По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

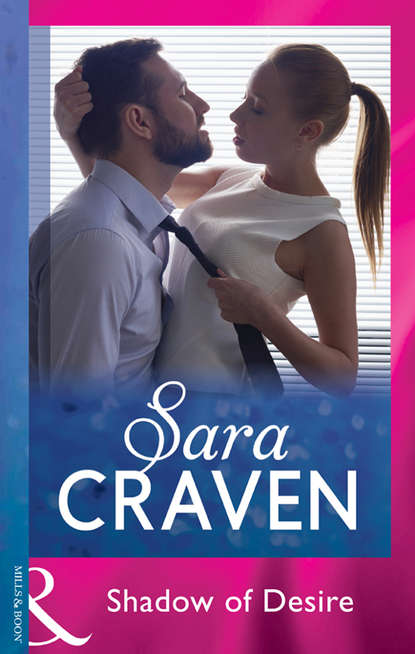

Shadow Of Desire

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There was a long silence, then Ginny said with some difficulty, ‘Mr Hendrick, I know I’ve given you a rather poor first impression of my abilities, but …’

‘There are no buts,’ he cut across her incisively. ‘Even if you carried out your instructions to the letter, I still wouldn’t have been prepared to keep you on.’

‘But that’s very unfair,’ she protested.

‘It’s an unfair world. Didn’t you know?’ he returned shortly. ‘You’re young, inexperienced and volatile—and that’s a mixture I need like a hole in the head. But don’t worry, I’ll simply tell Mrs Lanyon I’ve been forced to make other arrangements. I won’t tell her about the shambles here tonight. You’ll get your reference.’

She stood staring at him, all the colour drained from her face. Only an hour before, life had been happy and settled. She’d been on top of the world, but now after a few careless words from this man, she was facing disaster again. And if it was only herself, she thought numbly. How was she going to tell Tim and Aunt Mary of this sudden reversal in their fortunes?

Max Hendrick said abruptly, ‘There’s no need to look as if you’ve seen a ghost. You’ll get another job easily enough.’

‘It isn’t the job,’ she said mechanically. ‘It’s the flat—my family. I don’t know what we’re going to do.’

‘You have a family?’

‘My great-aunt and my young brother. My parents were killed in a road accident three months ago.’

He said incredulously, ‘Are you trying to tell me that you’re the breadwinner?’

She said defiantly, her mouth trembling a little, ‘They’re my family. They’re all I’ve got. I—I had to keep us together. That’s why a residential job seemed ideal, although the money was poor, but I was going to do some part-time typing to earn extra cash.’

Max Hendrick said slowly and very wearily, ‘Oh, my God!’ There was a silence, then he sighed, pushing his hair back from his forehead with an impatient hand. ‘I’m going to put some clothes on. Go downstairs and wait for me. Make a pot of coffee—strong coffee. You know how to do that?’

She flushed. ‘Of course, but …’

‘As I said before, no “buts”,’ he told her drily. ‘Can’t you even carry out a simple instruction without an argument?’

‘Yes,’ she said, hating him.

‘Then prove it.’ He took her by the shoulders and turned her towards the door.

Her mind was in ferment as she made the coffee. It seemed by his sudden change of attitude that she might be given another chance. But did she really want one? she asked herself. Was the fragile security they now enjoyed at Monk’s Dower really worth the cost of having to work for such an arrogant brute? She sighed, watching the coffee filter through into the jug beneath. Only time would tell—and did she really have a choice, anyway? Could she justify making Tim and Aunt Mary homeless again merely because of a clash of personalities?

She was standing by the window staring into the darkness when he came in. He looked at the jug of black coffee on the table with its attendant cream jug and sugar basin, and the single pottery mug, and his brows rose.

‘Won’t you join me?’

She shook her head. ‘Coffee in the evening keeps me awake.’

As if she was likely to sleep anyway, she thought bitterly.

He gave a slight shrug, then poured himself some coffee, tasted it and gave a slight nod. ‘Well, your coffee’s drinkable, so that’s one point in your favour at least.’

‘I’m sure all the minuses cancel it out,’ Ginny said quietly. ‘I’m sorry the house wasn’t ready for your arrival. It—it won’t happen again.’

‘I know it won’t,’ he said in a dry tone. ‘Because I intend to be here for quite some time. The question is—will you?’

‘That’s up to you.’ She would not meet his gaze, but stared down at the quarry-tiled kitchen floor.

‘And that’s tie devil of it,’ he said, half to himself. He was silent for a moment, then said abruptly, ‘Tell me about yourself.’

Taken aback, she said, ‘What do you want to know?’

‘Anything you care to tell me.’ He refilled his coffee mug. ‘I’d like to know primarily why you find yourself in this situation. It isn’t every day one comes across someone of your age looking after an old house in a backwater.’

‘I like housework,’ she protested. ‘And I don’t have the heavy cleaning to do. Mrs Petty does that.’

‘That’s hardly the point. You hardly fit the conventional image of a housekeeper.’ He gave the wall where the casserole had landed a long look. ‘An Olympic discus thrower, maybe.’

‘Haven’t you heard about the high level of unemployment?’ she tried to speak lightly. ‘You take what you can get and are thankful these days.’

‘And this was the best you could get?’ His glance was quizzical.

‘We needed somewhere to live,’ she said simply. ‘My father was heavily in debt when he died. Everything had to go, including our home. It isn’t easy finding a place when there’s a child involved.’

‘The young brother. How old is he?’

‘Eleven. And my great-aunt’s in her seventies. She would have—she offered to go into a home, but she’d have hated it. And they wanted to put Tim in care.’ She felt herself begin to shake at the old remembered nightmare. ‘I had to find an answer, and this seemed to be it.’

‘And have you no other family—no one who would have helped?’

‘I have an older sister,’ she admitted, realising with a shock that she had not given Barbie a thought until that moment. ‘She’s an actress. She’s appearing in a new play in the West End.’

‘Oh? Which one?’

Ginny wrinkled her nose in an effort to remember. ‘I think it’s called A Bird in the Hand.’

‘Oh, that one.’ His tone was neutral; Ginny couldn’t figure whether he spoke in praise or blame. ‘What’s your sister’s name? What’s yours, come to that? I don’t think Mrs Lanyon mentioned it.’

‘I don’t suppose she did,’ Ginny said wearily. ‘I’m Ginevra Clayton. My sister’s stage name is Barbie Nicholas—it was our mother’s maiden name,’ she added.

‘Yours would make a good stage name too.’

‘If I had any ambitions in that direction—and the talent to go with it, which I haven’t.’

‘No? Then in which direction do your ambitions lie, Miss Ginevra Clayton? I assume you don’t mean to spend your days as a junior Mrs Danvers. Marriage, I suppose, when the right man comes along.’

‘Perhaps,’ she said, also trying for a neutral tone, but she failed because involuntarily an image of Toby filled her mind, and the colour flared in her cheeks.

There was a pause, then he said very drily, ‘The more I hear, the more convinced I am that I should send you packing. Couldn’t this sister of yours put you up until you find somewhere?’

‘No.’ Her eyes sought his in dismay, but there was nothing for her comfort in his dark face. There was a remoteness about him, and even a suppressed anger suddenly.

She said in a subdued tone, ‘I’d better be going. Aunt Mary will be wondering where I am. Shall—shall I finish making your bed before I go?’

‘I think I can manage to add tie quilt unaided,’ he said flatly.

‘Very well.’ Ginny lifted her chin. ‘I’ll be over in the morning to see to the fires. Whatever you ultimately decide about me I—I shall continue to carry out the duties I’m being paid for until I leave.’