По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

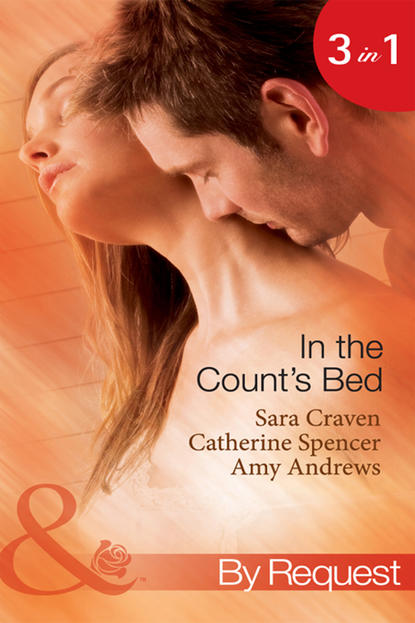

In The Count's Bed: The Count's Blackmail Bargain / The French Count's Pregnant Bride / The Italian Count's Baby

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘The family that, according to my aunt, does not exist.’

Laura groaned inwardly. Paolo had reacted with ill temper to her confession that she’d deviated from the party line.

She made herself shrug. ‘I can’t imagine where she got that idea. Perhaps it suited her better to believe that I was a penniless orphan.’

‘Which, of course, you are not.’

‘Well, the penniless bit is fairly accurate. It’s been a real struggle for my mother since my father died. I’m just glad I’ve got a decent job, so that I can help.’

The dark brows lifted. ‘Does working in a wine bar pay so well? I did not know.’

But that’s not the day job. The words hovered on her lips, but, thankfully, remained unspoken.

Oh, God, she thought, hastily marshalling her thoughts. I’ve goofed again.

She met his sardonic gaze. ‘It’s a busy place, signore, and the tips are good.’

‘Ah,’ he said softly. He glanced around him. ‘So, what are your impressions of Besavoro?’

‘It’s larger than I thought, and much older. I didn’t think I would catch more than a glimpse of it, of course.’

‘I thought you would be pleased that I sent Giacomo away for another reason,’ he said, leaning back in his chair, and pushing his sunglasses up onto his forehead. ‘It will mean that Paolo will get his medicine more quickly, and maybe return to your arms, subito, a man restored.’

‘I doubt it.’ She looked down at the table. ‘He seems set for the duration.’ She hesitated. ‘Has he always fussed about his health like this? I mean—he’s simply got a cold.’

‘Why, Laura,’ he said softly. ‘How hard you are. For a man, no cold is ever simple.’

‘Well, I can’t imagine you going to bed for a week.’

‘No?’ His smile was wicked. The dark eyes seemed to graze her body. ‘Then perhaps you need to extend the scope of your imagination, mia cara.’

I am not—not going to blush, Laura told herself silently. And I don’t care how much he winds me up.

She looked back at him squarely, ‘I meant—with some minor ailment, signore.’

‘Perhaps not.’ He shrugged. ‘But my temper becomes so evil, I am sure those around me wish I would retire to my room—and stay there until I can be civil again.’

He paused while Luigi placed the coffees in front of them. ‘But I have to admit that Paolo was a sickly child, and I think his mother plays on this, by pampering him, and making him believe every cough and sneeze is a serious threat. It is her way of retaining some hold on him.’

‘I’m sure of it,’ Laura said roundly. ‘I suspect Beatrice Manzone has had a lucky escape.’ And could have bitten her tongue out again as Alessio’s gaze sharpened.

‘Davvero?’ he queried softly. ‘A curious point of view to have about your innamorato, perhaps.’

‘I meant,’ Laura said hastily, in a bid to retrieve the situation, ‘that I shan’t be as submissive—or as easy to manipulate—as she would have been.’

‘Credo,’ he murmured, his mouth twisting. ‘I believe you, mia cara. You have that touch of red in your hair that spells danger.’

He picked up his cup. ‘Now, drink your coffee, and I will take you to see the church,’ he added more briskly. ‘There is a Madonna and Child behind the high altar that some people say was painted by Raphael.’

‘But you don’t agree?’ Laura welcomed the change of direction.

He considered, frowning a little. ‘I think it is more likely to have been one of his pupils. For one thing, it is unsigned, and Raphael liked to leave his mark. For another, Besavoro is too unimportant to appeal to an artist of his ambition. And lastly the Virgin does not resemble Raphael’s favourite mistress, whom he is said to have used as his chief model, even for the Sistine Madonna.’

‘Wow,’ Laura said, relaxing into a smile. ‘How very sacrilegious of him.’

He grinned back at her. ‘I prefer to think—what proof of his passion.’ He gave a faint shrug. ‘But ours is still a beautiful painting, and can be treasured as such.’

He drank the rest of his coffee, and stood up, indicating the postcards. ‘You wish me to post these? Before we visit the church?’

‘Well, yes.’ She hesitated. ‘But you don’t have to come with me, signore. After all, I can hardly get lost. And I know how busy you are. I’m sure you have plenty of other things to do.’

‘Perhaps,’ he said. ‘But today, mia cara, I shall devote to you.’ His smile glinted. ‘Or did you think I had forgotten about you these past days?’

‘I—I didn’t think anything at all,’ she denied hurriedly.

‘I am disappointed,’ he said lightly. ‘I hoped you might have missed me a little.’

‘Then maybe you should remember something.’ She lifted her chin. ‘I came to Besavoro with your cousin, signore.’

‘Ah,’ Alessio said softly. ‘But that is so fatally easy to forget, Laura mia.’

And he walked off across the square.

The interior of the church was dim, and fragrant with incense. It felt cool, too, after the burning heat of the square outside.

There were a number of small streets, narrow and cobbled, opening off the square, their houses facing each other so closely that people could have leaned from the upper-storey windows and touched, and Laura explored them all.

The shuttered windows suggested a feeling of intimacy, she thought. A sense of busy lives lived in private. And the flowers that spilled everywhere from troughs and window boxes added to Besavoro’s peace and charm.

‘So,’ Alessio said as they paused for some water at a drinking fountain before visiting the church. ‘Do you like my town?’

‘It’s enchanting,’ Laura returned with perfect sincerity, smiling inwardly at his casual use of the possessive. The lord, she thought, with his fiefdom. ‘A little gem.’

‘Si,’ he agreed. ‘And now I will show you another. Avanti.’

Laura trod quietly up the aisle of the church, aware of Alessio following silently. The altar itself was elaborate with gold leaf, but she hardly gave it a second glance. Because, above it, the painting glowed like a jewel, creating its own light.

The girl in it was very young, her hair uncovered, her blue cloak thrown back. She held the child proudly high in her arms, her gaze steadfast, and almost defiant, as if challenging the world to throw the first stone.

Laura caught her breath. She turned to Alessio, eyes shining, her hand going out to him involuntarily. ‘It’s—wonderful.’

‘Yes,’ he returned quietly, his fingers closing round hers. ‘Each time I see it, I find myself—amazed.’

They stood in silence for a few minutes longer, then, as if by tacit consent, turned and began to walk around the shadowy church, halting briefly at each shrine with its attendant bank of burning candles.

Laura knew she should free her hand, but his warm grasp seemed unthreatening enough. And she certainly didn’t want to make something out of nothing, especially in a church, so she allowed her fingers to remain quietly in his.

But as they emerged into the sunshine he let her go anyway. Presumably, thought Laura, the Count Ramontella didn’t wish ‘his’ citizens to see him walking hand in hand with a girl.