The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 276, October 6, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 276, October 6, 1827

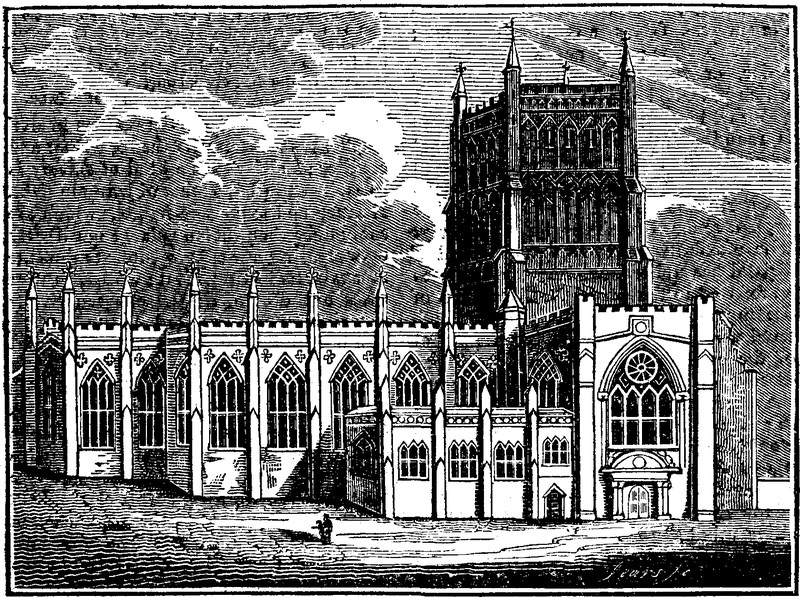

BRISTOL CATHEDRAL

The cathedral of Bristol is one of the most interesting relics of monastic splendour which have been spared from the wrecks of desolation and decay. It is dedicated to the holy and undivided Trinity, and is the remains of an abbey or monastery of great magnificence, which was dedicated to St. Augustine. The erection of this monastery was begun in 1140, and was finished and dedicated in 1148, according to the inscription on the tomb of the founder, Robert Fitzharding, the first lord of Berkeley, who, together with others of that illustrious family, are enshrined within these walls. It was also denominated the monastery of the black regular canons of the order of Saint Victor, who are mentioned by Leland as the black canons of St. Augustine within the city walls. By some historians, Fitzharding is represented as an opulent citizen of Bristol; but generally as a younger son or grandson of the king of Denmark, and as the youthful companion of Henry II., who, betaking himself from the sunshine of royal friendship, became a canon of the monastery he himself had founded. In this congenial solitude he died in 1170, aged 75. Such is the outline of the foundation of this structure, and it is one of the most attractive episodes of the early history of England; for the circumstance of a noble exchanging the gilded finery of a court, and the gay companionship of his prince, for the gloomy cloisters of an abbey, and the ascetic duties of monastic life, bespeaks a degree of resolution and self-control which was more probably the result of sincere conviction than of momentary caprice.

The present cathedral is represented to have been merely the church of the monastery, which was entirely rebuilt in the commencement of the fourteenth century. The style of architecture in the different parts of this cathedral is accurately discriminated in the following account from the pen of Bishop Littleton, F.S.A.:—"The lower parts of the chapter house walls," says he, "together with the door-way and columns at the entrance of the chapter-house, may be pronounced to be of the age of Stephen, or rather prior to his reign, being fine Saxon architecture. The inside walls of the chapter-house have round ornamental arches intersecting each other. The cathedral appears to be of the same style of building throughout, and in no part older than Edward the First's time, though some writers suppose the present fabric was begun in king Stephen's time; but not a single arch, pillar, or window agrees with the mode which prevailed at that time. The great gateway leading into the College Green is round-arched, with mouldings richly ornamented in the Saxon taste." From this account it appears probable that the chapter-house and gateway are all the present remains of the ancient monastery. The mutilations which the cathedral of Bristol has undergone, are not entirely to be referred to the era of the dissolution of the monasteries, since this structure suffered very considerably during the period of the civil wars. The ruthless soldiers discovered their barbarism by violating the sacred tombs of the dead, and by offering every indignity which they supposed would be considered a profanation of the places which the piety of their ancestors consecrated to religion. At such instances of the violence of civil factions, the sensitive mind shudders with disgust.

