По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

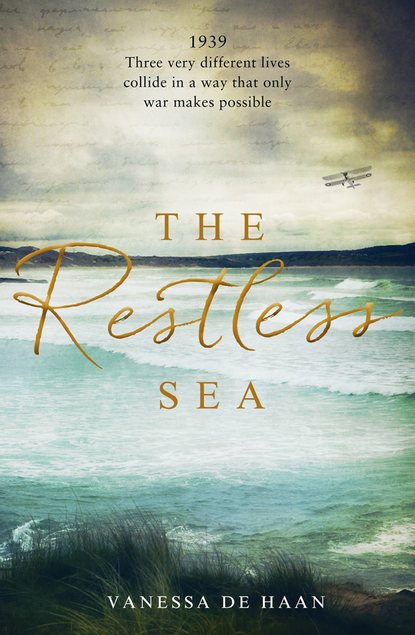

The Restless Sea

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They drop anchor about seven hundred yards from the older ship. The heavy chain rushes out of the hawsepipe with a rattle and a splash, and plummets to the bottom of the harbour. The men get ready to relax. Some prepare for a night of cards or building models or listening to the radio. Others will go ashore to stretch their legs. Charlie is surprised to find a letter delivered into his hand. Hope leaps in his chest like a fish. He opens the envelope slowly, savouring the rarity. His eyes scan down the page, across the spindly words that fall over each other until they get to the end: Olivia. The girl from the train. He props his back against the wall, stretching out his legs across his bunk as he settles down to read.

The letter makes him smile. He loves the description of her journey from the station to Taigh Mor. He knows that road well. It is one of his favourite journeys, winding its way through the Highlands, passing only the occasional cottage, the tops of the hills almost touching the sky, the burns glimmering in the distance, the sudden smattering of hardy, ragged sheep or a lone red deer. It is a journey back in time.

He is delighted to discover that Nancy has lodged Olivia in the little bothy down by the loch. He wonders whether she knows that her uncle did that bothy up as a wedding present for his then young wife before the last war, and how special it was to the pair of them. He has no doubt that the place will work its magic on her. There is something so charmingly naïve about her letter. She has been cosseted and kept from the real world. He can’t help feeling excited at the prospect of her learning to love Scotland as he does.

What he would give to be there now. To lie in the silence broken only by the murmur of water on shingle and the rustle of the trees, instead of the hollow clanking of his ship and the thoughts and voices of so many men. Ironically it is only a few miles around the coast, but it might as well be a thousand miles away.

Charlie resists the urge to hold the letter to his nose, to breathe her in. Can it really be only ten days since they met? And now she has replied. Things couldn’t be better. He rests his head back against the cabin wall. Life is good. His first goal was to fly, and now that he’s doing it, the rest of his dreams will follow. Suddenly his future is something that is tangible, ready to be plucked in all its shining glory as soon as the war is over.

Night is drawing in and the light is fading. The aircraft carrier’s signal lamp winks its message to ask whether they can join the men on the battleship for a few drinks. Charlie is bursting with energy. He feels as though he could do anything. He joins Paddy and Frank, Mole and some of the other officers who want a closer look at the veteran ship. They motor across the black water of the harbour. The movement of a small boat is completely different to that of the aircraft carrier; the smell of salt water and the sloshing of the waves more powerful. The sea glints where the small light on their launch catches the ripples.

Although the old battleship – like all ships – is in blackout, Charlie can just make her out in the twilight: the pom-pom guns next to the funnel, and the huge fourteen-inch guns at the front trumpeting up to the sky, the lifeboats dangling on their davits like hanging baskets. The sound of the water changes as it slaps ineffectually at her sides.

‘Boat ahoy!’ Someone shines a light down on them. They blink up at it, unable to see anyone behind the brightness. An officer is there to greet them. He grabs Charlie’s hand firmly, gripping his forearm with the other hand. ‘Welcome aboard,’ he says.

It does them good to see new faces. The officers relax into a catch-up, trading stories of German reconnaissance and squeezing each other for news of home and where they might be sent next. Charlie wonders whether his father ever sat in this same wardroom, among the chink of glasses and the hum of men.

‘Any on-shore entertainment here?’ asks Frank.

‘Not unless you like sheep,’ says one of the officers, a man with a long, narrow nose.

All the men laugh, but Charlie says, ‘I love it up here. Think I might buy a place one day.’

Mole grunts. ‘Not on a sub-lieutenant’s pay, you won’t,’ he says.

‘I won’t be a sub-lieutenant for ever,’ says Charlie.

‘No,’ says Mole. ‘Knowing you, you won’t.’

‘Don’t tell me,’ says one of the older officers, with a wry smile, ‘you’ve got it all mapped out: captain, commodore, admiral?’

Charlie looks down at his drink. The liquid sloshes against the glass. ‘Doesn’t everyone want to progress?’ he says quietly.

‘Life never turns out how you expect,’ says the man with the narrow nose.

