По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

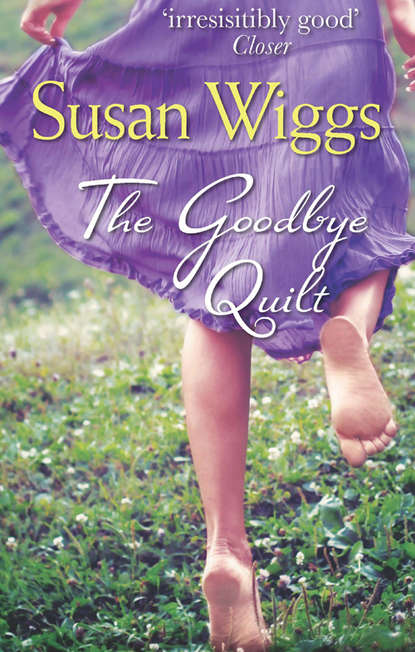

The Goodbye Quilt

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Oh, come on,” I chide her. “Is that what you really think?”

“I don’t know. I figure he’s been looking forward to this day for a long time. Dad’s good with change.”

Meaning I’m not. And although he might be good with this particular change, there’s a part of him that has come unmoored. Dan loves Molly with both a consuming flame and a heart-pounding fear. Their complicated relationship has always been full of contradictions. Dan was in the delivery room when Molly was born on a cold February morning eighteen years ago, and the moment the baby appeared in all her pulsing, slippery, newborn glory, he wept, the tears soaking into the paper surgical mask they’d made him wear. The first time Molly was placed in his arms, he held the tiny bundle with the shocked immobility of abject terror. He hadn’t smiled down into the red, wrinkled face, not the way I did, instantly a mother, with a mother’s serene confidence and a sense of accomplishment so intense I was floating. He hadn’t cooed and swayed to that universal internal lullaby all mothers begin to hear the moment the baby is laid in their arms. He had simply stood and looked as though someone had handed him a vial of nitroglycerin.

Yet last night, I awakened to find him crying. He was absolutely silent, but the bed quivered with his fight to keep from making a sound. I said nothing, but lay perfectly still, helplessly drifting. Have I lost the ability to comfort him? Maybe I just didn’t want to intrude. We are each dealing with the departure of our only child in our own way. When you’re married, you don’t get to be let in, not to everything.

“Trust me,” I assure Molly. “He’s going to miss you like crazy.”

“He never said so.”

“He wouldn’t. But that doesn’t mean he won’t be missing you every single second.”

“I guess.”

Too often, there’s a disconnect between Dan and Molly, despite the undeniable fact that they love each other. I pause, frowning at a knot that has formed in my thread. “That’s just the way he is,” I tell Molly. This is my role—the go-between, translating for the two of them.

I tease the knot loose and go back to my stitching. The border abuts a trapezoid-shaped swatch of neutral-colored lawn, snipped from the dress she wore to the eighth-grade banquet, the first grown-up dance of her life. At age thirteen she was impossible, taking drama to new heights and sullenness to new depths. I used to try to turn our dirgelike family dinners into something a little more upbeat. “What’s the highlight of your day?” I used to ask my husband and daughter. “What’s the one thing that makes it worth getting up in the morning?”

Dan had been grinding pepper on his salad in that deliberate way of his. Barely looking up, he said, “When Molly smiles at me.”

He startled both Molly and me with that remark. And our sullen, teenage daughter had smiled at him.

Now Molly’s phone rings with a familiar tone—an Eddie Vedder song called “The Face of Love.” It’s Travis’s ringtone.

A heartbreaking softness suffuses her face as she picks up. “Hi,” she says, her voice as intimate as a lover’s. “I’m driving.” She listens for a moment, then ends with a “Yeah, me, too,” and closes the phone.

More silence. The needle darts. The day slides by the car windows. Prairie towns between endless grasslands. We make a pit stop, eat some junk food, talk about nothing. Same as we always do.

DAY TWO

Odometer Reading 121,633

… it may have been some unconsciously

craved compensation for the drab

monotony of their days that caused the

women … to evolve quilt patterns

so intricate. Only a soul in desperate

need of nervous outlet could have

conceived and executed, for instance,

the “Full Blown Tulip” …

—Ruth E. Finley,

Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them

Chapter Three

“Remember this one?” I ask, angling part of the quilt into Molly’s line of vision.

“I guess.”

“I bet you don’t remember it.”

“Then why did you ask? You always do that, Mom.”

“Do I? I never noticed.”

“You’re always quizzing me about stuff you think should be important to me.”

“Really? Yikes.” I brush my hand over the piece of purple cotton, covered by lace.

“So what about that one?” She is instantly suspicious. All summer long, little “do-you-remembers” and “last times” have sneaked in—the last time we drove to the lake at the county line to set off fireworks, the last time Dan and I attended one of her piano recitals, the last time she went for a haircut at the Twirl & Curl.

“It’s from a dress your father bought you,” I say, needle pushing in and out, running a line of stitches to spell out Daddy’s girl.

“Dad bought me a dress? No way.”

“He did, at the Mexican Marketplace. I can’t believe you forgot.”

“Mom. What was I, three or four years old?”

“Four, I think.”

“I rest my case.”

In my mind’s eye, I can still see her turning in front of the hall mirror, showing off the absurd confection of purple cotton and cheap lace. “It swirls,” Molly had shouted, spinning madly. “It swirls!” I was less charmed when she insisted on wearing it to church for the next nine weeks. The dress fell apart years ago, but there was enough fabric left to work into the quilt.

Memories flow past in a swift smear of color, like the warehouses and billboards lining the interstate. When I shut my eyes, I can picture so many moments, frozen in time. So many details, sharp as a captured image—the wisp of my newborn baby’s hair, the sweet curve of her cheek as she nurses. I can still imagine the drape of her christening gown, which is wrapped in tissue now, stored in the bottom of the painted cedar chest in the guestroom. I can clearly see myself poking a spoonful of white cereal into a round little birdlike mouth. I see Molly spring forward on chubby legs off the side of the pool, into my outstretched arms.

All those firsts. The first day of kindergarten: Molly wore her hair in two tight pigtails, her plaid jumper ironed in crisp pleats, her backpack filled with waxy-smelling new crayons, sharpened pencils, lined paper, a lunch I’d spent forty-five minutes preparing.

“Do you remember your first day of school?” I ask her now, flourishing the part of the quilt made of the uniform blouse.

“Sure. My teacher was Miss Robinson, and I carried a Mulan lunch box.” Molly changes lanes and eases past a poky hybrid car. “You put a note in my lunch. I always liked it when you did that.”

I don’t recall the teacher or the lunch box, but I definitely remember the note, the first of many I would tuck into Molly’s lunch over the years. I always tried to write a few words on a paper napkin with a little smiling cartoon mommy, with squiggles to represent my hair, and the message “I LOVE.png U. Love, Mommy.”

I tried to upgrade my wardrobe for the occasion, wearing slacks, Weejuns and coral lip gloss from a department store counter. I felt important, compelled by mission and duty, as Molly chattered gleefully in the back of my station wagon.

Stopping at the tree-shaded curb of the school, I pretended to be calm and cheerful as I kissed Molly’s cheek, stroked her head and then smilingly waved goodbye. She met up with her friends Amber and Rani. The girls went inside together, giggling and skipping the whole way, into the redbrick institution that suddenly looked huge and forbidding to me.