The cathedral of Bristol is rich in monumental tributes to departed worth. Among them is an elegant monument, by Bacon, to Mrs. Elizabeth Draper, the Eliza of Sterne; and the classical tomb of the Hendersons. Here, too, rests Lady Hesketh, the friend of Cowper; Powell, of Covent Garden Theatre; besides branches of the Berkeley family, and various abbots.

The bishopric of Bristol is the least wealthy ecclesiastical promotion which confers the dignity of a mitre. Its revenue is generally stated to amount to no more than five or six hundred pounds per annum. In the list of bishops are Fletcher, father of the celebrated dramatist, the colleague of Beaumont; he attended Mary Queen of Scots on the Scaffold; Lake, one of the seven bishops committed to the Tower in the time of James I.; Trelawney, a familiar name in the events of 1688; Butler, who materially improved the episcopal palace of Bristol; Conybeare and Newton, names well known in literary history; with the erudite Warburton, whose name occurs in the list of deans of Bristol.

DEBTOR AND CREDITOR. 1

The time is out of joint.

—Hamlet.A man of my profession never counterfeits, till he lays hold upon a debtor and says he rests him: for then he brings him to all manner of unrest.

—The Bailiff, in 'Every Man in his Humour.'Run not into debt, either for wares sold or money borrowed; be content to want things that are not of absolute necessity, rather than to run up the score: such a man pays at the latter a third part more than the principal comes to, and is in perpetual servitude to his creditors;

lives uncomfortably; is necessitated to increase his debts to stop his creditors' mouths; and many times falls into desperate courses.

SIR M. HALE."The greatest of all distinctions in civil life," says Steele, "is that of debtor and creditor;" although no kind of slavery is so easily endured, as that of being in debt. Luxury and expensive habits, which are commonly thought to enlarge our liberty by increasing our enjoyments, are thus the means of its infringement; whilst, in nine cases out of ten, the lessons taught by this rigid experience lead to the bending and breaking of our spirits, and the unfitting of us for the rational pleasures of life. All ranks of mankind seem to fall into this fatal error, from the voluptuous Cleopatra to the needy philosopher, who doles out a mealsworth of morality for his fellow-creatures, and who would fain live according to his own precepts, had he not exhausted his means in the acquisition of his experience.

I blush to confess, that I have often thought the habit of debt to be our national inheritance—from that bugbear of out-of-place men, the Sinking Fund, to the parish-clerk, who mortgages his fees at the chandler's; and that my countrymen seem to have resolved to increase their own enjoyments at the expense of posterity, with whose provision, even Swift thinks we have no concern. Again; I have thought that we are apt to over-rate our national advancement, by supposing the present race to be wiser than the previous one, without once looking into our individual contributions to this state of enlightenment. Proud as we are of this distinction in the social scale, we can record few instances of contemporary genius, and we are bound to confess that men are not a whit the better in the present than in the previous generation. Thus we hoodwink each other till social outrages become every-day occurrences, and every thing but sheer violence is protected by its frequency; and in this manner we consent to compromise our happiness, and then affect to be astonished at its scarcity. In the later ages of the world, men have learned to temporize with principles, and to sacrifice, at the shrine of passing interest, as much real virtue as would bear them harmless throughout life. Hence, of what more avail is the virtue of the Roman fathers, or are the amiable friendships of Scipio and Lelius, than as so many amusing fictions to exercise the imaginations of schoolmen in drawing outlines of character, which experience does not finish. Friends, like certain flowers, bloom around us in the sunshine of success; but at night-fall or at the approach of storms, they shut up their hearts; and thus, poor victims being rifled of their mind's content, with their little string of enjoyments broken up for ever, are abandoned to the pity or scorn of bystanders. It is impossible to reflect for a moment on such a crisis, without dropping a tear for the self-created infirmities of man: but there are considerations at which he shudders, and which he would rather varnish over with the sophistry of his refinement, and the fallacies of self-conceit.

I fear that I am breaking my rule in not confining myself to a few shades of debt and conscience, with a view of determining how far they are usually reconciled among us. The task may not prove altogether fruitless; notwithstanding, to find honest men, would require the lantern of Diogenes, and perhaps turn out like Gratiano's wheat.

