The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 323, July 19, 1828

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 12, No. 323, July 19, 1828

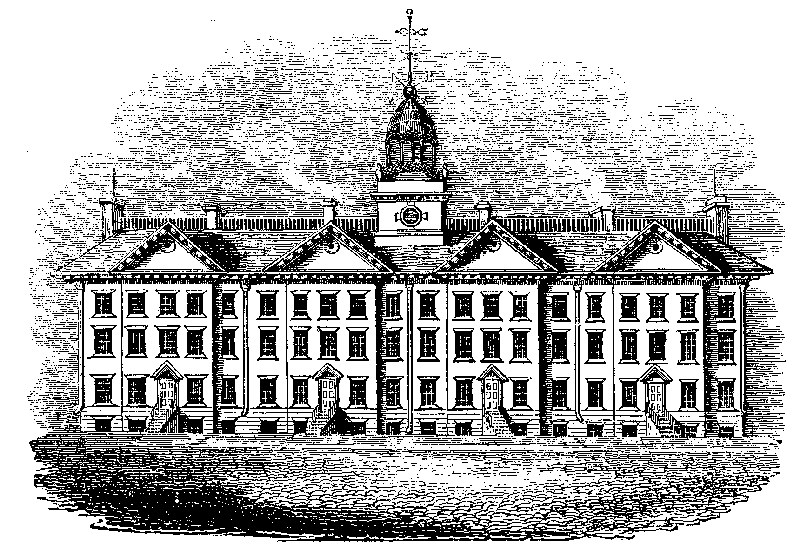

COLOMBIA COLLEGE, NEW-YORK

“It is intended that a large academy be erected, capable of containing nine thousand seven hundred and forty-three persons: which, by modest computation, is reckoned to be pretty near the current number of wits in this island,”

–Swift’s Tale of a Tub.

Instruction, manners, mysteries, and trades.

One college is almost completed within her radius, and will be opened in a few weeks; whilst munificent subscriptions are pouring in from all quarters of the empire, towards the endowment of a second. We have hitherto been silent spectators of these grand strides in the intellectual advancement of our country; but we have not, on that account, been less sensible of the important benefits which they are calculated to work in her social scheme, and in

The nurture of her youth, her dearest pledge.

We are not of those who would (even were Newton’s theory practicable) compress the world into a nutshell, or neglect “aught toward the general good;” and one of our respected correspondents, who doubtless participates in these cosmopolitan sentiments, has furnished us with the original of the above view of COLOMBIA COLLEGE; seeing that this, like the universities of our own country, is equally important to “Prince Posterity,” and accordingly we proceed with our correspondent’s description.

Colombia College, in the city of New York (of the principal building of which the annexed sketch is a correct representation) may be ranked among the chief seminaries of learning in America. It was principally founded by the voluntary contributions of the inhabitants of the province, assisted by the general assembly and corporation of Trinity Church, in 1754; at which time it was called King’s College.

A royal charter, and grant of money, was obtained, incorporating a number of gentlemen therein mentioned, by the name of “The Governors of the College of the province of New York, in the City of New York;” and granting to them and their successors for ever, among various other rights and privileges, the power of conferring such degrees as are usually conferred by the English universities. The president and members to be of the church of England, and the form of prayer used to be collected from the Liturgy of the church of England.

Since the revolution, the legislature passed an act, constituting twenty-one gentlemen, (of whom were the governor and lieutenant-governor for the time being,) a body corporate and politic, by the name of “the Regents of the University of the state of New York.” They were entrusted with the care of the literature of the state, and a power to grant charters for erecting colleges and academies throughout the state.

It received the name of Colombia College in 1787; when by an act of the legislature, it was placed under the care of twenty-four gentlemen, styled, “the trustees of the Colombian College,” who possessed the same powers as those of King’s College.

In 1813, the College of Physicians and the Medical School were united; and the academical and medical departments are together styled “The University of New York.” It is now well endowed and liberally patronized by the legislature of the state. The College consists of two handsome stone edifices, but the view given is but one-third of the originally intended structure, and contains a chapel, hall, library of 5,000 volumes, museum, anatomical theatre, and school for experimental philosophy.

