the pigs were at liberty. Confinement was the worst punishment he could receive, and whenever threatened with that, or any other, he would cling to me for protection. At night, when about to be sent to bed in an empty hencoop, he generally hid himself under my shawl, and at last never suffered any one but myself to put him to rest. He was particularly jealous of the other monkeys on board, who were all smaller than himself, and put two out of his way. The first feat of the kind was performed in my presence: he began by holding out his paw, and making a squeaking noise, which the other evidently considered as an invitation; the poor little thing crouched to him most humbly; but Jack seized him by the neck, hopped off to the side of the vessel, and threw him into the sea. We cast out a rope immediately, but the monkey was too frightened to cling to it, and we were going too fast to save him by any other means. Of course, Jack was flogged and scolded, at which he was very penitent; but the deceitful rogue, at the end of three days, sent another victim to the same destiny. But his spite against his own race was manifested at another time in a very original way. The men had been painting the ship's side with a streak of white, and upon being summoned to dinner, left their brushes and paint on deck. Unknown to Jack, I was seated behind the companion door, and saw the whole transaction; he called a little black monkey to him, who, like the others, immediately crouched to his superior, when he seized him by the nape of the neck with one paw, took the brush, dripping with paint, with the other, and covered him with white from head to foot. Both the man at the helm and myself burst into a laugh, upon which Jack dropped his victim, and scampered up the rigging. The unhappy little beast began licking himself, but I called the steward, who washed him so well with turpentine, that all injury was prevented; but during our bustle Jack was peeping with his black nose through the bars of the maintop, apparently enjoying the confusion. For three days he persisted in remaining aloft; no one could catch him, he darted with such rapidity from rope to rope; at length, impelled by hunger, he dropped unexpectedly from some height on my knees, as if for refuge, and as he had thus confided in me, I could not deliver him up to punishment.