In our youthful days, we all remember to have read a pithy string of Maxims by Dr. Franklin; and we are accustomed to admire the pertinence of their wit,—but here their influence too often terminates. Since Franklin's time, the practice of getting into debt has become more and more easy, notwithstanding men have become more wary. Goldsmith, too, gives us a true picture of this habit in his scene with Mr. Padusoy, the mercer, a mode which has been found to succeed so well since his time, that, with the exception of a few short-cuts by sharpers and other proscribed gentry, little amendment has been made. Profuseness on the part of the debtor will generally be found to beget confidence on that of the creditor; and, in like manner, diffidence will create mistrust, and mistrust an entire overthrow of the scheme. An unblushing front, and the gift of non chalance, are therefore the best qualifications for a debtor to obtain credit, while poor modesty will be starved in her own littleness. In vain has Juvenal protested—"Fronti nulla fides;" and have the world been amused with anecdotes of paupers dying with money sewed up in their clothes: appearance and assumed habits are still the handmaids to confidence; and so long as this system exists, the warfare of debtor and creditor will be continued. Procrastination will be found to be another furtherance of the system, inasmuch as it is too evident throughout life that men are more apt to take pleasure "by the forelock," than to calculate its consequence. In this manner, men of irregular habits anticipate and forestal every hour of their lives, and pleasure and pain alternate, till pain, like debt, accumulates, and sinks its patient below the level of the world. Economy and forecast do not enter into the composition of such men, nor are such lessons often felt or acknowledged, till custom has rendered the heart unfit for the reception of their counsels. It is too frequently that the neglect of these principles strikes at the root of social happiness, and produces those lamentable wrecks of men—those shadows of sovereignty, which people our prisons, poor-houses, and asylums. Genius, with all her book-knowledge, is not exempt from this failing; but, on the contrary, a sort of fatality seems to attend her sons and daughters, which tarnishes their fame, and often exposes them to the brutish attacks of the ignorant and vulgar. Wits, and even philosophers, are among this number; and we are bound to acknowledge, that, beyond the raciness of their writings, there is but little to admire or imitate in the lives of such men as Steele, Foote, or Sheridan. It is, however, fit that principle should be thus recognised and upheld, and that any dereliction from its rules should be placed against the account of such as enjoy other degrees of superiority, and allowed to form an item in the scale of their merits.

(To be concluded in our next.)AN ENGLISHMAN'S PRAYER

Grant, righteous Heaven, however cast my fateOn social duties or in toils of state,Whether at home dispensing equal laws,Or foremost struggling for the world's applause,As neighbour, husband, brother, sire, or son,In every work, accomplished or begun,Grant that, by me, thy holy will be done.When false ambition tempts my soul to rise,Teach me her proffer'd honours to despise,Though chains or poverty await the just,Though villains lure me to betray my trust,Unmoved by wealth, unawed by tyrant, mightStill let me steadily pursue the right,Hold fast my plighted faith, nor stoop to giveFor lengthen'd life, the only cause to live.ITALY

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)SIR,—Is your correspondent (see the MIRROR of the 15th of September) quite right in asserting that Italy has invariably retained the same name from its first settlement? or would the fact be singular if true? Virgil, in his first book of the Æneid, implies that it had at least two names before that of Italy. "Ænotrii coluere viri;" "Hesperiam graii cognomine dicunt;" "Itali ducis de nomine." His works are not at hand, so that I cannot specify the line; but the passage is repeated three or four times in the course of the poem, and the reference, therefore, to it is peculiarly easy.

In other places, as you may remember, he gives it the appellation of "Ausonia."

Now as to the singularity of the circumstance, supposing it were otherwise, to what does it amount but this: that when Italian power extended over the countries of Europe, Italian names were given them; that as this power declined, these names as naturally fell into disuse; and the different nations, actuated severally by a spirit of independence or of caprice, recurred to their own or foreign tongues for the designation of their territory. While at Rome itself, which, though often suffering from the calamities of war, still retained a considerable share of influence, the inhabitants adhered to their native dialect, and the same city which had been the birth-place and cradle of the infant language was permitted to become its sanctuary at last.

