По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

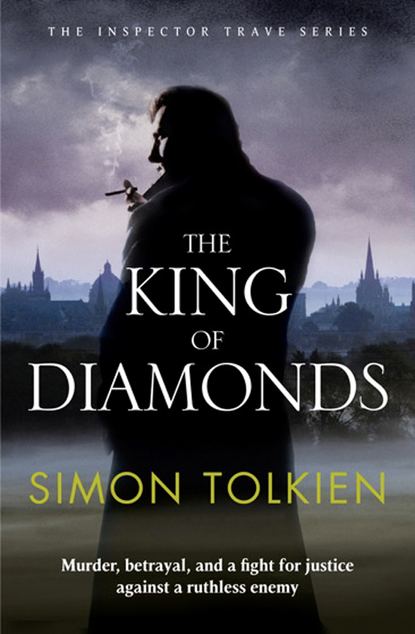

The King of Diamonds

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The red Triumph. The one over there,’ said the man, pointing to his right. ‘It’s got a full tank.’

‘Thanks. Come on, Davy,’ said Eddie, opening his door and beckoning David to follow. ‘We need to get a move on.’

Shutting the door, David looked back through the car window, anxious to get at least one look at this stranger who had done so much to help him escape, but it was as if the man had read his mind. In the minute since he’d parked, he’d turned the collar of his coat up around his ears and pulled his hat down over his forehead so that all David got to see was a flash of the man’s black beard before he was gone, driving back down to the road and picking up speed as he went around the corner and disappeared from sight. But the man’s voice stayed in David’s head. It had been high-pitched, effeminate sounding, not at all what he would have expected from one of Eddie’s friends.

‘Who was that?’ asked David, getting into the Triumph beside Eddie, who already had the engine on.

‘You don’t need to know,’ said Eddie in a voice that brooked no argument. ‘Do you still want to go to this Blackwater Hall place?’

‘Yes. That was the deal, remember. You promised me, Eddie,’ said David. There was an edge of panic to his voice, as if he was about to lose his self-control.

‘All right, all right, I remember. There’s no need to get all crazy about it. Just try and relax, okay?’

Eddie drove out of the city over Magdalen Bridge and headed out on the Cowley Road at a precise thirty miles per hour. David still kept looking over his shoulder, scanning the night for police cars.

‘Can’t you go any faster?’ he asked impatiently.

‘And get caught for speeding after all we’ve been through? No way. That’s a sucker’s game.’

David leaned forward, drumming his fingers on the dashboard.

‘Where’s the gun?’ he asked feverishly. ‘You promised me a gun.’

‘In there under your fucking fingers. And can’t you stop doing that? It’s driving me crazy.’

‘Sorry,’ said David, opening the glove compartment and taking out the nickel-plated revolver that was lying inside.

‘Christ, there’s a whole lot of money in here too,’ he said, holding up a see-through bag containing a large bundle of banknotes.

‘What the hell?’ said Eddie, sounding angry suddenly. ‘That’s not supposed to be in there.’

‘Where’s it supposed to be then?’

‘With our clothes in the back, away from the gun,’ said Eddie, keeping his eyes on the road as he jerked his thumb behind his head toward a small suitcase lying on the back seat. ‘The gun’s loaded, so be careful, okay?’

David nodded, barely listening. A strange calm had settled down on him since he’d taken hold of the small snub-nosed revolver that he now held cradled in the palm of his hand. Having it made him feel different inside. It meant the end of being told what to do; he could give the orders now. He thought of Claes’s scarred, waxy face, and his hand clenched involuntarily around the handle of the gun. The polished wood felt smooth and hard. It would be different this time.

They passed the Morris car factory on the left, its blue towers illuminated by the moonlight, and David remembered how the bottom of the Cowley Road used to be full of bicycles at five o’clock as the workers swarmed out of the factory on their way home. Like India, or how he imagined India anyway. But now the road was deserted and they were all alone in the night. Under a bridge and past a few straggling houses and they were out in the open countryside. David felt his heart hammering inside his chest: Katya was out there in the darkness only a mile or two away with no idea of what was coming her way.

‘Left, left,’ he shouted at the last moment as the turn to Blackwater came into view, but Eddie seemed to know already, and soon they were climbing the hill that David remembered so well. Past the church and out of the village until they came to the bend in the road and the fence beside the path that led up to Osman’s boathouse; the last place that he’d been as a free man.

‘All right, turn off here,’ said David. ‘You can park under the trees. If you keep your lights off no one’ll see you from the road.’

‘Unless they’re looking,’ said Eddie. ‘I’m waiting here half an hour, okay, like we agreed. Until five past one. Provided no one comes. If you’re longer than that, it’s your lookout because I’m out of here.’

