По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

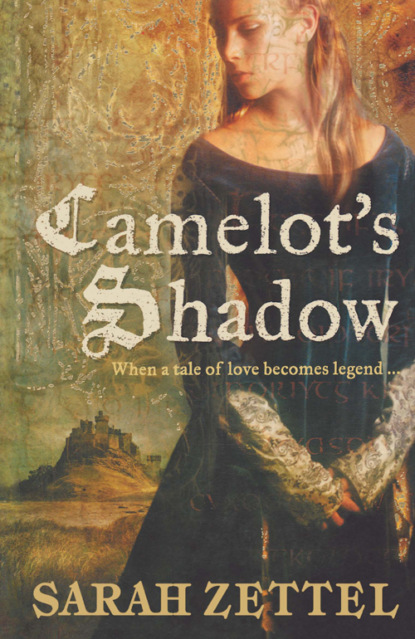

Camelot’s Shadow

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Daylight faded from the world with painful slowness. Rhian lingered over her sewing while the rush lights and the hour candle burned low around her. She sent Aeldra running for wine, for a posset, for a lavender-rinsed cloth for her brow, pretending that a headache kept her from seeking sleep.

At last, because she could think of nothing else, she sent Aeldra for a bed warmer. Alone, she tried to think. Rhian did not want to tell Aeldra any more than she already knew. When the household discovered Rhian gone, Aeldra would be the first one questioned, and Aeldra would not lie to her lord and lady. To do so was to risk being turned out of the hall to fend for herself in the hedgerows. Which left the question of how Rhian could send the maid away long enough to make her escape. She could not even allow herself be put to bed in her nightclothes, because she would have to dress alone and in the dark afterwards. It would take an age when every second would be precious.

Aeldra, however, solved her dilemma for her. She returned, not with the bed warmer, but with a brown cloak draped over her arms.

‘If my lady were to choose to wear this,’ Aeldra said quietly. ‘Anyone who saw her might think they were seeing one of the serving women instead.’

Stunned, Rhian accepted the cloak, a lump rising in her throat. ‘They will question you.’

Aeldra folded her hands in her familiar way. ‘And I will say my mistress said she went to meet young my Lord Vernus in the charcoal burner’s shed by the well of St Ethelrede.’

‘It will be a lie,’ Rhian whispered.

‘Not if you say it now.’

Slowly, Rhian repeated her maid’s words. ‘I’m sorry, Aeldra,’ she said, laying the brown cloak in her lap. ‘I knew you were my friend, but did not realize how true a friend.’

The maid’s smile was kind. ‘Young women seldom understand such things. Especially when the friend is apt to be exacting and sharp of tongue.’

Rhian glanced at the slash-marked candle beside her bed. It had been burning for three hours, and had been lit at twilight. ‘Is it safe now, think you?’

Aeldra leaned towards the door and put her hand to her ear in a practised gesture. ‘I hear no one.’

Rhian drew the cloak about her shoulders. A full handspan of her dress showed out underneath it, as she was some inches taller than Aeldra, but hopefully no one would be able to discern the colour or quality of the exposed fabric from one swift glance in the dark.

Aeldra fussed with the carved bone clasp and then, unexpectedly, kissed Rhian on the cheek. ‘God be with you, my lady.’

‘And with you, Aeldra.’

There was no time to linger. Rhian squeezed Aeldra’s hand, claimed her satchel, and opened her chamber door. The corridor outside was still and dark. She could not risk a light. She laid her hand on the cool stones of the left-hand wall and hurried ahead, trying to step only lightly on the rushes underfoot.

Behind her, Aeldra closed her door, cutting the golden candlelight off sharply, and leaving Rhian alone in the dark.

Rhian faltered only briefly. She called to mind what awaited her if she were caught, and that thought lent her speed. Her fingertips found the threshold leading to the staircase and her foot found the first stair. Feeling her way carefully, she began her descent.

Light flooded the world suddenly, making Rhian blink and miss her step. She stumbled, and looked back before she could stop herself, and found she looked up into her mother’s face.

Mother stood at the top of the stairs, frozen in the flickering light of a tallow candle. Only her eyes moved, as she took in the maid’s brown cloak, the satchel, and Rhian’s face peering out of the shallow hood. Rhian lifted her chin.

A single tear glistened on Jocosa’s cheek. Her mouth shaped words. Rhian thought she said, ‘God be with you.’ Then, her mother turned back the way she had come. Within two heartbeats, she vanished into the corridor’s shadows.

Rhian drew the hood down further over her face, more to hide her tears than her visage, and hurried out into the cool spring night.

Whitcomb had indeed not failed her. Rhian rounded the corner of the brewer’s shed to see him standing in its shelter, well out of the silver-grey light the curved quarter-moon sent forth. His gloved hand, however, held the reins for not one horse, but two. The first was Thetis, a grey mare, the horse Rhian had learned to ride on. She was no longer so fast or so spirited, but she was still strong and steady, and she knew Rhian well. The other was Blaze, a chestnut gelding with a white forehead and fetlocks that Whitcomb often rode as he surveyed the lands for her father.

Rhian stared accusingly at Whitcomb, now seeing that he wore his old leather hauberk and hood, and that he had his long knife at his waist and his bow and quiver of arrows slung over his shoulder. He said nothing, but even in the darkness she could read his face plainly enough.

I am coming. I will not let you do this alone. If you order me back, I will follow you.

‘Father will be angry with you when he finds out,’ she murmured.