Y.M.SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

ELISE

(By L.E.L.)O Let me love her! she has past Into my inmost heart—A dweller on the hallowed ground Of its least worldly part;Where feelings and where memories dwell Like hidden music in the shell.She was so like the forms that float On twilight's hour to me,Making of cloud-born shapes and thoughts A dear reality;As much a thing of light and air As ever poet's visions were.I left smoke, vanities, and cares, Just far enough behind,To dream of fairies 'neath the moon, Of voices on the wind,And every fantasy of mine Was truth in that sweet face of thine.Her cheek was very, very pale, Yet it was still more fair;Lost were one half its loveliness, Had the red rose been there:But now that sad and touching graceMade her's seem like an angel's face.The spring, with all its breath and bloom, Hath not so dear a flower,As the white lily's languid head Drooping beneath the shower;And health hath ever waken'd lessOf deep and anxious tenderness.And O thy destiny was love, Written in those soft eyes;A creature to be met with smiles. And to be watch'd with sighs;A sweet and fragile blossom, madeTo be within the bosom laid.And there are some beneath whose touch The coldest hearts expand,As erst the rocks gave forth their tears Beneath the prophet's hand;And colder than that rock must beThe heart that melted not for thee.Thy voice—thy poet lover's song Has not a softer tone;Thy dark eyes—only stars at night Such holy light have known;And thy smile is thy heart's sweet sign,So gentle and so feminine.I feel, in gazing on thy face, As I had known thee long;Thy looks are like notes that recall Some old remembered songBy all that touches and endears,Lady, I must have loved thee years.Literary Gazette.COLONEL GEORGE HANGER

Dining on one occasion at Carlton-house, it is said that, after the bottle had for some time circulated, his good-humoured volubility suddenly ceased, and he seemed for a time to be wholly lost in thought. While he "chewed the cud" in this ruminating state, his illustrious host remarked his very unusual quiescency, and interrupted it by inquiring the subject of his meditation. "I have been reflecting, Sir," replied the colonel, "on the lofty independence of my present situation. I have compromised with my creditors, paid my washerwoman, and have three shillings and sixpence left for the pleasures and necessities of life," exhibiting at the same time current coin of the realm, in silver and copper, to that amount, upon the splendid board at which he sat.

Having occasion to express his gratitude to his friend and patron for his nomination to a situation under government (which, had he been prudent, might have sufficed for genteel support), it is said that the royal personage condescended to observe, on the colonel's expatiating on the advantages of his office, that "now he was rich, he would so far impose upon his hospitality as to dine with him;" at the same time insisting on the repast being any thing but extravagant. "I shall give your royal highness a leg of mutton, and nothing more, by G–," warmly replied the gratified colonel, in his plain and homely phrase. The day was nominated, and the colonel had sufficient time to recur to his budget and bring his ways and means into action. Where is the sanguineless being whose hopes have never led him wrong? if such there be, the colonel was not one of those. Long destitute of credit and resources, he looked upon his appointment as the incontestable source of instant wealth, and he hesitated not to determine upon the forestalment of its profits to entertain the "first gentleman in England." But, alas! agents and brokers have flinty hearts. There were doubts (not of his word, for with creditors that he had never kept), but of the accidents of life, either naturally, or by one of those casualties he had depicted in the front of his book. In short, the day approached—nay, actually arrived, and his pockets could boast little more than the once vaunted half-crown and a shilling. Here was a state sufficient to drive one of less strength of mind to despair. As a friend, a subject, a man of honour, and one who prided himself upon a tenacious adherence to his word (when the aforesaid creditors were not concerned), he felt keenly all the horrors of his situation.

The day arrived, and etiquette demanded that the proper officer should examine and report upon the nature of the expected entertainment, a duty that had been deferred until a late hour of the day. Well was it that the confiding prince had not wholly dispensed with that form; for verily the said officer found the colonel, with a dirty scullion for his aide du camp, in active and zealous preparation for his royal visiter; his shirt sleeves tucked up, while he ardently basted the identical and solitary "leg of mutton" as it revolved upon the spit: potatoes were to be seen delicately insinuated into the pan beneath to catch the rich exudation of the joint; while several tankards of foaming ale, and what the French term "bread à discretion," announced that, in quantity, if not in quality, he had not been careless in providing for the entertainment of his illustrious guest. Although the colonel's culinary skill leaves no doubt that the leg of mutton would have sustained (according to Mr. Hunt's elegant phraseology) critical discussion on its intrinsic merits, or on its concoction; and although the dinner might have been endured by royalty (of whose homely appetite the ample gridiron at Alderman Combe's brewery then gave ample proof), yet his royal highness's poodles would assuredly have perspired through every pore at the very mention of what a certain nobleman used to term a "jig-hot;" so the feast was dispensed with, and due acknowledgment made for the evident proofs of hospitality which had been displayed.