The Medical College is a large, brick building, containing an anatomical museum, chemical laboratory, mineralogical cabinet, museum of natural history, and a botanical garden, and nine medical professors. Every student pays to each professor from 15 to 25 dollars per course.

There are also professors of mathematics, natural philosophy, history, ancient and modern languages, logic, &c. The number of students in 1818 was 233, but it has now greatly increased. As many in each year as finish their course of study, walk in procession with the other students and all the professors, preceded by a band of music to St. Paul’s church, where they deliver orations in English and Latin before a crowded assembly. This is called “a commencement.”

The situation is about 150 yards from the Hudson, of which, and the surrounding country it commands an extensive view. The whole is enclosed by a stone wall, with an area of several acres, interspersed with gravel walks, green plats, and full-grown trees.

BETA.

Note.—All our readers may not be aware that the remains of Two Literary Colleges still exist in London: Gresham College and Sion College—or we should say of one of them. The first was founded and endowed by that excellent citizen Sir Thomas Gresham. He was much opposed by the university of Cambridge, which endeavoured to prevent the establishment of a rival institution. (This was two centuries and a half ago.) He devised by will, his house in Bishopsgate street, to be converted into habitations and lecture-rooms for seven professors or lecturers on seven liberal sciences, who were to receive a salary out of the revenues of the Royal Exchange. Gresham College was subsequently converted into the modern general excise-office; but the places are still continued, with a double salary for the loss of apartments, and the lectures are delivered gratuitously twice a day in a small room in the Royal Exchange, during term-time. The will of the founder has not, however, been actually carried into execution. As we hate “solemn farce” and “ignorance in stilts,” we hope “scrutiny will not be stone blind” in this matter. A more useful man than Sir Thomas Gresham is not to be found in British biography, and it is painful to see his good intentions frustrated.

Sion College is situated near London Wall, to the south of Fore-street. It was founded in 1623 by the rector of St. Dunstan’s in the west, for the London clergy. The whole body of rectors and vicars within the city are fellows of this college, and all the clergy in and near the metropolis may have free access to its extensive and valuable library.

SUPERSTITIONS ON THE WEATHER

From Sir H. Davy’s Salmonia; or, Days of Fly-fishing. (In Conversations.)POIETES, a Tyro in Fly-fishing.—PHYSICUS, an uninitiated Angler, fond of inquiries in natural history, &c.—HALIEUS, an accomplished fly-fisher.—ORNITHER, a sporting gentleman.

Poietes. I hope we shall have another good day to-morrow, for the clouds are red in the west.

Physicus. I have no doubt of it, for the red has a tint of purple.

Halieus. Do you know why this tint portends fine weather?

Phys. The air, when dry, I believe, refracts more red, or heat-making rays; and as dry air is not perfectly transparent, they are again reflected in the horizon. I have generally observed a coppery or yellow sun-set to foretell rain; but, as an indication of wet weather approaching, nothing is more certain than a halo round the moon, which is produced by the precipitated water; and the larger the circle, the nearer the clouds, and consequently the more ready to fall.

Hal. I have often observed that the old proverb is correct—

A rainbow in the morning is the shepherd’s warning:A rainbow at night is the shepherd’s delight.Can you explain this omen?

Phys. A rainbow can only occur when the clouds containing or depositing the rain are opposite to the sun,—and in the evening the rainbow is in the east, and in the morning in the west; and as our heavy rains in this climate are usually brought by the westerly wind, a rainbow in the west indicates that the bad weather is on the road, by the wind, to us; whereas the rainbow in the east proves that the rain in these clouds is passing from us.

Poiet. I have often observed, that when the swallows fly high, fine weather is to be expected or continued; but when they fly low, and close to the ground, rain is almost surely approaching. Can you account for this?

Hal. Swallows follow the flies and gnats, and flies and gnats usually delight in warm strata of air; and as warm air is lighter, and usually moister, than cold air, when the warm strata of air are high, there is less chance of moisture being thrown down from them by the mixture with cold air; but when the warm and moist air is close to the surface, it is almost certain that, as the cold air flows down into it, a deposition of water will take place.

Poiet. I have often seen sea-gulls assemble on the land, and have almost always observed that very stormy and rainy weather was approaching. I conclude that these animals, sensible of a current of air approaching from the ocean, retire to the land to shelter themselves from the storm.

