По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

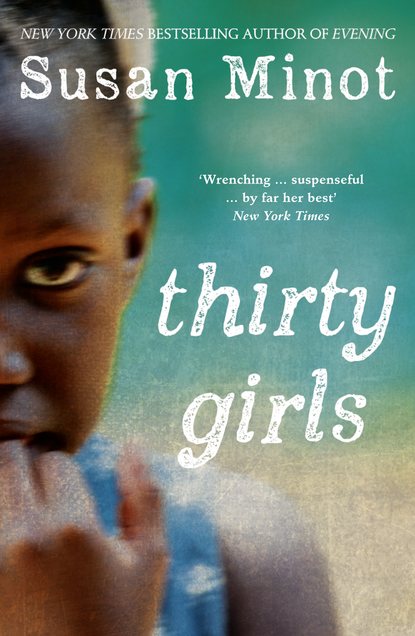

Thirty Girls

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They wouldn’t burn the chapel.

Sister, they murder children, these people.

They heard the tinkling of glass and the banging stopped. Instead of being a relief the sound of only shouting—of orders being given—and the occasional sputtering of fire was more ominous.

I still do not hear the girls, said Sister Chiara. She said it in a hopeful way.

They waited for something to change. It seemed they waited a long time.

The shouts had dropped to a low calling back and forth, and finally the nuns heard the voices moving closer. The voices were crossing the quadrangle toward the front gates. They were nearby. The nuns’ faces were turned toward George where he stood motionless against the whitewashed wall. Sister Giulia held the crucifix on her necklace, muttering prayers.

The noise of the rebels passed. The sound grew dim. Sister Giulia stood.

Wait, Sister Alba said. We must be sure they are gone.

I can wait no longer. Sister Giulia took small steps on the shaded pathway and reached George.

Are they gone?

It is appearing so, George said. You remain here while I see it.

No, George. She followed him onto the porch’s platform. They are my girls.

He looked at her to show he did not agree, but he would not argue with the sister. Behind her he saw the pale figures of the other nuns moving across the garden like a fog. You walk behind me, he said.

George unbolted the doors of the breezeway and opened them to the gravel driveway lit by the floodlights. They looked upon a devastation.

The ground was littered with trash—burned sticks and bits of rubber and broken glass. Scattered across the grass of the quadrangle in the shadows were blankets and clothes. George and Sister Giulia stepped down, emerging like figures from a spaceship onto a new planet. In front of the chapel, the Jeep was burning with a halo of smoke. Dark smoke was also bellowing up in long tubes out of the smashed windows of the chapel. But she and George turned toward the dormitory. They could see a black gap in the side where the barred window had been. The whole frame had been ripped out and used as a ladder. That’s how they’d gotten inside.

Bits of glass glittered on the grass. There were soda cans, plastic rope, torn plastic bags. The second dormitory farther down was still dark and still. Thank the Lord, that appeared untouched. Those were the younger ones.

The girls …, Sister Giulia said. She had her hands out in front of her as if testing the silence. She saw no movement anywhere.

We must look, George said.

They stood at the gaping hole where the yanked window frame was leaning. The concrete around the frame was hacked away in chunks. One light shone from the back of the dormitory, the other bulbs had been smashed.

From the bushes they heard a soft voice: Sister.

Sister Giulia turned and bent down. Two girls were crouched in the darkness, hugging their nightshirts.

You are here, Sister Giulia said, dizzy with gratitude. She embraced the girls, feeling their thin arms, their small backs. The smaller one—it was Penelope—stayed clutching her.

You are safe, Sister Giulia said.

No, Penelope said, pressing her head against her stomach. We are not.

The other girl, Olivia Oki, rocked back and forth, holding her arm in pain.

Sister Giulia gathered them both up and steered them out of the bushes into some light. Penelope kept a tight hold on her waist. Her face was streaked with grime and her eyes glassed over.

Sister, they took all of us, Penelope said.

They took all of you?

She nodded, crying.

Sister Giulia looked at George, and his face understood. All the girls were gone. The other sisters caught up to them.

Sister Chiara embraced Penelope, lifting her. There, there, she said. Sister Fiamma was inspecting Olivia Oki’s arm and now Olivia was crying too.