After various vicissitudes of life and fortune, in Hanger's advanced age, a coronet became his, and it came opportunely; for he had at length learned experience, and knowing the value of the competence he had obtained, he resolved to enjoy it. He had had enough of fashion; and had proved all its allurements. So he took a small house in a part of earth's remoter regions, no great way from Somers' Town, near which stood a public-house he was fond of visiting, and there, as the price of his sanction, and in acknowledgment of his rank, a large chair by the fire-side was exclusively appropriated to the peer.

—New Monthly Magazine.ANECDOTES OF UGO FOSCOLO, THE ITALIAN POET

Foscolo was in person about the middle height, and somewhat thin, remarkably clean and neat in his dress,—although on ordinary occasions, he wore a short jacket, trousers of coarse cloth, a straw hat, and thick heavy shoes; the least speck of dirt on his own person, or on that of any of his attendants, seemed to give him real agony. His countenance was of a very expressive character, his eyes very penetrating, although they occasionally betrayed a restlessness and suspicion, which his words denied; his mouth was large and ugly, his nose drooping, in the way that physiognomists dislike, but his forehead was splendid in the extreme; large, smooth, and exemplifying all the power of thought and reasoning, for which his mind was so remarkable. It was, indeed, precisely the same as that we see given in the prints of Michael Angelo; he has often heard the comparison made, and by a nod assented to it. In his living, Foscolo was remarkably abstemious. He seldom drank more than two glasses of wine, but he was fond of having all he eat and drank of the very best kind, and laid out with great attention to order. He always took coffee immediately after dinner. His house,—I speak of the one he built for himself, near the Regent's Park,—was adorned with furniture of the most costly description; at one time he had five magnificent carpets, one under another, on his drawing-room, and no two chairs in his house were alike. His tables were all of rare and curious woods. Some of the best busts and statues (in plaster) were scattered through every apartment,—and on those he doated with a fervour scarcely short of adoration. I remember his once sending for me in great haste, and when I entered his library, I found him kneeling, and exclaiming, "beautiful, beautiful." He was gazing on the Venus de Medici, which he had discovered looked most enchanting, when the light of his lamp was made to shine upon it from a particular direction. On this occasion, he had summoned his whole household into his library, to witness the discovery which gave him so much rapture. In this state, continually exclaiming, "beautiful, beautiful," and gazing on the figure, he remained for nearly two hours.

He had the greatest dislike to be asked a question, which he did not consider important, and used to say, "I have three miseries—smoke, flies, and to be asked a foolish question."

His memory was one of the most remarkable. He has often requested me to copy for him (from some library) a passage, which I should find in such a page of such a book; and appeared as if he never forgot any thing with which he was once acquainted.

His conversation was peculiarly eloquent and impressive, such as to render it evident that he had not been over-rated as an orator, when in the days of his glory, he was the admiration of his country. I remember his once discoursing to me of language, and saying, "in every language, there are three things to be noticed,—verbs, substantives, and the particles; the verbs," holding out his hand, "are as the bones of these fingers; the substantives, the flesh and blood; but the particles are the sinews, without which the fingers could not move."

"There are," said he to me, once, "three kinds of writing—diplomatic, in which you do not come to a point, but write artfully, and not to show what you mean; attorney, in which you are brief; and enlarged, in which you spread and stretch your thoughts."

I have said that his cottage, (built by himself,) near the Regent's Park, was very beautiful. I remember his showing me a letter to a friend, in which were the following passages:—After alluding to some pecuniary difficulties, he says, "I can easily undergo all privations, but my dwelling is always my workshop, and often my prison, and ought not to distress me with the appearance of misery, and I confess, in this respect, I cannot be acquitted of extravagance."