‘I have braved my lord’s anger before,’ replied Whitcomb with a grim smile. ‘And never with greater cause.’

There was no time for argument. The moon was already well up, and if mother had been stirring, others might be about. In truth, Rhian had no heart to try to order him away. His solid presence would make what she must do less lonely.

Whitcomb held Thetis’s head while Rhian stowed her satchel in the saddlebag. Inside she found a number of small but useful items Whitcomb had thought to add – a hunting knife, a spare bowstring, a pair of riding gloves. She mounted the horse and Whitcomb passed up her bow and quiver and handed her the reins. Then, expertly, if a little stiffly, he swung himself up onto Blaze’s back. The horses were longtime stable mates and old friends with their riders, so they stepped up quickly in answer to the lightest of urgings. Despite this, their hoofbeats on the packed earth of the yard sounded to Rhian like thunder. She could not help but glance back towards the hall that had been her only home. No light shone in any of the windows, not even her mother’s.

Tears threatened again, and Rhian turned her face quickly towards the night beyond the yard.

They rode across the cleared fields where the damp air was heavy with the scent of freshly ploughed earth. They crossed the chattering beck, its clear water flowing like liquid moonlight over round stones. Both deeply familiar with the countryside, they had no difficulty in finding the track through the forest that would lead them down to the broad Roman road. The rustles of the night-waking animals accompanied them. An owl hooted once overhead. The stars in all their millions filled the sky with glory and the wind blew chill, but soft, across Rhian’s skin. Slowly, she felt the ache in her throat begin to ease.

Perhaps it would not be so bad. Perhaps the Mother Superior of St Anne’s would shelter her without requiring that she take vows. The emerald ring and the rest would, after all, buy a small convent much that it needed. Perhaps Whitcomb could find some excuse to travel alone again and visit her there, bringing Vernus with him. Perhaps a small deception could be given out that would ensure the priest who came to hear the sisters’ confessions would agree to marry Rhian to Vernus on the spot…then they could have their wedding night, and make sure the deception became the truth. Then no one would have to know what father had done, and she would not have to be the cause of his dishonour. For despite all, she found she still had love in her heart for him.

Perhaps mother could make father see reason after all, and Rhian would be able to go home and live in peace again without resorting to such elaborate games to keep her freedom.

Games. Played on a board of ivory and ebony. What is it every woman wants?

Rhian closed her mind tightly against these thoughts. It had been a dream, after all. A dream. She could not let it distract her now.

Ahead, the black trunks of the trees parted just enough to show the stretch of road the Romans had laid, still straight and flat even after all these years. But Rhian’s eyes, which had become well-accustomed to the dark, picked out something standing just at the point where the track met the road. It was not a tree, nor yet a road marker. It might have been a standing stone, but there had never been any such in this place.

Whitcomb urged Blaze into the lead. Past him, she saw the wind catch hold of cloth, and realized that what she saw was a tall man wrapped in a dark robe.

‘Who is that?’ Whitcomb demanded.

The figure spoke, and its voice was low and cold. ‘I am Euberacon Magus, and you, old man, have what is rightfully mine.’ Euberacon turned towards her and in the light of the waxing moon she saw his hooded eyes glinting like a serpent’s – cold, inhuman, and filled with the knowledge of death.

Rhian’s mouth went instantly dry. She pulled Thetis to a halt. She did not ask how this could be, she did not have thought enough in her head for that. She only knew deep and sudden fear at the sound of that voice and the dark sheen of those hooded eyes. This was the one to whom her father had promised her life, and he had come to collect.

Thetis whickered and stamped. Rhian pressed her knees into the grey mare’s ribs. Thetis balked, but began slowly to back. The track was narrow here, and there wasn’t enough room to turn her easily.

‘Stand aside for my lady,’ Whitcomb commanded. ‘Or do you relish the thought of being run down by a pair of horses?’

Now she could see that the dark-robed man had thin lips and that they twitched into a smile. Whitcomb dug his heels into Blaze’s sides and the horse started forward.

No! she tried to shout, but no sound came.

Euberacon raised his hand, and Blaze reared up high, screaming in sudden, unbearable terror. Utterly unprepared, Whitcomb crashed to the ground. Blaze fled into the darkness, running in blind panic past the sorcerer who stood still as a stone, caring not a bit as his robes rippled in the wind of the terrified animal’s passing.

‘I can make that creature run itself to death,’ said Euberacon calmly, as if remarking on the weather. ‘I can do the same to a man. Shall I prove these things to you, so you will see I may not be brooked or gainsaid?’

Whitcomb groaned and tried to rise. The sorcerer glanced down at him, distantly, as if the fallen man were no more than a stick of wood.

Anger overrode the fear that filled Rhian. ‘Leave him be!’ She flung herself from Thetis’s back. The sorcerer did not seem concerned for her shout or her sudden movement. Steel glinted in the moonlight as he drew a wickedly curved knife from his belt. The sight of it stopped Rhian’s heart. Whitcomb rolled, trying to get away, trying to rise, but although he pushed himself up on his arms, it was only to fall again. Rhian pulled her bow off her shoulders and an arrow from her quiver.

‘Do not touch him!’ she cried as she nocked the arrow in the string. ‘Can you make a beast run itself to death? I can hit a mark at fifty yards.’ She drew the string back next to her ear, sighting along the shaft. Even in the dark Euberacon Magnus would be an easy target.

‘Run,’ croaked Whitcomb, rolling to his side again, struggling still to rise. ‘Run!’