По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

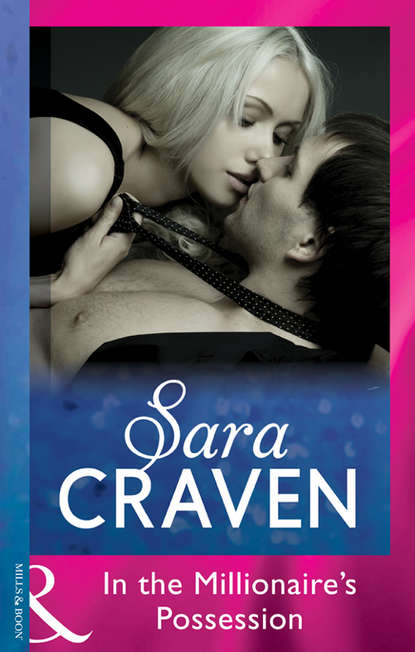

In The Millionaire's Possession

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She walked under the arched gateway and stood in the courtyard, looking at the bulk of the house in the starlight. Half-seen, like this, it seemed massive—impregnable—but she knew how deceptive it was.

And it wasn’t just her own future under threat. There were the Marlands, George and Daisy, who’d come to work for her grandfather when they were a young married couple, as gardener and cook respectively. As the other staff had left George had learned to turn his hand to more and more things about the estate, and his wife, small, cheerful and bustling, had become the housekeeper. Helen, working alongside them, depended on them totally, but knew unhappily that she could not guarantee their future—specially from Trevor Newson.

‘Too old,’ he’d said. ‘Too set in their ways. I’ll be putting in my own people.’

You’ll be putting in no one, she’d told herself silently.

I wish I still felt as brave now, she thought, swallowing. But, even so, I’m not giving up the fight.

Monteagle opened to the public on Saturdays in the summer. Marion Lowell the Vicar’s wife, who was a keen historian, led guided tours round the medieval ruins and those parts of the adjoining Jacobean house not being used as living accommodation by Helen and the Marlands.

Her grandfather had been forced to sell the books from his library in the eighties, and Helen now used the room as her sitting room. It had a wonderful view across the lawns to the lake, so the fact that it was furnished with bits and pieces from the attics, and a sofa picked up for a song at a house clearance sale a few miles away, was no real hardship.

If the weather was fine Helen and Daisy Marland served afternoon teas, with home-made scones and cakes, in the courtyard. With the promise of warm sunshine to come, they’d spent most of Friday evening baking.

Helen had been notified that a coach tour, travelling under the faintly depressing title ‘Forgotten Corners of History’ would be arriving mid-afternoon, so she’d got George to set up wooden trestles, covered with the best of the linen sheets, and flank them with benches.

Placing a small pot of wild flowers in the centre of each table, she felt reasonably satisfied, even if it was a lot of effort for very moderate returns. However, it was largely a goodwill gesture, and on that level it worked well. Entries in the visitors’ book in the Great Hall praised the teas lavishly, particularly Daisy’s featherlight scones, served with cream and home-made jam.

For once, the coach arrived punctually, and as one tour ended the next began. Business in the courtyard was brisk, but evenly spaced for a change, so they were never ‘rushed to death’, as Mrs Marland approvingly put it. The weather had lived up to the forecast, and although Monteagle closed officially at six, it was well after that when the last visitors reluctantly departed, prising themselves away from the warmth of the early-evening sun.

The clearing away done, Helen hung up the voluminous white apron she wore on these occasions, today over neatly pressed jeans and a blue muslin shirt, kicked off her sandals, and strolled across the lawns down to the edge of the lake. The coolness of the grass felt delicious under her aching soles, and the rippling water had its usual soothing effect.

If only every open day could go as smoothly, she thought dreamily.

Although that would not please Nigel, who had always made his disapproval clear. ‘Working as a glorified waitress,’ he’d said. ‘What on earth do you think your grandfather would say?’

‘He wouldn’t say anything,’ Helen had returned, slightly nettled by his attitude. ‘He’d simply roll up his sleeves and help with the dishes.’

Besides, she thought, the real problem was Nigel’s mother Celia, a woman who gave snobbishness a bad name. She liked the idea of Helen having inherited Monteagle, but thought it should have come with a full staff of retainers and a convenient treasure chest in the dungeon to pay the running costs, so she had little sympathy with Helen’s struggles.

She sighed, moving her shoulders with sudden uneasiness inside the cling of the shirt. Her skin felt warm and clammy, and she was sorely tempted to walk round to the landing stage beside the old boathouse, as she often did, strip off her top clothes and dive in for a cooling swim.

That was what the thought of Nigel’s mother did to her, she told herself. Or was it?

Because she realised with bewilderment that she had the strangest sensation that someone somewhere was watching her, and that was what she found suddenly disturbing.

She swung round defensively, her brows snapping together, and realised with odd relief that it was only Mrs Lowell, coming towards her across the grass, wreathed in smiles.

‘What a splendid afternoon,’ she said, triumphantly rattling the cash box she was carrying. ‘No badly behaved children for once, and we’ve completely sold out of booklets. Any chance of the wonderful Lottie printing off some more for us?’

‘I mentioned we were getting low the other evening, and they’ll be ready for next week.’ Helen assured her, then paused. ‘We have had a good crowd here today.’ She gave a faint grin. ‘The coach party seemed the usual motley crew, but docile enough.’

