По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

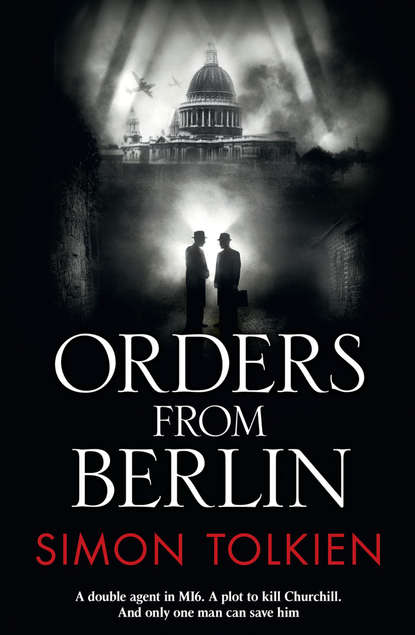

Orders from Berlin

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But Bertram’s intervention seemed to revitalize his wife in a way that nothing else could. She glanced over at him and then, as if making a conscious decision, began to drink the tea. Quaid made a mental note – there was no way these two lovebirds were happily married.

‘I come in the mornings to make my dad his lunch, and then, when I go, I leave him his supper – on a tray,’ said Ava, putting down the cup with a shaking hand. She spoke slowly, and there was a faint lilting cadence in her voice that Quaid couldn’t place at first, but then he realized that it was the remnants of an Irish accent. Which was where she must have got her bright green eyes from as well, he thought to himself. ‘And to begin with, I didn’t come back when the raids started because I thought he’d be sensible and go down in the basement with the neighbours. But then Mrs Graves – the woman you met, she was here a minute ago – she told me he was staying up here, refusing to come down. Like he’d got a death wish or something …’

‘There’s no need to exaggerate, my dear,’ Bertram said primly.

‘Please let the lady answer the questions,’ said Quaid, shooting him a venomous look.

‘He’s obstinate and pig-headed, always thinks he knows best,’ Ava went on. It was as if she were unaware of the interruption, and Quaid noticed her continued use of the present tense in relation to her father, as if some part of her were still in denial that he was dead. ‘I asked him to come and stay with us, but he wouldn’t hear of it. Oh no, he’s got to be here with his stupid books.’

Ava’s resentment was obvious as she gazed up at the overflowing shelves on all sides. It couldn’t have been easy being her father’s daughter, Quaid thought. Not that being married to Dr Bertram Brive looked much fun, either, for that matter.

‘So you started to come over here to see if he was all right?’ asked the inspector, prompting her to continue.

‘Yes.’

‘When?’

‘A few days ago.’

‘And did he go down to the shelter?’

‘Yes. But I knew that he wouldn’t have done without me being here.’

‘And your husband – has he been over here before in the evenings, like tonight?’

‘No.’

‘Even when there have been air raids?’

Ava shook her head.

‘I fail to see the relevance,’ said Bertram, whose face had turned an even brighter shade of red than before, although whether from anger or anxiety it was difficult to say. He was going to say more, but a cry from his wife silenced him.

‘All he had to do was go downstairs—’ She broke off again, covering her face with her hands as if in a vain effort to recall her words – ‘go downstairs’ – because instead her father had taken a quicker way down, falling through the air like one of Hitler’s bombs, landing with that unforgettable crunching thud at her feet. She shut her eyes, trying to block out the vision of his tangled broken body. But it did no good – it was imprinted on her mind’s eye forever by the shock.

‘I should never have let him go out without me,’ she said.

‘Out?’ repeated Quaid, surprised. It was the first he’d heard about the dead man having gone anywhere that day.

‘Yes, he insisted. It was after we came back from the park. I take him there after lunch most days. He likes to go and look at the ack-ack guns, “inspect the damage” he calls it, and poke his walking stick in people’s vegetable patches. They’ve got the whole west side divided up into allotments now,’ she added irrelevantly. ‘Digging for victory. I remember him making a joke about that, turning over some measly potato with his foot. Laughing in that way he has with his lip curling up, and now, now—’ She broke off again, looking absently over towards the fireplace, where a walnut-cased clock ticked away on the oak mantelpiece, impervious to the death of its owner two floors below.

The same glassy-eyed look had come over Ava’s eyes that had been there earlier, and this time Quaid glanced impatiently over at his assistant standing in the corner. Trave hadn’t said anything since they’d got upstairs, but now, as if accepting a cue, he went over and squatted beside the grieving woman.

‘Look, I know this is hard,’ he said, putting his hand over hers for a moment as he looked into her eyes, speaking slowly, quietly. ‘People dying – it’s not supposed to be this way, is it? Bombing makes no sense. But this is different. Somebody killed your father for a reason, pushed him over the balustrade out there. We can’t pretend it didn’t happen. You saw it. And maybe you can help us find out who did that to him. If you tell us everything you know. Can you do that, Ava? Can you?’

Ava looked down at the long-limbed young man in his ill-fitting suit and nodded. She was surprised by him, touched at the way he’d chosen instinctively to make himself lower than her, treating her as if she were in command of the situation. And he made her feel calm for some reason. Mrs Graves had told her that he was the one who’d caught her from falling when they were downstairs, and then there was the way his pale blue eyes looked into hers with a natural sympathy, as if he instinctively understood how she felt.

Not like Bertram. Behind Trave’s shoulder, Ava’s husband shifted his weight from one foot to the other, making no effort to conceal his mounting irritation.

‘I’m not happy with this, Inspector,’ he said, turning to Quaid. ‘Your boy’s badgering my wife. Can’t you see what she’s been through? In my professional opinion—’

‘I don’t need your professional opinion,’ said Quaid, cutting him off. ‘If I want it, I’ll ask for it. Carry on, Mrs Brive,’ he added, turning to Ava. ‘Tell us what happened today.’

‘He was fine this morning,’ she said, keeping her eyes on the younger policeman as she spoke even though she was answering the older one’s question. ‘I got here about half past one and made him his lunch just like I always do. He read The Times and did the crossword, and then, like I said, we went over to the park, and he was in a good mood – a really good mood for him. It was when we came back here that the trouble started.’

‘Trouble?’ repeated Quaid.

‘Yes, there was a note …’

‘What kind of note?’

‘Just a folded-over piece of paper. I didn’t get to read it. Someone had called while we were out and left it with Mrs Graves downstairs. She brought it to him up here, and he read it a couple of times. He seemed agitated, walking up and down, and then he went over to his desk and he was looking at papers, even a couple of books, acting like I wasn’t there, like he usually does. I went into the kitchen and I’d just started to wash up the lunch things when he called me, shouted, rather, telling me I had to phone him a taxi, that he needed one straight away—’

‘Why didn’t he call one himself?’ asked Quaid, interrupting.

‘Because he could ask me to do it,’ said Ava. Again Quaid picked up on the anger in the woman’s voice and thought, not for the first time, how strange it was the way the newly bereaved could feel so many contradictory emotions all at the same time. Part of Ava was obviously still struggling with her constant irritation at the unreasonable demands of her living father, while another part of her was trying to absorb the reality of his death; trying to come to terms with the impossible experience of seeing him smashed to pieces on the floor at her feet.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: