По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

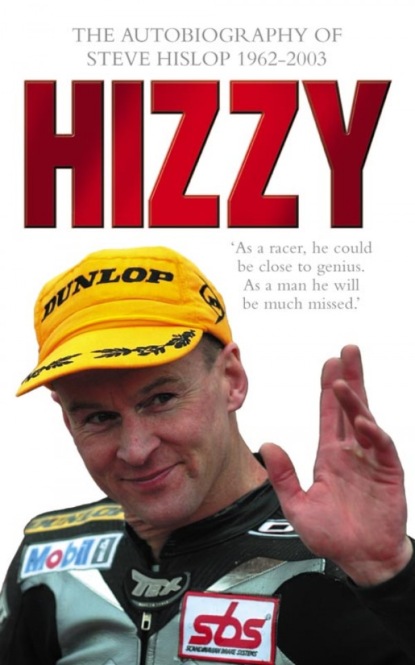

Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The doctors had checked all the x-rays and said the only thing that concerned them was a cloudy area around the C5 and C6 vertebrae in my neck. I told them I’d had a prolapsed disc in 1995 at that very spot which seemed to explain the cloudy area. I hate hospitals and when I looked around and saw an old woman who had choked on a sandwich and another old girl who hadn’t been able to shit for a month I thought, ‘I hate these places – I need to get out of here.’ So I signed myself out, even though the doctors wanted to keep me in overnight for observation, and I went back to the hotel that night. The following morning I drove my hire car to the airport and was back home on the Isle of Man a couple of hours after that.

When I saw a video of the crash on ITN news I realized how close to death or paralysis I had come. It looked much worse than triple world champion Wayne Rainey’s crash at Misano in 1993 did and he’s now wheelchair-bound for life because of that incident. Being paralysed or maimed scares me more than anything else in the world so I’d readily have chosen death over being stuck in a wheelchair. But then that’s a choice we never get to make – fate decides it for us.

But I wasn’t paralysed, I was just in pain all over. My head hit the inside of my helmet so hard that the mesh lining was imprinted on my forehead, and my forehead itself was so badly swollen that I looked like a Neanderthal. I had a black eye, my face was covered in cuts from where my helmet visor had come off allowing gravel to scratch my forehead and even my eyebrows were sore, although I can’t think how that happened. I felt as if I’d been put through a full cycle in a washing machine. However everything seemed to be in working order and I figured I’d be fully fit again in a few days, so that, as far as I was concerned, was the end of my Brands Hatch crash. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Just four days later I set off for a round of the British Superbike championship at Knockhill in Scotland. Everyone in the paddock was amazed to see me on my feet and most people, I think, were glad to see me alive. I managed to qualify for the races but felt really weak and couldn’t hold myself up on the bike properly. I figured I must have come back too early and since there were two weeks to recuperate before the next round at Cadwell Park, I decided to sit out the Knockhill meeting just to be on the safe side.

During those two weeks I had some physiotherapy and tried to lift some light weights but I still felt really weak down my left hand side. Then a really peculiar thing started to happen – I started walking into doors. I would put my left hand out to push open a door but my arm just buckled under the slightest strain so I’d end up slamming my face into the door. I wasn’t in any pain (apart from the fact that I kept banging my nose), but I just had no strength or feeling in my left arm. It was weird.

Anyway, I went to Cadwell as planned but in the first few laps of practice it was apparent that something wasn’t right. When you brake for a corner on a motorcycle you lift your body up out of the racing crouch to act as a windbreak which helps slow you down. This involves locking your arms against the handlebars as you lift up but every time I tried it I almost fell off the left-hand side of the bike. My left arm was just folding under pressure and it was way too dangerous to continue. I tried taking the strain on my knees against the fuel tank or with just my right arm on the bar but nothing seemed to work, so after six laps I pulled into the pits.