‘I do know that,’ says Charlie, thinking of his dead parents, feeling a lump in his throat and desperately trying not to let it escape into his mouth.

The older man is leaning forwards: ‘I had it all mapped out too. Pipe. Slippers … And look at me now. Back on a bloody ship, faced with another war.’

‘Isn’t it your duty—’ Charlie starts to say.

‘Duty? Duty! Don’t talk to me about bloody duty. I did my duty last time around …’

‘Leave him alone, Bruce. He’s only a youngster.’

Charlie is sweating. It is partly the whisky, partly embarrassment, partly anger. He grips the tumbler in frustration. He’s not that young. He’s twenty, the same age as his father was at the start of the last war, and he’s already doing things that boys can only dream of.

Bruce downs his drink, sighing as he tops up the glass again. ‘No offence, old boy,’ he says, rubbing his hand across his eyes and settling back in his chair. ‘I’m just a weather-beaten old fool, and you’re right. I’m glad we’ve got a bunch of optimists to see us through …’

To Charlie’s relief, the conversation is brought to an end there, as a rating knocks at the door to ask if the officers need anything further. Charlie recognises the freckle-faced boy immediately as one of the batch he escorted up here on the train. He gets to his feet and crosses the wardroom. ‘Summers, isn’t it?’ he says.

The boy nods, his cheeks colouring. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘How’s it all going?’

‘Very good, sir.’

‘They treating you well?’

‘Of course.’ Summers shifts nervously from foot to foot.

‘Is it all you thought it would be?’

‘And more, sir.’

‘I gather your training class is coming over to our ship tomorrow, to get a taste of life on an aircraft carrier?’

‘I believe so, sir.’

‘Well, I’ll look out for you, then. Send my regards to the other cadets who travelled with us, won’t you?’

‘I will, sir. Thank you, sir.’ Summers nods, still red-cheeked as he disappears away down the corridor.

Charlie feels as though he has reasserted some authority. He turns back to the men in the room, dusting down his jacket. ‘Probably time for us to get back,’ he says. ‘It’s been a long few weeks.’

Back on board his own ship, Charlie stands on the flight deck for a moment before heading down to his cabin. The harbour is so quiet that he can hear the capital ship’s boatswain’s mate piping down. The piercing notes echo across the water like a strange bird’s cry. Above him, the sky starts to shimmer. There is a line of sparkling luminescence in the sky, a ribbon of undulating neon pulsing over the ships. At the edge it is aquamarine and blue, and the stars still twinkle in the darker velvet sky around it. The Northern Lights. Instead of coal-black, the sea is beginning to glimmer luminous green. It is a moment of wonder, like receiving a letter. Charlie wonders if Olivia is watching them too: they are connected by this inky water that bleeds into the nooks and crannies of the northern shores of Britain.

Mole puts an arm around Charlie’s shoulder. ‘Don’t take it to heart, boyo. It’s been a hell of a week.’

‘What’s wrong with aiming high?’

‘Nothing at all. But you should remember there is more to life than just this. I know you’ve had it drummed into you by that fancy school you went to.’

‘Don’t they teach you the same at grammar school?’

‘Yes. But I also know you need more than that for a happy life.’

‘You mean, a wife and family? Like you.’

‘Exactly. Man cannot live by bread alone … there’s drink and women and singing …’ Mole starts to sing. It’s a song that Charlie recognises as ‘Calon Lân’, one of the Welshman’s favourites. The notes bounce across the harbour and out towards the hills. As his voice fades, so too do the lights in the sky, and once again they are left in silence and darkness. Charlie feels a deep hollow in the pit of his stomach and with surprise he realises his eyes have filled with tears. Must be the whisky. He leaves Mole on deck and heads for the isolation of his cabin.

Charlie is woken by a loud bang. It is 0104 in the morning. The night is black as coal. He stumbles to the door of his cabin. A signalman trots along the corridor. ‘It’s the battleship, sir,’ he says. ‘Some fuel or ammunition gone up in the bows.’

Charlie nods. Through his porthole he can hear a faint tinny voice. Probably a message on the ship’s Tannoy system. ‘OK. Thanks, Walker. Let me know if they need help.’

‘Will do, sir.’ Walker jogs back along the corridor, his feet reverberating through the metal tunnel.

Charlie turns back to his cabin and closes the door. He isn’t concerned. After all, this is a naval base. They couldn’t be safer. He has almost reached his bunk when there is another almighty boom. There is no mistaking that noise. It is an explosion – and a large one. He opens the porthole and sees flames across the water. He grabs his clothes, his boots, and runs up on deck still clambering into them. He pushes past the crowd of men to the rails. The battleship is listing like a drunk. Everyone is shouting at the same time: ‘Away lifeboat’s crew! What else can we do? Hurry!’ Charlie runs for the tender they used only a few hours ago. But it has already cast off with Frank and a petty officer to go and help. The aircraft carrier has switched on her searchlight and aims it at the water where the vast ship is now floundering, almost flat on her side.