По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

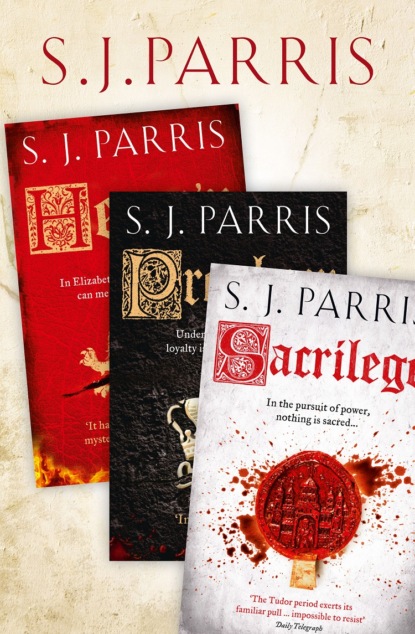

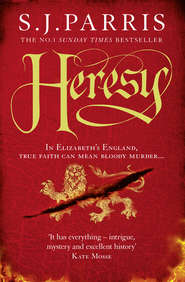

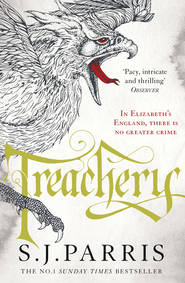

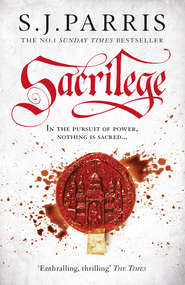

Giordano Bruno Thriller Series Books 1-3: Heresy, Prophecy, Sacrilege

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I can’t see another explanation,’ I said, looking again at the dog’s fearsome teeth, through which its limp tongue now lolled, spittle hanging in tendrils from its jaws. Norris’s arrow stuck upright from its gullet. ‘Someone who knew Doctor Mercer would come here at this hour. But surely he never suspected any harm would come to him, else he would have armed himself.’

Then I remembered Mercer’s strange remark the previous night, about how we might all live differently if we saw death approaching. I had dismissed it, but had he been revealing that he feared for his life? Unhappy coincidence only, I guessed; besides, he had spoken confidently of attending the disputation, and of conversing with me later. I felt a sudden awful sorrow; though I hardly knew the man, he had seemed warm and genuine, and I had stood by only minutes ago and listened to him die. To think that he might have been saved if I had acted quicker, if someone had had a key, if Norris had arrived sooner with his bow. One moment of indecision decides a man’s fate, I thought, and realised that I too was trembling.

‘Was it perhaps his regular practice to walk in the garden so early?’ I asked. ‘I mean, could someone have known to expect him here?’

‘The Fellows often like to read in the quiet of the Grove,’ the rector said. ‘Though not usually at this hour, I grant you – it is too dark. The undergraduates usually rise at half past five to make themselves ready before chapel at six – morning service is compulsory. There is rarely a soul abroad in the college any earlier, not even the kitchen servants. I confess I have never walked in the garden at such an hour so I could not say if any of my colleagues had the habit of doing so.’

As I bent again to Mercer’s body, separating the bloodied and torn clothes to see if anything on his person might explain his presence in the Grove so early, I remembered how he had joked about the garden being popular for trysts. Had he been expecting someone who never came, or who came and brought death with them? He carried no book, but a bulge inside his doublet suggested a hidden pocket; reaching in, I withdrew a fat leather purse that jingled with coins.

‘If his purpose was a quiet, contemplative walk before sunrise, surely he would not have needed to bring this,’ I said, untying the purse and showing the rector its contents. The English coins meant nothing to me, though there were clearly a lot of them, but the rector’s eyeballs bulged at the sight.

‘Good God, there is at least ten pounds here!’ he exclaimed. ‘Why would he carry such a sum?’

‘Perhaps he expected to meet someone to whom he owed money.’

‘And knowing he would be here, they set a dog on him!’ he exclaimed, his eyes wide. ‘Revenge for a bad debt, that must be it.’

I shook my head.

‘Then why is the money still in his pocket? If someone had wished to harm him for failure to pay a debt, surely they would have made sure to take the money first?’

‘But who would ever have meant to harm Roger?’ asked the rector in despair.

‘I cannot say. But a wild dog does not get into an enclosed garden through locked gates by accident.’ I brushed down my clothes, realising that they were now stained with Mercer’s blood. ‘I suppose now that this terrible thing has happened, Rector, you will want to cancel the disputation this evening?’

The rector’s face filled with fear again.

‘No!’ he said fiercely, gripping my shoulders. ‘The disputation must go ahead. We cannot allow this incident to disrupt a royal visitation – can you imagine the consequences, Doctor Bruno? Especially if it were rumoured to be –’ he glanced around before whispering the word – ‘deliberate. The college would be tainted and my reputation with it, and we have already had so much trouble here lately, I fear Leicester’s displeasure more than I can tell you.’