They tied us together and led us away, Penelope said. She was sobbing close to Sister Chiara’s face. They came to know afterward that Penelope had been raped as she tried to run across the grass and was caught near the swing. She was ten years old.

Sister Giulia’s lips were pursed into a tighter line than usual.

George, she said, make sure the fire is out. Sister Rosario, you find out how many girls are gone. I am going to change. There is no time to lose.

No more moving tentatively, no more discovering the damage and assessing what remained. She strode past Sister Alba, who was carrying a bucket of water toward the chapel.

Sister Giulia re-entered the nuns’ quarters and took the stairs to her room. No lights were on, but it was no longer pitch black. She removed her nightdress and put on her T-shirt, then the light-gray dress with a collar. She tied on her sneakers, thin-soled ones that had been sent from Italy.

She hurried back down the stairs and across the entryway, ignoring the sounds of calamity around her and the smell of fire and oil and smoke. She went directly to her office and removed the lace doily from the safe under the table, turned the dial right, then left, and opened the thick weighty door. She groped around for the shoebox and pulled out a rolled wad of bills. She took one of the narrow paper bags they used for coffee beans and put the cash in it then put the bag in the small backpack she removed from the hook on the door. About to leave, she noticed she’d forgotten her wimple and looked around the room, like a bird looking for an insect, alert and thoughtful. She went to her desk drawer, remembering the blue scarf there. She covered her hair with the scarf, tying it at her neck, hooking it over her ears. That would have to do.

When she came out again she met with Thomas Bosco, the math teacher. Bosco, as everyone called him, was a bachelor who lived at the school and spent Christmas with the sisters and was part of the family. He stayed in a small hut off the chapel on his own. He may not have been so young, but he was dependable and they would call upon him to help jump-start the Jeep, replace a lightbulb or deliver a goat.

Bosco, she said. It has happened.

Yes, he said. I have seen it.

Sister Rosario came bustling forward with an affronted air. They have looted the chapel, she said. As usual she was making it clear she took bad news harder than anyone else.

Bosco looked at Sister Giulia’s knapsack. You are ready?

Yes. She nodded as if this had all been discussed. Let us go get our girls.

Bosco nodded. If it must be, let us go die for our girls.

And off they set.

By the time they had left the gate, crossed the open field on the dirt driveway and were walking a path leading into the bush, the sky had started to brighten. The silhouette of the trees emerged black against the luminous screen. The birds had not yet started up, but they would any minute. Bosco led the way, reminding the sister to beware of mines. The ground was still dark and now and then they came across the glint of a crushed soda can or a candy wrapper suspended in the grass. A pale shape lay off to the side, stopping Sister Giulia’s heart for a moment. Bosco bent down and picked up a small white sweater.

We are going the right way, she said. She folded the sweater and put it in her backpack, and they continued on. They did not speak of what had happened or what would happen, thinking only of finding the girls.

They came to an area of a few straw-roofed huts and asked a woman bent in the doorway, Have they passed this way? She pointed down the path. No one had telephones yet information traveled swiftly in the bush. Still, it was dangerous for anyone to report on the rebels’ location. When rebels discovered you as an informant, they would cut off your lips. A path led them to a marshy area with dry reeds sticking up like masts sunk in the still water. They waded in and immediately the water rose to their chests. Sister Giulia thought of the smaller girls and how they could have made it. Not all the children could swim.

Birds began to sing, their chirps sounding particularly sweet and clear on this terrible morning. They walked on the trampled path after wringing out their wet clothes. Sister Giulia had been in this country now for five years and still the countryside felt new and beautiful to her. Mostly it was a tangle of low brush, tight and gray in the dry season, flushing out green and leafy during the rains. An acacia tree made a scrollwork ceiling above them and on the ground small yellow flowers swam like fish among the shadows.

They met a farmer who let them know without saying anything that they were going in the right direction, and farther along they caught up with a woman carrying bound branches on her head, who stopped and indicated with serious eyes that, yes, this was the right way. People did not dare speak and it was understood.

Другие электронные книги автора Susan Minot

Rapture

0

0