Ornither. No such thing. The storm is their element; and the little petrel enjoys the heaviest gale, because, living on the smaller sea-insects, he is sure to find his food in the spray of a heavy wave—and you may see him flitting above the edge of the highest surge. I believe that the reason of this migration of sea-gulls, and other sea-birds, to the land, is their security of finding food; and they may be observed, at this time, feeding greedily on the earth-worms and larva, driven out of the ground by severe floods: and the fish, on which they prey in fine weather in the sea, leave the surface and go deeper in storms. The search after food is the principal cause why animals change their places. The different tribes of the wading birds always migrate when rain is about to take place; and I remember once, in Italy, having been long waiting, in the end of March, for the arrival of the double snipe in the Campagna of Rome, a great flight appeared on the 3rd of April, and the day after heavy rain set in, which greatly interfered with my sport. The vulture, upon the same principle, follows armies; and I have no doubt that the augury of the ancients was a good deal founded upon the observation of the instincts of birds. There are many superstitions of the vulgar owing to the same source. For anglers, in spring, it is always unlucky to see single magpies,—but two may be always regarded as a favourable omen; and the reason is, that in cold and stormy weather, one magpie alone leaves the nest in search of food, the other remaining sitting upon the eggs or the young ones; but when two go out together, it is only when the weather is warm and mild, and favourable for fishing.

Poiet. The singular connexions of causes and effects, to which you have just referred, make superstition less to be wondered at, particularly amongst the vulgar; and when two facts naturally unconnected, have been accidentally coincident, it is not singular that this coincidence should have been observed and registered, and that omens of the most absurd kind should be trusted in. In the west of England, half a century ago, a particular hollow noise on the sea-coast was referred to a spirit or goblin, called Bucca, and was supposed to foretell a shipwreck: the philosopher knows that sound travels much faster than currents in the air, and the sound always foretold the approach of a very heavy storm, which seldom takes place on that wild and rocky coast without a shipwreck on some part of its extensive shores, surrounded by the Atlantic.

Phys. All the instances of omens you have mentioned are founded on reason; but how can you explain such absurdities as Friday being an unlucky day, the terror of spilling salt, or meeting an old woman? I knew a man of very high dignity, who was exceedingly moved by these omens, and who never went out shooting without a bittern’s claw fastened to his button-hole by a riband, which he thought ensured him good luck.

Poiet. These, as well as the omens of death-watches, dreams, &c., are for the most part founded upon some accidental coincidences; but spilling of salt, on an uncommon occasion, may, as I have known it, arise from a disposition to apoplexy, shown by an incipient numbness in the hand, and may be a fatal symptom; and persons, dispirited by bad omens, sometimes prepare the way for evil fortune; for confidence in success is a great means of ensuring it. The dream of Brutus, before the field of Pharsalia, probably produced a species of irresolution and despondency, which was the principal cause of his losing the battle: and I have heard that the illustrious sportsman to whom you referred just now, was always observed to shoot ill, because he shot carelessly, after one of his dispiriting omens.

Hal. I have in life met with a few coincidences or by natural connexions; and I have known minds of a very superior class affected by them,—persons in the habit of reasoning deeply and profoundly.

Phys. In my opinion, profound minds are the most likely to think lightly of the resources of human reason; and it is the pert, superficial thinker, who is generally strongest in every kind of unbelief. The deep philosopher sees chains of causes and effects so wonderfully and strangely linked together, that he is usually the last person to decide upon the impossibility of any two series of events being independent of each other; and in sciences, so many natural miracles, as it were, have been brought to light,—such as the fall of stones from meteors in the atmosphere, the disarming of a thunder-cloud by a metallic point, the production of fire from ice by a metal white as silver, and referring certain laws of motion of the sea to the moon,—that the physical inquirer is seldom disposed to assert, confidently, on any abstruse subjects belonging to the order of natural things, and still less so on those relating to the more mysterious relations of moral events and intellectual natures.

