По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

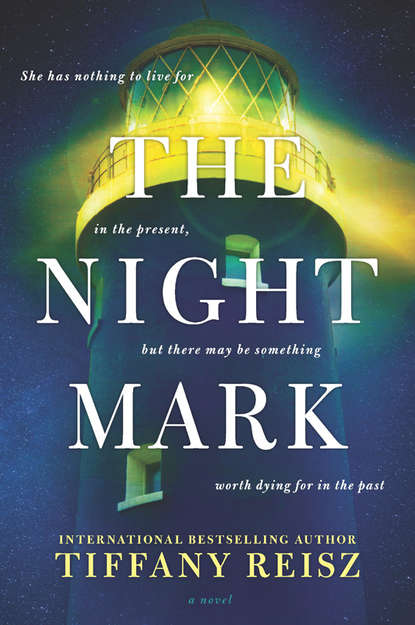

The Night Mark

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I don’t want to die here,” Faye said.

It wasn’t the dying that bothered her in that statement. It was the here. She didn’t want to die here in this cold, cold house with this cold, cold husband she slept with in a bed made of cold, cold iron.

“And I will die here if I stay,” she said with cold iron finality.

The look on his face said he believed her even if he wasn’t willing to admit it. She waited. He didn’t say anything more.

She paused at the bedroom door. She’d stay at a hotel tonight, then fly to her aunt’s house in Portsmouth tomorrow. She’d file for divorce there and let Hagen have everything. There would be nothing for the lawyers to fight over as long as she didn’t ask for anything. She’d be divorced by June 5, her thirtieth birthday. Ah, June—a great month for weddings, a better month for divorces. Widowed and divorced, two miscarriages and two failed IUI treatments, all before she turned thirty.

Give the lady a prize.

“You won’t contest the divorce?” Faye asked.

“No,” Hagen said.

Faye nodded.

“For what it’s worth,” Faye said, “I wish...”

Her throat tightened to the point of pain.

“What, Faye? What?”

“I wish I’d never married you. For your sake. Not mine.”

She looked at him, and he looked at her. She wondered if they’d ever see each other again. And she waited for her tears to come but they were gone, the valley dry again.

“Yeah, well,” he said, “you’re not the only one.”

And that was it. He didn’t weep. He didn’t scream. He didn’t argue. He didn’t beg. And when she picked up her suitcase and left Hagen alone in the bedroom, he didn’t follow her. It was over.

She put the suitcase in the trunk of her Prius—a gift from Hagen that he would probably demand she give back—and hit the button to open the garage. Before she backed out, she pulled her phone from her jeans pocket.

She reread Richard’s email. Sounded like a big project, this fund-raiser calendar thing. Landscapes, houses, ladies in dresses... She hadn’t worked a big job like that since getting married. She hadn’t done much of anything since getting married. But she’d need the money. And she’d need the distraction.

Faye hit Reply and typed her answer.

Richard—I just left husband.

In other words, I’ll take the job.

2 (#u5dfc0014-26a7-5683-8c38-2537ef8d0be1)

Faye made the divorce easy on Hagen and he stayed true to his word and made it easy on her. Faye asked for nothing but the Prius and the twelve thousand dollars she’d had in her bank account on their wedding day. He handed over the car keys and wrote her a check. And that was that. He got the house, the other car, the boat, the money and the all-important bragging rights. She’d left town, which gave him the freedom to conjure up any story he wanted. He could tell the world she’d cheated on him with every man alive if he so desired to play the cuckold. He could say she’d refused marriage counseling if he wanted to play the martyr. Or he could tell them the truth—that he wanted babies and her body clearly wasn’t on board with this program. She’d lost Will’s baby. She’d lost Hagen’s. And the two insemination attempts had failed.

Three strikes was an out, but four balls was a walk.

Faye walked.

It was easier to do than she’d thought it would be. Hagen hadn’t put up a real fight. Knowing him, he’d probably been secretly relieved. The past four years she’d slowly lost touch with the world until everything had started to take on the feel of a TV show, a soap opera that played in the background. Occasionally, she’d watch, but never got too invested. Finally, she’d simply switched off the television. The Faye and Hagen Show was over. No big loss. The show only had two viewers and neither of them liked the stars.

A couple months on the coast would do her good. The saltwater cure, right? Wasn’t that what the writer Isak Dinesen had said? “The cure for anything is salt water—sweat, tears, or the sea.” Faye should get more than enough of all three photographing the Sea Islands in the middle of summer.

As soon as she’d packed her bags and drove away from Hagen’s house for the final time, Faye hit the road. In summer tourist-season traffic, the drive from Columbia to Beaufort took nearly four hours. Who were all these people lined up in car after car heading to the coast? What did they want? What did they think they’d find there? Faye wanted to work, that was all. She wanted to do well with this assignment since one good job led to another and then another. Life stretched out before her from now until her death, her work like the centerline of the highway and if she kept her eye on that line maybe, just maybe, she might not careen off the edge of the road.

