По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

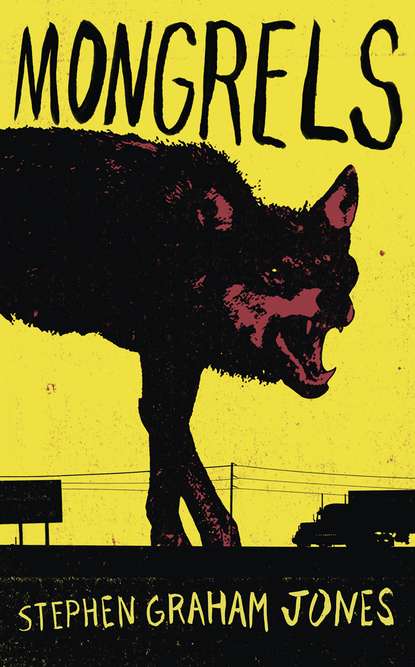

Mongrels

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Stephen Graham Jones

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#u5989fd7d-eb87-5c08-a6c3-b905105a4715)

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (#u5989fd7d-eb87-5c08-a6c3-b905105a4715)

My grandfather used to tell me he was a werewolf.

He’d rope my aunt Libby and uncle Darren in, try to get them to nod about him twenty years ago, halfway up a windmill, slashing at the rain with his claws. Him dropping down to all fours to race the train on the downhill out of Booneville, and beating it. Him running ahead of a countryside full of Arkansas villagers, a live chicken flapping between his jaws, his eyes wet with the thrill of it all. The moon was always full in his stories, and right behind him like a spotlight.

I could tell it made Libby kind of sick.

Darren, his rangy mouth would thin out in a kind of grin he didn’t really want to give, especially when Grandpa would lurch across the living room, acting out how he used to deal with sheep when he got them bunched up against a fence. Sheep are the weakness of all werewolves, he’d say, and then he’d play both parts, growling like a wolf, his shoulders pulled up high, and turning around to bleat in wide-eyed fear, like a sheep.

Libby would usually leave before Grandpa tore into the flock, the sheep screaming, his mouth open wide and hungry as any wolf, his yellow teeth dull in the firelight.

Darren would just shake his head, work another strawberry wine cooler up from beside his chair.

Me, I was right at the edge of being eight years old, my mom dead since the day I was born, no dad anybody would talk about. Libby had been my mom’s twin, once upon a time. She told me not to call her “Mom,” but I did, in secret. Her job that fall was sewing fifty-pound bags of seed shut. After work the skin around her eyes would be clean from the goggles she wore but crusted white with sweat. Darren said she looked like a backward raccoon. She’d lift her top lip over her teeth at him in reply, and he’d keep to his side of the kitchen table.

Darren was the male version of my mom and Libby—they’d been triplets, a real litter, according to Grandpa. Darren had just found his way back to Arkansas that year. He was twenty-two, had been gone six magical years. Like Grandpa said happened with all guys in our family, Darren had gone lone wolf at sixteen, had the scars and blurry tattoos to prove it. He wore them like the badges they were. They meant he was a survivor.

I was more interested in the other part.

“Why sixteen?” I asked him, after Grandpa had nodded off in his chair by the hearth.

Because I knew sixteen was two of eight, and I was almost to eight, that meant I was nearly halfway to leaving. But I didn’t want to have to leave like Darren had. Thinking about it left a hollow feeling in my stomach. All I’d ever known was Grandpa’s house.

Darren tipped his bottle back about my question, looked over to the kitchen to see if Libby was listening, and said, “Right around sixteen, your teeth get too sharp for the teat, little man. Simple as that.”

He was talking about how I clung to Libby’s leg whenever things got loud. I had to, though. Because of Red. The reason Darren had come in off the road—driving truck mostly—was Libby’s true-love ex-husband, Red. Grandpa was too old by then to stand between her and Red, but Darren, he was just the right age, had just the right smile.

The long white scar under his neck, he told me, leaning back to trace his middle finger down its smoothness, that was Red. And the one under his ribs on the left, that cut through his mermaid girlfriend? That had been Red too.

“Some people just aren’t fit for human company,” Darren said, letting his shirt go, reaching down to two-finger another bottle up by the neck.

“And some people just don’t want it,” Grandpa growled from his chair, a sharp smile of his own coming up one side of his mouth.

Darren hissed, hadn’t known the old man was awake.

He twisted the cap off his wine cooler, snapped it perfectly across the living room, out the slit in the screen door that was always birthing flies and wasps.

“So we’re talking scars?” Grandpa said, leaning up from his rocking chair, his good eye glittering.

“I don’t want to go around and around the house with you, old man,” Darren said. “Not today.”

This was what Darren always said anytime Grandpa got wound up, started remembering out loud. But he would go around and around the house with Grandpa. Every time, he would.

Me too.

“This is when you’re a werewolf,” I said for Grandpa.

“Got your listening ears on there, little pup?” he said back, reaching down to pick me up by the nape, rub the side of my face against the white stubble on his jaw. I slithered and laughed.

“Werewolves never need razors,” Grandpa said, setting me down. “Tell him why, son.”

“Your story,” Darren said back.

“It’s because,” Grandpa said, rubbing at his jaw, “it’s because when you change back to like we are now, it’s always like you just shaved. Even if you had a full-on mountain-man beard the day before.” He made a show of taking in Darren’s smooth jawline then, got me to look too. “Babyface. That’s what you always call a werewolf who was out getting in six different kinds of trouble the night before. That’s how you know what they’ve been doing. That’s how you pick those ones out of a room.”

Darren just stared at Grandpa about this.

Grandpa smiled like his point had been made, and I couldn’t help it, had to ask: “But—but you’re a werewolf, right?”

He rasped his fingers on his stubble, said, “Good ear, good ear. Get to be my age, though, wolfing out would be a death sentence now, wouldn’t it?”

“Your age,” Darren said.

It made Grandpa cut his eyes back to him again. But Darren was the first to look away.

“You want to talk about scars,” Grandpa said down to me then, and peeled the left sleeve of his shirt up higher and higher, rolling it until it was strangling his skinny arm. “See it?” he said, turning his arm over.

I stood, leaned over to look.

“Touch it,” he said.

I did. It was a smooth, pale little divot of skin as big around as the tip of my finger.

“You got shot?” I said, with my whole body.

Darren tried to hide his laugh but shook his head no, rolled his hand for Grandpa to go on.

“Your uncle’s too hardheaded to remember,” Grandpa said, to me. “Your aunt, though, she knows.”

And my mom, I said inside, like always. Whatever went for Libby when she’d been a girl, it went for my mom.

It was how I kept her alive.

“It’s not a bullet hole,” Grandpa said, working the sleeve of his shirt down. “A bullet in the front leg’s like a bee sting to a real werewolf. This, this was worse.”

“Worse?” I said.

“Lyme disease?” Darren said.