‘But a man has been brutally killed – perhaps murdered,’ I protested. ‘We cannot go about our business as if nothing has happened.’

‘Shh! For the love of Christ, do not repeat that dreadful word murder, Bruno.’ The rector looked frantically about the garden and lowered his voice, though we were alone. ‘We will have it announced that this was a tragic misfortune – we shall say …’ he paused briefly to compose his story ‘… yes, we shall say that the garden gate was left open and a stray dog got in and attacked Roger, who had got up early to pray and meditate in the Grove.’

‘Will this be believed?’

‘It will if I say it was the case – I am the earl’s appointed rector,’ said Underhill, a touch of his old pomposity returning. ‘Besides, it was dark and misty and no one saw clearly.’ There was a hardness in his face now, and desperation; I saw then his determination to preserve the college’s good name at any price, and imagined this same ruthlessness must have ruled him during the trial of the hapless Edmund Allen.

‘But the locked gates—’ I protested.

‘Only you and I know about the locked gates, Bruno. I see nothing to be gained from mentioning them at present, if you wouldn’t mind.’

‘What about the porter? Will he not remember checking the gates at night?’

The rector gave a dry laugh.

‘I see you are not acquainted with our porter. A clear head and a sharp memory are not his strong points. If I say a gate was left open, he could not for certain claim otherwise. No, I think this is our safest course.’

Seeing my look of concern, he squeezed my shoulder and added, in a lighter tone, ‘If all suspicion is hushed up, it will be the easier to investigate what really happened here this morning. But if there is a great fuss, and all Oxford is abuzz with the idea that Lincoln is a place of savage murder, the perpetrator – if indeed there is a perpetrator – will surely disappear in the hubbub. If justice is to be served, we do best not to shout this tragedy from the tower. I would be most grateful for your help in this matter, Doctor Bruno.’

I was not sure whether he meant the matter of disguising the truth or of uncovering it, but I was sorely troubled by the thought that I may well have been the last person to see Roger Mercer alive, and that whoever had planned his vicious end was at that moment at liberty somewhere in Oxford, perhaps exulting in his success. The rector’s cold briskness had shocked me, too; his human response to his colleague’s awful death seemed swallowed up in fear for his office.

The sky had grown paler and the mist was thinning, lingering only in ragged shreds among the trees. The two corpses in the dewy grass had acquired a stark solidity with the grey light. The rector glanced up anxiously.

‘Dear God – it is almost time for chapel! I must be there to speak, reassure the community. Already the story will be growing.’ He twisted his fingers together until the knuckles turned white, speaking as if to himself. ‘First I must order the kitchen servants to bring a sack for that carcass. It cannot stay here.’

I stared at him, appalled, until he noticed my expression.

‘The dog, Bruno! But you are right – the coroner must be fetched before the body can be removed. Oh, there is too much to do! I will have to ask Roger—’ Then he clapped his hands to his mouth and turned back to look at the corpse, as if only now comprehending the loss of his deputy.

‘Oh, God,’ he whispered. ‘Roger is dead!’

‘That’s right,’ I said, watching him absorb the truth of it.

‘But then – this means there will have to be another congregation, another election for sub-rector, and there is no time to convene – but in the meantime I must have someone to act under me, and that will occasion all the usual petty jealousies and ill-feeling, just when we do not need them – oh, how could this have come to pass?’ Trying to contain his mounting fears, he turned to me with an earnest expression, his hands flapping helplessly at his sides. ‘Doctor Bruno – this is a dreadful thing to ask of a guest, I know, but would you stay with poor Roger’s body until the coroner can be brought? I must make the sad announcement of this morning’s events in chapel in such a way that quiets the reports of it, if that is possible. Keep the students out – we do not want them crowding in here to satisfy their ghoulish curiosity as if it were a bear-baiting.’

‘Of course I will stay,’ I said, hoping my vigil would not be a long one; though I am not superstitious about the dead, the empty stare of Roger Mercer’s sightless eyes seemed to accuse me for my failure to help him. Our fears are all for our poor, weak flesh, he had said the night before. Now he had looked that fear full in the teeth; I still remembered his cracked voice crying to Jesus and Mary to save him.