Everyone asked me what was wrong and I said I had no idea. I wasn’t in pain, I just couldn’t ride the bloody bike. Rob McElnea got really mad because he thought I was cracking up. I’ve been blamed a lot over the years for being fragile or temperamental when it comes to racing a bike because my results have not always been consistent and Rob probably thought that I just couldn’t be bothered to ride or that I’d lost my bottle for some reason.

You’ve got to realize that in motorcycle sport, it’s very common for riders to compete with freshly broken bones, torn ligaments or any other number of painful injuries. A trackside doctor is always on hand to administer painkilling injections to numb the pain for the duration of the race if required and riders often have special lightweight casts made to hold broken bones in place while they race. Basically, they will try anything just to go out and score some points so for me to explain that I was not in pain but just couldn’t ride the bike must have sounded a bit odd to say the least.

Anyway, there was no way I could race but I hung around Cadwell anyway and at one point bumped into a neurosurgeon I knew called Ian Sabin. He was a bike-racing fan and came to meetings when time permitted. I explained my problem so he carried out a few tests in the mobile clinic that attends all race meetings. He asked me to push against his hands as he held them out and I nearly pushed him over with my right hand but couldn’t apply any pressure at all with my left hand. After another couple of simple tests he told me I had nerve damage and needed to get an MRI scan as soon as possible.

I went to London for a scan and had to pay the £600 fee out of my own pocket but it was the best £600 I’ve ever spent as it probably saved my life (and I eventually claimed it back through my insurance anyway). Ian looked at the results and I could immediately tell he was worried. He didn’t tell me what he saw at that point but called another department and told them I needed an ECG test immediately. It was only then that he turned to me and said, ‘Steven, you have a broken neck. What’s more, you have been walking around and trying to race bikes for the last four weeks with a broken neck.’

Fuck! I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. How could I possibly have a broken neck and not notice? How did the hospital not diagnose it straight after the race? How do you fix a broken neck? Would I be able to ride again? All of these thoughts were rushing through my head as Ian explained that the C5 and C6 vertebra in my neck were broken and badly crushed as well. As a result of that my spinal column was twisted into an ‘S’ shape and to further complicate matters, a piece of sheared bone was chafing against the main nerve which controlled my left arm and was threatening to cut through it. No wonder I had no strength in it.

Ian said that I’d been incredibly lucky over the previous month because my head was, quite literally, hanging on by a bunch of fibres with no support from my spine. If I’d been slapped in the face or had knocked my head in any way, then that would have been the end of it – I’d have been dead, or even worse in my book, paralysed from the neck down. I thought back to all the daft things I’d done over the last month like going out on the piss when I could easily have fallen over. If I’d fallen off the bike at Knockhill or Cadwell, even if I’d slept on my neck in a funny position the results could have been catastrophic for me. The odds of not damaging the injury further in that month were incredible but somehow I’d beaten them. You could call it luck but I prefer to think of it as destiny: it simply wasn’t my time to die.

During the ECG test, they stuck needles in almost every muscle of my body and eventually found out that it was the nerve to my tricep muscle, in the rear of my left arm that had the most damage. It was deteriorating more with every passing day as the stray piece of bone gradually sawed its way through, and so I was scheduled for an operation as soon as possible.

Whilst I waited for the operation, I re-evaluated my entire life. I thought about everything I had done, pondered on everything I still wanted to do, and gradually realized how amazingly lucky I was to be getting a second chance at life when by all accounts, I should have been dead. I never once thought of quitting racing.

I’d never really believed there was a God and the crash didn’t change my mind. If there was a God, why would he have allowed my father to die in my arms when I was just 17? Why would he have allowed my kid brother to be killed racing a bike when he was only 19? Why, after my mother had lost her husband and son within three years of each other, would he then pair her off with an abusive second husband who battered her regularly? Why would he have allowed a good friend of mine to be beaten to death outside a chip shop because he refused to give his chicken and chips to a gang of thugs? No, I was pretty sure God didn’t exist or if He did, I didn’t like His way of doing things.