Faye took the exit to Beaufort, the heart of what was known as Lowcountry in South Carolina. It felt like its own country as the terrain turned flatter and greener and swampier the deeper she drove into. After the exit, she passed a huge hand-painted sign off to her right. Lowcountry Is God’s Country, it read in big black letters. Interesting. If she were God she’d pick the Isle of Skye in Scotland maybe. Kenya. Venice. But Lowcountry? Seemed an odd choice. She wondered what being “God’s country” entailed, and then she passed four different churches, four different denominations, and all in a quarter-mile stretch. Clearly God owned a whole lot of real estate around here.

Faye made it to Beaufort by dinnertime. Needing to conserve her money, Faye had rented a room in Beaufort. Just one room in someone else’s home. She wouldn’t have a private bathroom, a situation Hagen would have found an unacceptable affront to his dignity, but Faye found she didn’t mind, not at all. Now that she didn’t have to think of anyone’s needs but her own, she’d discovered just how little she needed.

The house was on Church Street, a faded Southern Gothic Revival river cottage, a revival someone had forgotten to revive. White paint in need of power washing, three tiers of verandas missing a baluster or five, Spanish moss and ivy competing for ownership of the trees... Faye liked it immediately. It was owned by Miss Lizzie, a woman who rented the rooms out mostly to college kids attending the University of South Carolina’s Beaufort campus. So few students attended classes in the summer, however, that Faye had ended up with what Miss Lizzie said was the best room in the house.

Faye’s hopes were not high, but Miss Lizzie, an older black woman with a spray of pure white hair around her head like an icon’s nimbus, welcomed her into the house with a wide smile that seemed genuine. Faye did her best to match it. The third-floor room she’d been given surpassed Faye’s low expectations by a large margin.

“Here you go,” Miss Lizzie said. “I keep this as my guest room. No kids up here. I’d hate to put a grown woman like you in the same hall as my college boys. They get a little rowdy. You’ll like it up here if you don’t mind the stairs. My sister stays here when she visits but she’s not coming round again until October. Too hot for her.”

“It’s beautiful,” Faye said, wearing a smile she didn’t have to fake. She hadn’t been impressed by anything in a long time, but this room spoke to her in its spareness. The floors were hardwood, a deep cherry stain polished to a high shine so that in the evening sunlight she could see every last rut and groove on the floor, elegant as an artist’s brushstrokes. The wounds gave it character and beauty. The bed was a four-poster, narrow, like something she’d seen in preserved historic homes. It bore an ivory canopy on top and ivory bed curtains; an ivory bedspread with a double-wedding-ring Amish quilt in a shade of dark and light blue was folded at the bottom. In case she got cold, Miss Lizzie said. South Carolina in June and July? Faye was fairly certain she wouldn’t have to worry about catching a chill.

“Closet over there,” Miss Lizzie said, pointing at a buttercream-yellow door. “Dresser there. These doors lead to the balcony,” she said, indicating a set of French doors. “No screen doors, so try not to let the mosquitoes in.”

“Are you Catholic?” Faye asked.

“Of course not. I go to Grace Chapel. It’s AME.” The tone of denial Miss Lizzie employed made it sound as if Faye had asked her if she were a government spy hiding out on foreign soil. Then again, that was what many people once thought of Catholics in the United States.

“I saw the prie-dieu.” Faye pointed at the carved wooden kneeler by the bed. A ceramic gray tabby cat sat on top of it next to a lamp. “That’s why I ask.”

“The what? I thought that was some kind of step stool or side table.”

“It’s for praying. Private prayer. You kneel on this bottom step here and maybe rest your prayer book on the top part.”

“You’re of the Catholic faith?” Miss Lizzie asked, touching her chest as if to clutch at nonexistent pearls.

“No, but I’m a photographer. I did a photo shoot of Catholic churches for a book once.”

“I see. You here to photograph things?”

“For a calendar. A fund-raiser.”

“Well, that’s nice, then. Who doesn’t need funds these days?”

Faye laughed. “Anyway, it’s very pretty.” Faye touched the prie-dieu. It was simply carved but sturdy stained rosewood. The wood was lighter where the knee would go on the bottom board as if someone had prayed on it many times. Were his prayers answered? Why did Faye assume it was a he?

“It’s from the lighthouse, the old one,” Miss Lizzie said.

“Lighthouse? The one on Hunting Island?”

She shook her head. “Not that one. North of Hunting Island, there’s another island. Bride Island.”

“Bride Island? That wasn’t in my guidebook.”