По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

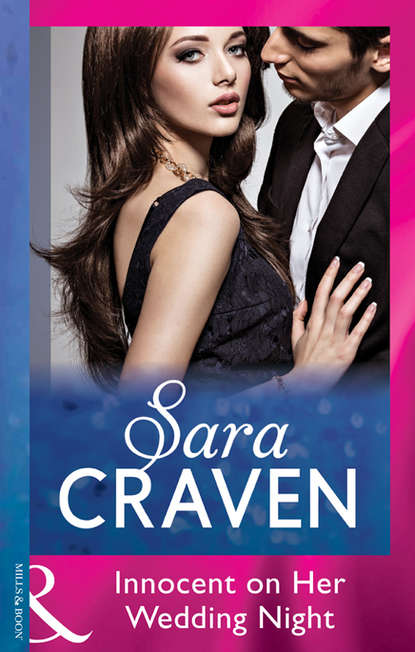

Innocent On Her Wedding Night

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Is that why you couldn’t be reached in Florida?’

No, she thought. That was because Andy hadn’t paid the rent on our office, and the landlord closed it down. But I didn’t know that at the time.

‘Jamie and I are brother and sister,’ she returned. ‘But we’re not joined at the hip.’

‘I can tell that,’ he said. ‘Sandra came as quite a surprise, didn’t she?’

‘Jamie’s had a lot of girls, and will probably have many more,’ she said. ‘It’s no big deal.’

‘I think,’ he said, ‘this one might be.’

‘Oh, really?’ Her tone was sarcastic. ‘You’ve been out of our lives for two years. Now you’re suddenly in my brother’s confidence? I don’t think so.’

‘You’re the one that’s out of touch, Laine. Jamie and I have been in contact quite a lot in recent months—one way and another.’

There was something about that—the phrasing, perhaps, or an odd note in his voice—which sent a prickle of unease down her spine.

Because on the face of it there was no need, or even likelihood, for their paths to cross. Jamie was a minor cog in a firm of City accountants. Daniel had inherited his family business empire and become a publishing magnate before he was thirty.

And, besides, he’d been Simon’s friend, she thought flatly, fighting the instinctive pain. No one else’s. Simon, her adored eldest brother, the golden boy, ten years her senior.

Daniel’s best mate at school from way back. Both high-flyers in the sixth form, members of the First Eleven at cricket, and demon tennis partners.

But there the resemblance ended. Because Daniel was a loner, the only son of a driven father who, after his wife’s death, had poured all his energies, all his emotions into work, into relentless expansion and acquisition, leaving little time to give to a small boy. In school holidays he’d been left to the mercies of paid staff, or farmed out to various business acquaintances with young families.

While Simon had had his mother, two younger siblings, and Abbotsbrook, that wonderful crumbling relic of a house with its huge untidy garden to come home to at the end of each term. A place where every summer gave the illusion of being filled with sun and warmth.

Eventually, grudgingly, Robert Flynn had agreed that his son could spend part of his holidays with his friend’s family.

After all, as Angela Sinclair had remarked, the house was always full of people. There were guests almost every weekend. One more would make little difference.

Except to me, Laine thought with a pang. It made all the difference in the world to me …

But that was forbidden territory, and she dared not go there. Particularly now.

She finished her coffee, and put the beaker on the floor. ‘Jamie’s well below your league, isn’t he? You always seemed to regard him as something of a pain. And you certainly can’t be short of places to live, so why here?’

‘It’s an arrangement that suited us both.’

‘And Cowper Dymond don’t have a New York branch,’ she went on. ‘So what’s Jamie doing over there?’

‘He’s working for me,’ Daniel said. ‘In the royalties section of Hirondelle Books.’

‘Working for you?’ Laine’s voice was incredulous, but her uneasy feeling grew. ‘But he had a perfectly good job. Why should he change?’

‘Perhaps that’s something else you should discuss with him?’ Daniel drained his coffee cup and rose. ‘He’s expecting your call.’

She stared up at him. ‘You’ve been talking to him? You told him I was here?’