I also thought of how many of my friends and racing colleagues had been killed in racing accidents over the years while my own life had been spared so miraculously. The list makes for grim and depressive reading: names such as Joey Dunlop, Phil Mellor, Steve Henshaw, Ray Swann, Kenny Irons, Sam McClements, Simon Beck, Lee Pullan, Colin Gable, Gene McDonnell, Mark Farmer, Robert Holden, Klaus Klein, Donny Robinson, Neil Robinson, Steve Ward and Mick Lofthouse. I could go on but it’s not something I like to dwell on. We’re all going to die if we live long enough and I became more hardened to death than most people after losing my father and brother, so racing deaths never bothered me as much as they might have done.

But each and every one of those riders chose to dedicate his life to the sport of motorcycle racing because he loved it. It’s a sport that delivers thrills like no other but also one that punishes mistakes more harshly and more violently than any other. The risks are multiplied 10-fold when a rider also decides to race on closed public road tracks like the notorious Isle of Man TT. It is undoubtedly the most dangerous racing event in the world, but it’s also the event where I made my name and where I enjoyed so many great victories.

Since its inception in 1907, over 170 riders have been killed at the TT and the list is added to almost every year. Some years, as many as five riders are killed in the two-week event. Yet I won there 11 times at speeds which no one had ever witnessed before. Racing between walls and houses at over 190mph and averaging over 120mph for a lap was an awesome rush even if it was highly dangerous. But I cheated death on the world’s most unforgiving racetrack for 10 years and was never even hurt once while racing there. Ironically, it was a so-called ‘safe’, purpose-built short circuit that nearly claimed my life and almost left my mother with no sons at all.

I pondered on all these things as I awaited my operation and repeatedly questioned why I still wanted to race motorbikes more than anything else in my life. It certainly wasn’t for the financial rewards since I haven’t made any serious money from racing even though I’ve raced for more than 20 years. The truth is that when I retire I’ll have to get a normal job like everybody else because I have no savings worth talking about. Some racers, like my former team-mate, Carl Fogarty, have become millionaires from the sport but I’ve been financially naive throughout my career and consequently never got the rewards I feel I deserve.

Having said that, racing at least gives me some sort of wage to live on from day to day, so I suppose money was one of the reasons I had to get back on a bike again. After all, I have two small sons to support with no other obvious means of earning cash to feed and clothe them. But more than anything I wanted to get back on a bike again because I desperately wanted to win the British Superbike championship – the toughest domestic race series in the world.

Throughout my career people have always thought I could only win on dangerous street circuits and couldn’t adapt my style to the short sprint, purpose-built tracks, which require a different and more aggressive riding style. Even when I won the 250cc British championship in 1990 on short circuits people said I just got lucky, so the ‘road racer’ tag still weighed heavily round my neck.

In 1995 I won the British Superbike series but this time pundits said it was only because my arch-rival Jamie Whitham developed cancer midway through the season. It seemed as if nothing I did was enough to convince people that I was a world class short-circuit rider who could hold his own against the best in the world.

After winning that title in ’95 I had seven years of bad luck in the BSB series. Two of my teams folded mid-season through lack of funds, two other teams sacked me for ‘under performing’ and I didn’t complete three seasons because of injury. So, more than anything, I wanted to come back from my injuries this time and win the British title so convincingly that no one could ever have any more doubts about my ability on a motorcycle.

I don’t mind admitting that I was absolutely shitting myself going into that operation. Motorcycle racing may be dangerous but at least I was always the one in control: I could back off the throttle or slam on the brakes if things got too hot or I could even pull off the track and quit if I was totally unhappy about something. There was at least some sense of being in charge even if it was only a delusion. But being knocked out and having someone, however well qualified, operating on your spine? That’s really scary.

Lower spine operations are quite common and generally successful but the neck is a different matter. From the chest upwards, it’s like a bloody telephone exchange inside your body with all those nerves criss-crossing each other and that’s where things can go wrong. As I’ve said, my biggest fear is being paralysed so if the surgeons were going to mess up, I’d rather they just put me to sleep for good.