‘Fair enough,’ said David. ‘But then I’ll need this too.’

Reaching into the glove compartment, he opened the bag with the money and helped himself to a wad of notes. Looking at Eddie defiantly, he stuffed them in his pocket.

‘Just in case,’ he said. ‘I won’t be long.’

But he never saw Eddie again as a free man.

David was grateful for the moonlight, but still there was little risk of his getting lost. He’d been down the path to the boathouse many times. Always the boathouse, never the house, he reflected bitterly, except on that one occasion when Katya had had the place to herself and even then she was as nervous as a cat. Because her uncle didn’t think he was good enough, didn’t like the fact that he didn’t go to the university and had a common name like Swain. Not like that bastard, Ethan. To the manor born he was, until he got that knife in his back. Just there. Standing outside the boathouse, David looked down to the water’s edge, to where Ethan’s body had lain, and then beyond to where the moon was shining silver ripples down onto the black surface of the lake. Everything was quiet. There was no wind in the trees, just the sound of the dark water gently lapping against the dock. It was an evil place, David thought. Beautiful but evil. Like Katya.

Gripping the gun in his hand, David turned away from the lake, heading into the woods. He picked his way carefully, but it wasn’t long before he came out into the open and paused, looking across the lawn toward the side of the house. There were no lights on in the windows that he could see, and there was no sound either. The mermaid fountain in the front courtyard must have been switched off for the night. This was the best place to cross the lawn, but still David hesitated, hating to risk himself out in the open, imagining unseen eyes watching from the shadows. But he had no choice. He knew that. He’d come too far to stop now. And so, steeling himself, he burst from the trees, running with his head down across the moonlit grass. He made it to the other side, but in his haste he’d forgotten about the rosebushes growing under the windows. They tore into his prison shirt and trousers and he had to bite his lip hard to stop crying out as he disentangled himself from the thorns.

He was outside the window of Osman’s study. He tried opening the sash without success – he could see it was fastened by a catch in the centre. But if he could just reach his hand through the pane above, he could open it. One blow would surely break the glass, and if everyone was asleep upstairs, and the door was shut, then maybe no one would hear. He had to take the chance. The first time he hit the pane with the butt end of the gun it only cracked, but the next time the glass shattered. David stood motionless in the darkness, waiting for lights, waiting for shouts, but nothing happened. Somewhere out in the trees an owl hooted, but otherwise the silence was as complete as before. Nothing stirred. Quickly he knocked the rest of the broken glass out of the pane and then, wrapping his hand in the sleeve of his torn shirt, he reached through the opening and turned the clasp, pulling the bottom half of the window gently up toward him.

Carefully, he climbed inside and then extended his arms in front of him, moving gingerly forward like a blind man. Katya had shown him the room when she gave him a tour of the house on that day when her uncle was away, and he thought he remembered a reading lamp on the corner of the desk. Seconds later he felt its shade and pressed down, searching for the switch. It clicked and suddenly the study was bathed in a pale green light. David blinked, getting his bearings. There was a big painting over the mantelpiece above the fireplace, some biblical scene it looked like. Probably valuable like everything else Osman owned, David thought bitterly, taking in the rich luxury all around him – the thick Axminster carpet, the rows of leather-bound books with golden titles on their spines, the silk curtains. David remembered his damp, dark, evil-smelling cell back in Oxford Prison and the contrast between the two rooms made him angry, made him want to smash something. But that wasn’t why he was here. He needed a torch, some light to guide him through the house. But there was nothing on the desk apart from the lamp and a telephone, and the drawers were just full of useless papers except for the top one in the centre that was locked. Stealthily, David ventured out into the corridor, leaving the door open behind him to give a little light, enough to see the shape of the long oval table in the room opposite. And on the table were candles, a whole line of them: tall white candles in high silver candlesticks. More suited to an altar than Osman’s dining table, David thought inconsequentially as he felt in his pocket for his matches.

Now, with the light, everything was easier. With a candle held aloft in one hand and the gun gripped in the other, he walked slowly down the corridor to the front hall, and stopped suddenly stock still at the foot of the wide ornamental staircase, gazing up into the luminous green eyes of a black cat sitting in the middle of the fourth stair up, barring his way. The animal seemed disembodied, indivisible from the surrounding darkness. For a moment they stared at each other without moving, but then David sensed the cat’s back beginning to arch as if it was about to spring, and instinctively raised the gun and candlestick in front of his face to ward off its attack, but instead it ran past him down the stairs. He felt its fur against his leg before it disappeared behind him into the shadows on the other side of the hall.