The rector scuttled off across the grass in the direction of the courtyard, and I was left alone with the bodies and my whirling thoughts. While I waited for them to settle into some semblance of order, I bent again to Mercer’s corpse and lifted what remained of his tattered gown to cover his ravaged face. Superstition says that the eyes of a murder victim retain the image of his killer, but as I looked at Mercer’s terrified stare for the last time I thought: if such foolishness were true, would I see the image of the great dog? But the fact of the locked gates stubbornly persisted; the dog was not Mercer’s true killer, only his agent. I moved again from the sub-rector’s body to the dog’s to examine it. It was a huge brute, the height of a man’s waist upright with a long, narrow head. I noted again how thin it was, though it did not look otherwise abused. Whoever had loosed this dog in here must have planned the event carefully, increasing the force of the attack by keeping it desperately hungry for some days beforehand, by the look of it. And Mercer’s heavy purse – which the rector had taken – suggested he had been expecting to meet someone to effect some kind of transaction. But if the money had been at the centre of some dispute in which Mercer had fallen out with someone so badly that they could wish to kill him, I could not fathom why the purse had been left. It would seem that the money had been less of a priority than the sub-rector’s death, though it must have been key to the meeting he anticipated.

I considered again the layout of the garden. It was abutted on the north side by the kitchen part of the way, though I could see no door from the kitchens into the garden. On three sides it was enclosed by a wall at least twelve feet high, and on the fourth it adjoined the east range of the college, the side of the quadrangle that housed the hall and the rector’s lodgings. I presumed Mercer had entered the garden through one of the two passageways either side of the hall, letting himself in with his own key. Had he then locked the gate behind him, so as not to be disturbed, or had someone waited for him to enter before locking the door from the college side, leaving him unwittingly shut in? Could that have been the same person who then opened the gate from the lane through which the dog – presumably muzzled until the last moment – had been released, locking that behind the animal? But it would have taken a good few minutes to run out of the main gate and around the side of the building, and anyone doing so would have been seen by the porter – assuming he had been awake.

From the courtyard a bell tolled dismally to rally the scholars to chapel, where the rector would spread his benign reassurance and dispel the young men’s more lurid imaginings. As I rose to my feet, I wondered idly if James Coverdale would finally achieve his ambition of becoming sub-rector, and a thought struck me like a cold blade. The rector had asked, rhetorically, who would want to harm Roger Mercer, and I had replied that I had no idea. But now that I considered the proposition I realised that even I, a stranger who had not been in the college one full day, had already encountered two people who apparently hated him. Might there not be more? Perhaps one of them tried to extort money from him and decided instead to kill him. I had found him a genial enough man, but it seemed his part in the trial of the unfortunate Edmund Allen had aroused resentment; who was to say how many other enemies he might have made? But these resentments must have simmered for a long time; why wait until the week of a royal visitation to act on them? Unless—

I was interrupted in my pursuit of this new trail by the sight of a figure running towards me through the trees from the direction of the college; I stepped forward in the hope that the coroner had arrived to relieve me of my duties, and was surprised to recognise Sophia Underhill, dressed in a thin blue gown with a shawl around her shoulders, her hair flying out behind her. She halted a few yards away, looking equally surprised to see me.

‘Doctor Bruno! What – what are you doing in here?’

‘I was – waiting for your father,’ I said, taking another step towards her in the hope of guiding her away from the two corpses.

‘They said Gabriel Norris shot down an intruder,’ she said, her face flushed with the drama of the moment. ‘Is he still here?’ Her eyes were bright with eager anticipation as she looked around wildly, but I noticed she was twisting her hands together in agitation in the same manner as her father.

‘Not quite.’ I almost smiled; despite the rector’s best efforts, it seemed the tale was already growing in the telling. ‘You have not spoken to your father?’

‘He is at morning prayers in chapel – I heard the news from two scholars who were running there late,’ she said, peering past me to where the shapes lay in the dense grass. ‘Of course we heard all the noise from our windows but I never imagined – is that the thief’s body there?’ She seemed keen to take a look; I planted myself firmly in her path.

‘Please, Mistress Underhill, you must keep back. It is not a sight you should see.’

She tilted her head and stared at me defiantly.

‘I have seen death before, Doctor Bruno. I have seen my own brother with his neck broken, do not treat me like one of these pampered ladies who has never been out of a parlour.’

‘I would not dream of it, but this is worse,’ I said, holding my arms out absurdly as if this might obscure the sight. ‘Well, not worse than one’s brother, I don’t mean – I mean only, it is very bloody, not something a woman should see. Please trust me, Mistress Underhill.’

At this she snorted, and placed her hands on her hips.

‘How is it that men think women are too frail to look on blood? Do you forget we bleed every month? We push out babies in great puddles of gore, do you imagine we hide our eyes when we do that, in case it offends our delicate senses? I promise you, Doctor Bruno, any woman can look on blood with more fortitude than a soldier, though men think we must be treated like Venice glass. Do not be one more who wants to wrap me up in linen and keep me in a box.’

I was surprised by the ferocity of her argument, and conceded that she had a point; even so, I had been charged with protecting Mercer from prurient eyes, so I stepped forward again until I was standing directly in front of her, only a few inches away. It was disconcerting to find that she was almost as tall as me.