Mrs Lowell wrinkled her brow. ‘Actually, they seemed genuinely interested. Not a hint of having woken up and found themselves on the wrong bus. They asked all sorts of questions—at least one of them did—and he gave me a generous tip at the end, which I’ve added to funds.’

‘You shouldn’t do that,’ Helen reproved. ‘Your tour commentaries are brilliant, and I only wish I could pay you. If someone else enjoys listening to you that much, then you should keep the money for yourself.’

‘I love doing it,’ Mrs Lowell told her. ‘And it gets me out of the house while Jeff is writing his sermon,’ she added conspiratorially. ‘Apparently even a pin dropping can interrupt the creative flow. It’s just as well Em’s got a holiday job, because when she’s around the house is in turmoil. And it’s a good job, too, that she wasn’t here to spot the coach party star,’ she went on thoughtfully. ‘You must have noticed him yourself during tea, Helen. Very dishy, in an unconventional way, and totally unmissable. What Em would describe as “sex on legs”—but not, I hope, in front of her father. He’s still getting over the navel-piercing episode.’

Helen stared at her, puzzled. ‘I didn’t notice anyone within a hundred miles who’d answer to “dishy”—especially with the coach party. They all seemed well struck in years to me.’ She grinned. ‘Maybe he stayed away from tea because he felt eating scones and cream might damage his to-die-for image. Perhaps I should order in some champagne and caviar instead.’

‘Maybe you should.’ Mrs Lowell sighed. ‘But what a shame you missed him. And he had this marvellous accent, too—French, I think.’

Helen nearly dropped the cash box she’d just been handed. She said sharply, ‘French? Are you sure?’

‘Pretty much.’ The Vicar’s wife nodded. ‘Is something wrong, dear?’

‘No—oh, no,’ Helen denied hurriedly. ‘It’s just that we don’t get many foreign tourists, apart from the odd American. It seems—strange, that’s all.’

But that wasn’t all, and she knew it. In fact it probably wasn’t the half of it, she thought as they walked back to the house.

She always enjoyed this time after the house had closed, when they gathered in the kitchen to count the takings over a fresh pot of tea and the leftover cakes. And today she should have been jubilant. Instead she found herself remembering that sudden conviction that unseen eyes had been upon her by the lake, and it made her feel restive and uneasy—as well as seriously relieved that she hadn’t yielded to her impulse by stripping off and diving in.

Of course there were plenty of French tourists in England, and their visitor might well turn out to be a complete stranger, but Helen felt that her encounter with Marc Delaroche in the Martinique had used up her coincidence quota for the foreseeable future.

It was him, she thought. It had to be …

As soon as Mrs Lowell had gone Helen dashed round to the Great Hall and looked in the visitors’ book, displayed on an impressive refectory table in the middle of the chamber.

She didn’t have to search too hard. The signature ‘Marc Delaroche’ was the day’s last entry, slashed arrogantly across the foot of the page.

She straightened, breathing hard as if she’d been running. He might have arrived unannounced, but his visit was clearly no secret. He wanted her to know about it.

She simply wished she’d known earlier. But there was no need to get paranoid about it, she reminded herself. He’d been here, seen Monteagle on a better than normal working day, and now he’d gone—without subjecting her to any kind of confrontation. So maybe he’d finally accepted that she wanted no personal connection between them, and from now on any encounters they might have would be conducted on strictly formal business lines.

And the fact they’d been so busy today, and their visitors had clearly enjoyed themselves, might even stand her in good stead when the time came for decisions to be made.

At any rate, that was how she intended to see the whole incident, she decided with a determined nod, then closed the book and went back to her own part of the house, locking up behind her.

Helen awoke early the next morning, aware that she hadn’t slept as well as she should have done. She sometimes wished she could simply turn over and go back to sleep, letting worries and responsibilities slide into oblivion. But that simply wasn’t possible. There was always too much to do.

Anyway, as soon as the faint mist cleared it was going to be another glorious day, she thought, pushing aside the bedcover and swinging her feet to the floor. And, as such days didn’t come around that often, she didn’t really want to miss a moment of it.

She decided she’d spend the day in the garden, helping George to keep the ever-encroaching weeds at bay. But first she’d cycle down to the village and get a paper. After all, they might finish the crossword, earn some money that way.

George was waiting for her as she rode back up the drive. ‘All right, slave driver,’ she called to him. ‘Can’t I even have a cup of coffee before you get after me?’

‘I’ll put your bike away, Miss Helen.’ George came forward as she dismounted. ‘Daisy came down just now to say you’ve a visitor waiting. Best not to keep him, she thought.’

Helen was suddenly conscious of an odd throbbing, and realised it was the thud of her own pulses. She ran the tip of her tongue round her dry mouth.

‘Did Daisy say—who it was?’ she asked huskily.

He shook his head. ‘Just that it was someone for you, miss.’

She knew, of course, who it would be. Who it had to be, she thought, her lips tightening in dismay.

Her immediate impulse was to send George with a message that she hadn’t returned yet and he didn’t know when to expect her. But that wouldn’t do. For one thing it would simply alarm Daisy and send her into search-party mode. For another it would tell her visitor that she was scared to face him, and give him an advantage she was reluctant to concede.