David felt his legs trembling underneath him and breathed deeply several times, exhaling his fear into the darkness before he steeled himself to the task ahead and began slowly to climb the stairs. Pictures and portraits lined the walls, but David looked neither to his right nor his left, concentrating all his attention instead on the ground beneath his feet, taking each step as if it might be his last. He knew where he was going. Katya had taken him to her room on that day when she had shown him the house. It was halfway down the top-floor corridor on the left. You had to lean down when you went inside because there was a slope in the ceiling. He remembered lying on her narrow bed; he remembered the taste of her kisses on his mouth. Her nervousness about him being there, about her uncle coming home and finding them, had made the afternoon more exciting than any of their previous encounters. His heart had pounded inside his chest like it was going to burst. Just like now.

Walking down the corridor almost on tiptoe, he thought he heard something – a rustling or a movement behind him. He turned, hesitating whether to go forward or back. Perhaps it was someone sleeping behind one of the closed and half-closed doors that he had passed. He had no idea who else slept up here. But now all was quiet again. Softly, he moved forward, coming to a halt outside Katya’s door.

Here comes a candle to light you to bed,

Here comes a chopper to chop off your head.

The words of the old nursery rhyme came unbidden into his head, and he smiled as he placed the candlestick carefully on the floor, put out his hand, and opened the door.

CHAPTER 7

Detective Inspector Trave woke with a start. He’d been deeply asleep, fighting the noise of the telephone ringing insistently beside his bed.

‘What is it?’ he asked blearily, still half-inhabiting the dream he’d been having: a bad dream that had been recurring lately in which shapeless shadows were coming toward him on a cliff’s edge and there was nowhere left to hide. His Dunkirk dream he called it, remembering 1940, when the world had gone up in flames. Who was to know if it wouldn’t happen again?

‘Sorry to wake you, sir,’ said a young, brisk voice on the other end of the line. ‘It’s a murder: young female shot in the head. At a place called Blackwater Hall. It’s outside Blackwater village on the London Road.’

‘Blackwater Hall,’ Trave repeated, coming fully awake.

‘Yes, that’s right. Do you want directions? I’ve got them here.’

‘No, I know Blackwater Hall. Get hold of Adam Clayton for me, will you? Tell him to meet me there.’

‘He’s already on his way, sir. He was on night duty when we got the call.’

‘Good. Thanks,’ said Trave, replacing the receiver.

Homicide at Blackwater Hall. It wasn’t the first time he’d heard those words. And people aren’t murdered in the same place twice for no reason, he thought as he got dressed, made himself a triple-strength cup of coffee, drank it in three gulps, and went out into the night.

Trave drove quickly through the empty streets and out into the dark countryside while his mind raced, remembering people and events that he’d been trying for a long time to forget. It was like the door of a lumber room had finally given way under the weight of what was stacked up behind it. Images from the past passed quickly in front of his mind’s eye like a succession of ghosts – Ethan Mendel lying dead, with the lake water lapping around his dark hair and his outstretched arms; David Swain’s hollow face collapsing in on itself as the jury foreman announced the guilty verdict; Titus Osman’s smug eyes twinkling behind his manicured beard as he entertained his guests at that dinner party after the trial, with Vanessa sitting on his left, listening to the bastard’s tall tales with such rapt attention.

Why had he taken Vanessa that night? Trave asked himself the same useless question for the thousandth time. Useless because he knew the answer. He hadn’t wanted to go. The Mendel case had left him feeling obscurely dissatisfied, a viewpoint evidently not shared by the jurors, who had taken less than two hours to convict. But Creswell, his boss, had insisted, and Trave had taken Vanessa with him to Blackwater Hall because he didn’t want to go on his own and because he felt guilty that she never went out; that he’d not been able to help her at all through those long, hard months and years after their son, Joe, died. Trave had had his job to fall back on, but she’d had nothing. Just him, and he’d been no support, worse than no support in fact. They’d grieved soundlessly and separately, trying to avoid each other in the passages and corridors of their empty house until their marriage withered away and died. Not with a shout; not even with a whimper. In a cold and weary silence.

He and Vanessa were finished long before the night that he took her to Osman’s to celebrate the end of another successful case. He realized that now. And yet she had looked so delicate, so fragile, that evening in a white dress that she hadn’t worn in years. He remembered her laughing in the bedroom before they left, saying that perhaps losing weight wasn’t such a bad thing after all, and he remembered how she’d bent her head to allow him to fasten the faux pearl necklace that he’d bought her as a present twenty years earlier, after Joe was born. His hands on her neck replaced by Osman’s hands – Osman, who could afford to pay more for a necklace than Trave earned in a year. Trave shuddered, braking hard to avoid the line of police cars with flashing lights parked in a line on the road up ahead. They must be searching the woods, he thought, as he turned through the open gate and drove up between the tall, moonlit trees to Osman’s house.