‘While I was in the kitchen,’ he said. ‘I suggested that his room should be cleared, and the contents put into storage at his expense, and he agreed. Unfortunately, the removal firm I called can’t come until tomorrow, so you may have to spend the night on that sofa.’

‘You called?’ Laine lifted her chin. ‘I’m perfectly capable of making my own arrangements,’

‘You wish me to ring back and cancel?’ Daniel suggested pleasantly.

She wanted to say yes, but she knew it would be foolish, especially when he’d obviously pulled strings to get the job done quickly. And sleeping out here in the living room for any longer than was absolutely necessary had no appeal at all.

‘No,’ she said reluctantly. ‘Let’s leave things as they are.’

‘A wise choice,’ he approved. ‘You’re learning.’ He paused. ‘I have to go into the office for a couple of hours, so you’ll be able to pound your brother’s ears with your objections over my unwanted presence to your little heart’s content. Not,’ he added, ‘that it will make a blind bit of difference. The deal is done. But you might find it cathartic.’

He read the message conveyed by her over-bright eyes and compressed lips, and grinned.

‘And keep off that ankle,’ he advised. ‘You need it to heal quickly. So that you can start pounding the pavements instead.’

Knowing that he spoke nothing but the truth did nothing to improve her temper or calm the riptide of emotion threatening to overwhelm her as she watched him walk away and go into her bedroom—her bedroom—closing the door behind him.

A shudder ran through her. What a mess, she thought. What a blinding, unbelievable mess. And how in God’s name am I ever going to cope with it?

CHAPTER TWO (#u3d73b6e8-4152-5301-b598-c1f2c52f063a)

THE pain in her ankle was gradually turning to a dull throb. But the pain building inside her was a different matter. There was no quick fix for that, and it threatened to become unendurable more quickly than she could have imagined in her worst nightmares,

Yet she should have known, after these last two years of utter wretchedness. Months when she’d tried so hard to bury the hurt and bewilderment in the deepest recesses of her mind. And forget him.

Attempts that had never worked. That had eventually convinced her that only a complete change in her circumstances would do.

Which was why she’d made the reckless decision to relocate to Florida, without fully considering all the implications. Because she’d seen Andy’s proposition as a chance for rehabilitation—a way of turning her life around and making a new start.

With an ocean—a whole continent—between Daniel and herself, she’d reasoned wildly, she might just stand a chance …

But now, after only just over a month, she was back, and in a worse situation than before. And shock and anger were fast giving way to total desperation as she contemplated what the weeks ahead of her would hold.

Seeing Daniel each day, she realised, her throat tightening. Knowing that he was sleeping only a matter of yards away every night. Oh, dear God …

She had a sudden image of him as he’d been that night, two years ago, his tanned skin dark against the white towelling bathrobe, his face stark with disbelief in the moonlight as she’d told him, over and over again, her voice small and raw, the words stumbling against each other, that their marriage only a few hours earlier had been a terrible—a disastrous mistake. And that it was finished—over and done with—even before it had begun.

Forcing him to accept that she meant every word, and that there would be no second chance. Until at last he’d believed her, and turned away in bitter condemnation.

But he’d done as she wished. The marriage had been dissolved, more quickly and quietly than she’d believed possible.

What a strange word ‘dissolved’ was to use in the context of ending a marriage, she thought. It sounded almost gentle, implying that the relationship had been made to vanish, like rain falling on the earth. Not the agonised tearing apart—the destruction of her hopes and dreams—that had really taken place.

Nor had it led to Daniel simply disappearing from her life, as she’d hoped. Because once Laine had started living and working in London he’d been only too much in evidence.

She’d glimpsed him in the distance across crowded rooms. Looked down from the circle of a theatre to see him in the stalls, or discovered his picture in some paper or magazine. Never alone, either. The parade of his women seemed unending. Although, as she’d reminded herself wretchedly, that was only to be expected.

After all, he was a free man, in a way that she would never be a free woman. Because his heart had not been broken, or his life shattered, as hers had been.