DEVIL’S HOLE, KIRBY STEPHEN

(For the Mirror.)At about three quarters of a mile east of Kirby Stephen, Westmoreland, is a bridge of solid rock, known by the name of Staincroft Bridge or Stonecroft Bridge, under which runs a small but fathomless rivulet. The water roars and gushes through the surrounding rocks and precipices with such violence, as almost to deafen the visitor. Three or four yards from the bridge is an immense abyss, where the waters “incessantly roar,” which goes by the name of Devil’s Hole; the tradition of which is, that two lovers were swallowed up in this frightful gulf. The neighbouring peasants tell a tale of one Deville, a lover, who, through revenge, plunged his fair mistress into these waters, and afterwards followed her. How far this story may get belief, I know not; but such they aver is the truth, while they mournfully lament the sad affair.—They point out a small hole in the bank where you may hear the waters dashing with fury against the projecting rocks. This, some imagine to be the noise of infernal spirits, who have taken up their abode in this tremendous abyss; while others persist in their opinion, that the lover’s name was Deville, and that it retains his name to this day, in commemoration of the horrid deed.

I have seen, and taken a view of the frightful place, which may rather be imagined than described. One part of the water was formerly so narrow, that a wager was laid by a gentleman that he could span it with the thumb and little finger, and which he would have accomplished, but his adversary, getting up in the night time, chipped a piece off the rock with a hammer, and thus won the wager. It is now, however, little more than from a foot and a half, to two feet broad, excepting at the falls and Devil’s Hole. The water runs into the Eden at the distance of about a mile or two from Staincroft Bridge. Trout are caught with the line and net in great quantities, and are particularly fine here.

W.H.H.ANECDOTES OF A TAMED PANTHER

BY MRS. BOWDICH[Mrs. Bowdich is the widow of Mr. Thomas Edward Bowdich, who fell a victim to his enterprize in exploring the interior of Africa, in 1824. Mr. B. was a profound classic and linguist and member of several learned societies in England and abroad. In 1819 he published, in a quarto volume, his “Mission to Ashantee,” a work of the highest importance and interest. Mrs. B., whose pencil has furnished embellishments for her husband’s literary productions, has published “Excursions to Madeira, &c.,” and this amiable and accomplished lady has now in course of publication, a work on the Fresh-water Fishes of Great Britain.—The subsequent anecdotes are of equal interest to the student of natural history and the general reader, especially as they exhibit the habits and disposition of the Panther in a new light. The Ounce, a variety of the Panther is, however, easily tamed and trained to the chase of deer, the gazelle, &c.—for which purpose it has long been employed in the East, and also during the middle ages in Italy and France.—Mr. Kean, the tragedian, a few years since, had a tame Puma, or American Lion, which he kept at his house in Clarges-street, Piccadilly, and frequently introduced to large parties of company.—ED.]

I am induced to send you some account of a panther which was in my possession for several months. He and another were found when very young in the forest, apparently deserted by their mother. They were taken to the king of Ashantee, in whose palace they lived several weeks, when my hero, being much larger than his companion, suffocated him in a fit of romping, and was then sent to Mr. Hutchison, the resident left by Mr. Bowdich at Coomassie. This gentleman, observing that the animal was very docile, took pains to tame him, and in a great measure succeeded. When he was about a year old, Mr. Hutchison returned to Cape Coast, and had him led through the country by a chain, occasionally letting him loose when eating was going forward, when he would sit by his master’s side, and receive his share with comparative gentleness. Once or twice he purloined a fowl, but easily gave it up to Mr. Hutchison, on being allowed a portion of something else. The day of his arrival he was placed in a small court, leading to the private rooms of the governor, and after dinner was led by a thin cord into the room, where he received our salutations with some degree of roughness, but with perfect good-humour. On the least encouragement he laid his paws upon our shoulders, rubbed his head upon us, and his teeth and claws having been filed, there was no danger of tearing our clothes. He was kept in the above court for a week or two, and evinced no ferocity, except when one of the servants tried to pull his food from him; he then caught the offender by the leg, and tore out a piece of flesh, but he never seemed to owe him any ill-will afterwards. He one morning broke his cord, and, the cry being given, the castle gates were shut, and a chase commenced. After leading his pursuers two or three times round the ramparts, and knocking over a few children by bouncing against them, he suffered himself to be caught, and led quietly back to his quarters, under one of the guns of the fortress.