You’d think that for an operation on your neck, the surgeons would go in from the back, but in my case at least, they didn’t. Instead, they cut open my throat, pushed my windpipe aside and went to work from there. They picked out all the shattered pieces of bone and generally cleaned up the mess, then they cut open my hip and chipped a disc of bone from my pelvis to graft into my neck. I swear they must have used a bloody sledgehammer to chip that bone off because the pain in my pelvis when I woke up was like nothing on earth and I’ve had my share of serious injuries so I’m well accustomed to pain.

As you’d expect, I was also pretty groggy when I woke up and I remember wondering why the fuck there was a red Christmas tree bulb hanging out of my pelvis and one hanging out of my neck too. As I came a bit more to my senses I realized they were blood drains – little suction pumps that suck out any surplus blood so it doesn’t start congealing. My neck and throat felt OK but that bloody hip was unbelievable and when Ian wanted me on my feet the morning after the operation I was horrified. Man that hurt.

Anyway, normally that procedure would have been enough and any other patient would be told to take it easy for a while until the bone healed itself. But because my surgeon knew I wanted to go racing again as soon as possible, he strengthened my neck by screwing in a titanium plate which I still have in there – and always will have as a matter of fact.

A CT scan showed the operation had gone well and my neck was stable and I was on my way home two days later, but I’d been told there was no guarantee that I’d ever get any feeling or strength back in my left arm. Ian said it might return in six weeks, six months, one year or perhaps never at all. I had almost torn that nerve clean out of the spinal column as my body was twisted in the crash and no one could tell if my arm would ever be anything more than the relatively lifeless object that was dangling by my side. I was at nature’s mercy.

Every day for weeks – even though I don’t believe in God – I prayed for some feeling to come back, but every day for weeks it didn’t. I tried to build up strength in it but could only lift light weights and I was starting to get really depressed thinking my career was over and that I was going to be left with a useless arm. I couldn’t even try to set up a deal for the following season because I didn’t know if I’d be able to ride a bike or not.

Then one day, about two months after the crash, it started happening. I felt a slight sensation on the back of my hand and then in my index finger. It wasn’t much but it was definitely something. I thought, ‘Yes! Here we go, I’m back in business.’ I felt totally elated but not as elated as I was when, near Christmas time, I was finally able to lock my left arm out fully. That was the best Christmas present I’d had since my first son was born on Christmas Day in 1997. I was over the moon.

It was game on after that and I started training slowly and gently to rebuild some muscle in my wasted arm. That was day number one of life number two as far as I was concerned and I never stopped thinking about racing after that. There were still some months until the start of the new season so I had time to try and organize a ride for the year, even though I’d burned my bridges with most teams over the last few years. But I didn’t care – I’d been given a second chance at life and I wasn’t about to waste it. Somehow I would find a bike to race even if it meant remortgaging my house and buying one myself. The way I saw it, I had nothing to lose because I should have been dead anyway.

Steve Hislop was back – and he was going to win the British Superbike championship come hell or high water.

2 Shooting Crows (#ulink_8ee09618-0302-5b19-baf6-31ce0800de99)

‘My real name’s actually Robert Hislop but my dad made a mistake when he registered me.’

The Isle of Man TT is a totally unique event and probably attracts more controversy than any other sporting fixture on the calendar.

It’s held on the world famous ‘Mountain’ circuit that runs over 37.74 miles of everyday public roads on the Isle of Man. The roads are, naturally, closed for the races but they’re still lined with hazards such as houses, walls, lamp-posts, hedges and everything else you would expect to find on normal country roads.

Because of the dangers and the number of competitors who have been killed there, the event lost its world championship status in 1976 when top riders like Barry Sheene, Phil Read and Giacomo Agostini refused to race there any longer. When you consider that the current, fastest average lap speed is held by David Jefferies at 127.29mph and bikes have been speed-trapped at 194mph between brick walls, it’s easy to understand the dangers of the place, as there’s no run-off space when things go wrong. But the thrill of riding there is unique and that’s what keeps so many riders coming back year after year.

