По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

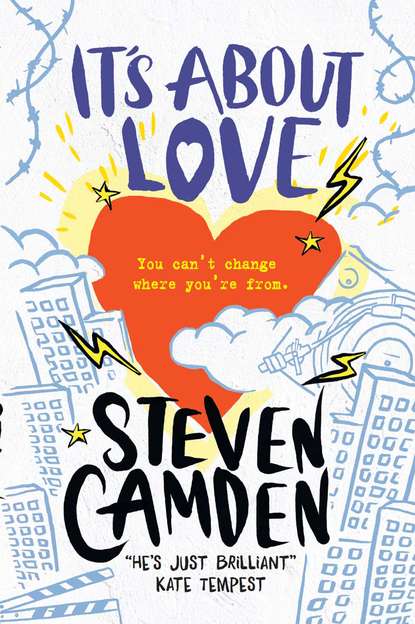

It’s About Love

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“But I don’t want honey and nuts.”

I laugh. Zia’s putting on a voice for his dad, playing both parts in this little comedy routine, hunching over and everything, pretending to adjust his glasses. Me and Tommy are his audience, sitting on the lime-green leather sofa. I can see our dark reflection in the black screen of the massive TV behind him.

“Are you kidding, Dad? Let’s treat ourselves, yeah?”

“I don’t want a treat, I want breakfast.”

“But Dad, you’re the West Midlands Carpet King, you can afford to splash out on a better cereal. Look, these ones are called clusters, they look good.”

“Cornflakes.”

“How about Cocopops?”

“Cornflakes.”

“Fine, but let’s at least get the Crunchy Nut, yeah?”

“You think I became successful by eating crunchy nuts? What’s wrong with you? You used to love cornflakes, you too good for cornflakes now?”

I laugh and Zia stops his routine.

I nod at him. “This is good stuff, man.”

Zia bows. “My life is my scrapbook.”

He’s got no idea how cool that sounded, and I make a mental note to write it down later.

“Has your dad seen you do it yet?” says Tommy.

“Are you mad? In fact, we should go. He’ll be back soon.”

Me and Tommy stand up.

“You should show him, man. You’re getting good,” I say.

“Oh yeah. ‘Hey, Dad, Tommy and Luke reckon I should jack in the supermarket job you’re making me do and sack off your plans for me and the family business. Yeah yeah, they think I should try and become a stand-up comedian. They think I’ve got potential.’”

His face is pure sarcasm. Zia’s dad doesn’t even like us in the house, let alone giving his only son career advice. Tommy looks round the room. “Yo. Your sister about?”

Zia digs his arm. “Shut up, yeah? It’s not funny.”

“What? I’m just saying.”

“What are you just saying, Tom?”

Tommy blinks slowly. “I’m just saying, that I think Famida is a rare beauty and I’d like to make her my wife.”

I laugh. Zia stares at Tommy. Tommy carries on. “My older, foxy wife.” He closes his eyes and smiles like he’s just tasted the best ice cream in the world. Zia goes for him and they’re in a two-man rugby scrum. I watch their reflection in the TV.

Zia joined our school in Year Five, but he really came into his own when we moved up to secondary. He was the kid who always said the cool thing at just the right time. Some of the one-liners he rocked to teachers were incredible. Like the time when Mr Chopping was laying into us in chemistry and shouted, “Do you think I enjoy spending my time with immature young boys?” and without even blinking, Zia was like, “I don’t know sir, I’d have to browse your internet history.” Brilliant.

I punch them both and they stop wrestling. Tommy cracks his neck and takes out a cigarette. Zia cuts him a look. “Don’t even joke you idiot, come on, let’s go.”

“Where we going, anyway?” I say.

Tommy puts his cigarette back and shrugs. Zia puts his hands on our shoulders. “Doesn’t matter. We got wheels!”

INT. CAR – DAY

Close-up: A pine tree air-freshener swings from the rear-view mirror to the sounds of boys laughing.

We don’t have anywhere to go and Tommy’s happy just driving around, so that’s what we do. I get shotgun and Zia’s in the back behind me. There’s no stereo in the car, but it doesn’t matter cos just driving with no sound feels good. Like a music video on mute.

Then I have an idea.

We drive round to old Mr Malcom’s house and nick apples from the tree in his front garden, then park outside our old school. It’s only been a summer since we left, but it feels like forever. The black metal front gates are locked and it looks kinda small.

“Shithole,” says Tommy.

Zia nods. “Load up.”

Standing in a line in front of the gates, we cock our arms back and try to hit the technology block windows.

I’m the only one to reach, my apple exploding on the thick double-glazed glass. “Eat that, Mr Nelson.”

We stop by West Smethwick park and watch the second half of an under-twelves game. It’s Yellows vs Reds. Within minutes, Tommy’s shouting instructions to the Yellows’ defence.

Some of the parents stare.

The Yellows win 5:1.

At about four we stop at Neelam’s on the high road and get masala fish and ginger beers, then park up near the bus stop and eat in the car. Heat from our food steams up the windows.

“We could go anywhere,” says Zia through a mouthful of naan just as I was thinking the exact same thing; how we could just choose a direction and drive. All we’d need is petrol money. Tommy nods and I wonder what places they’re both imagining. London. Manchester. Paris.

“Wolverhampton,” says Tommy.

“What?”

He looks at me. “We could drive to Wolverhampton.”

I stare at him. “Wolverhampton? That’s where you wanna go?”

“Yeah, what’s wrong with that?” He takes a big bite of his naan. “Jamie says wolves girls are well up for it.”

Zia leans forward in between our seats. “I never went to Blackpool.”

Tommy scoffs. “What the hell’s in Blackpool?”