By degrees the fear of him subsided, and orders having been given to the sentinels to prevent his escape through the gates, he was left at liberty to go where he pleased, and a boy was appointed to prevent him from intruding into the apartments of the officers. His keeper, however, generally passed his watch in sleeping; and Saï, as the panther was called, after the royal giver, roamed at large. On one occasion he found his servant sitting on the step of the door, upright, but fast asleep, when he lifted his paw, gave him a blow on the side of his head which laid him flat, and then stood wagging his tail, as if enjoying the mischief he had committed. He became exceedingly attached to the governor, and followed him every-where like a dog. His favourite station was at a window of the sitting-room, which overlooked the whole town; there, standing on his hind legs, his fore paws resting on the ledge of the window, and his chin laid between them, he appeared to amuse himself with what was passing beneath. The children also stood with him at the window; and one day, finding his presence an encumbrance, and that they could not get their chairs close, they used their united efforts to pull him down by the tail. He one morning missed the governor, who was settling a dispute in the hall, and who, being surrounded by black people, was hidden from the view of his favourite. Saï wandered with a dejected look to various parts of the fortress in search of him; and, while absent on this errand, the audience ceased, the governor returned to his private rooms, and seated himself at a table to write. Presently he heard a heavy step coming up the stairs, and, raising his eyes to the open door, he beheld Saï. At that moment he gave himself up for lost, for Saï immediately sprang from the door on to his neck. Instead, however, of devouring him, he laid his head close to the governor’s, rubbed his cheek upon his shoulder, wagged his tail, and tried to evince his happiness. Occasionally, however, the panther caused a little alarm to the other inmates of the castle, and the poor woman who swept the floors, or, to speak technically, the pra-pra woman, was made ill by her fright. She was one day sweeping the boards of the great hall with a short broom, and in an attitude nearly approaching to all-fours, and Saï, who was hidden under one of the sofas, suddenly leaped upon her back, where he stood in triumph. She screamed so violently as to summon the other servants, but they, seeing the panther, as they thought, in the act of swallowing her, one and all scampered off as quickly as possible; nor was she released till the governor, who heard the noise, came to her assistance. Strangers were naturally uncomfortable when they saw so powerful a beast at perfect liberty, and many were the ridiculous scenes which took place, they not liking to own their alarm, yet perfectly unable to retain their composure in his presence.

This interesting animal was well fed twice every day, but never given any thing with life in it. He stood about two feet high, and was of a dark yellow colour, thickly spotted with black rosettes, and from the good feeding and the care taken to clean him, his skin shone like silk. The expression of his countenance was very animated and good-tempered, and he was particularly gentle to children; he would lie down on the mats by their side when they slept, and even the infant shared his caresses, and remained unhurt. During the period of his residence at Cape Coast, I was much occupied by making arrangements for my departure from Africa, but generally visited my future companion every day, and we, in consequence, became great friends before we sailed. He was conveyed on board the vessel in a large, wooden cage, thickly barred in the front with iron. Even this confinement was not deemed a sufficient protection by the canoe men,1 who were so alarmed at taking him from the shore to the vessel, that, in their confusion, they dropped cage and all into the sea. For a few minutes I gave up my poor panther as lost, but some sailors jumped into a boat belonging to the vessel, and dragged him out in safety. The beast himself seemed completely subdued by his ducking, and as no one dared to open his cage to dry it, he rolled himself up in one corner, nor roused himself till after an interval of some days, when he recognised my voice. When I first spoke, he raised his head, held it on one side, then on the other, to listen; and when I came fully into his view, he jumped on his legs, and appeared frantic; he rolled himself over and over, he howled, he opened his enormous jaws and cried, and seemed as if he would have torn his cage to pieces. However, as his violence subsided, he contented himself with thrusting his paws and nose through the bars of the cage, to receive my caresses.

The greatest treat I could bestow upon my favourite was lavender water. Mr. Hutchison had told me that, on the way from Ashantee, he drew a scented handkerchief from his pocket, which was immediately seized on by the panther, who reduced it to atoms; nor could he venture to open a bottle of perfume when the animal was near, he was so eager to enjoy it. I indulged him twice a week by making a cup of stiff paper, pouring a little lavender water into it, and giving it to him through the bars of his cage: he would drag it to him with great eagerness, roll himself over it, nor rest till the smell had evaporated. By this I taught him to put out his paws without showing his nails, always refusing the lavender water till he had drawn them back again; and in a short time he never, on any occasion, protruded his claws when offering me his paw.