Riders don’t all start together at the TT – they set off singly at 10-second intervals in a bid to improve safety although mass starts have occurred in the past. That means the competitors are racing against the clock and the longest races last for six laps which equates to 226 miles and about two hours in the saddle at very high speeds and on very bumpy roads. It’s an endurance test as much as anything else and you can’t afford to lose concentration for a split second or you are quite literally taking your own life in your hands. It is an event like no other on earth.

The TT (which stands for Tourist Trophy) fortnight is traditionally held in the last week of May and the first week of June and the Manx Grand Prix is traditionally held on the same course in September. The latter event is purely amateur with no prize money and it exists as a way for riders to learn the daunting 37.74 mile course before tackling the TT proper. The name should not be confused with the world championship Moto Grand Prix series because the two have nothing in common.

Both the Manx Grand Prix and the TT races have played a huge part in my life, which is why I’m describing them in detail now. Without them I simply wouldn’t be where I am today, or even writing this book, and a basic understanding of the nature of both events is crucial to understanding my later career.

I first visited the Manx GP as a child, then later on spent 10 years racing on the Mountain course, both at the Manx and the TT. I grew to love the Isle of Man so much over the years that I moved there in 1991 and it’s where I still live to this day.

It was my father Alexander, or ‘Sandy’ as he was known, who got me interested in the TT and the Manx GP in the first place as he raced at the Manx back in the 1950s. I went on to have incredible success at the TT and that’s really where I made my name in the world of motorcycling. But believe it or not, the Steve Hislop who won 11 TT races (only two men in history have won more) isn’t actually called Steve at all thanks to one of the daftest blunders anyone’s dad ever made.

I may be known as Steve Hislop throughout the bike-racing world but on every piece of documentation that proves who I am, the name given is actually Robert. I still don’t know exactly how it happened but it was definitely my dad’s doing. Both he and my mum, Margaret, had decided on calling me Steven Robert Hislop and that’s the name I was christened under, but my dad messed up big time. For reasons known only to him, he registered me as Robert Steven Hislop and to this day even my passport carries that name.

Robert was my grandfather’s name, but he died when he was just 30 after he fell from the attic in his dad’s blacksmith’s workshop. His was the first in a series of tragic early deaths in my family.

I was born at 7.55pm on 11 January 1962 at the Haig Maternity Hospital in Hawick in the Scottish Borders. But although I was born in a Hawick hospital, I’m not actually from the town itself despite what all those race programmes, TV commentators and magazine articles have said over the years. I’m actually from the little village of Chesters in a parish called Southdean, a few miles south east of Hawick. My mum was only 16 when she had me, while my dad was a good bit older at 26 – a bit of a cradle snatcher was the old boy!

Money was tight so we all lived with my widowed granny for the first few months of my life. Mum worked in the knitwear mills; knitwear is a big trade in the Borders and my dad was a joiner who worked for a small country joinery firm in Chesters village before eventually buying the business when the owner died.

My younger brother, Garry Alexander Hislop, was born in the same hospital as me on 28 July 1963, just 17 months after I was and we were very close right from the start. I loved having a brother.

Dad loved his bikes and was very friendly with the late, great Bob McIntyre, another Scottish bike racer and the first man ever to lap the Isle of Man TT course at 100mph. Dad raced between 1956 and 1961 on a BSA Gold Star and a 350cc Manx Norton. He travelled to all the little Scottish courses that don’t exist any more, such as Charter Hall, Errol, Crimond and Beveridge Park, including some circuits in the north of England such as Silloth – a track which would later have tragic consequences for my family.

He was a pretty handy racer in the Scottish championships but never really had the money to do it properly. He used to ride to meetings on his bike with a racing exhaust strapped to his back, fit it to the bike for the race then change back to the standard one and ride home again! That was proper clubman’s racing. As I mentioned earlier, my dad also raced at the Manx Grand Prix a few times usually finishing midfield but when mum became pregnant with me he packed in the racing game to support the family.