По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

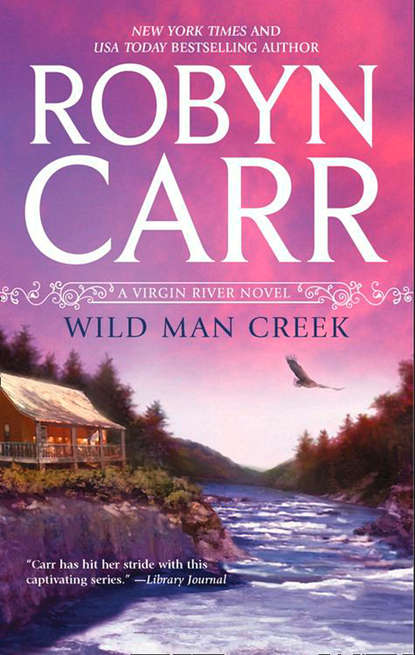

Wild Man Creek

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Still can’t get the best out of that arm, huh?” Luke asked, nodding toward the affected limb.

“It’s coming along. It’s the elbow, man. It might never be right. The breaks in the humerus seem okay now, but I went through a shoulder problem from—never mind all that. I’ll take the rifle if that’s all you have.”

“I have a Magnum locked up, but the thing is, if you shoot a bear with it, you might only piss him off.”

“The noise could scare him away, though,” Colin said.

“Hmm, yeah,” Luke said with a tilt of his head. “I haven’t fired it in a while. You’ll have to clean it, fire it, make sure—”

“Great, thanks, uhh …” Colin said. Then he smiled a bit lamely and said, “My buddy Brett seems to be very relaxed, sitting here on my lap. I think he’s going to need a little change. You might want to brace yourself.”

Colin had rented himself a pretty good little cabin. Furnished, but not fancy; electricity and indoor plumbing. It was lacking a few things—good, natural light, for one. When Colin had looked at it with Aiden the previous month, he lamented the dark shadows in the cabin, but he could live with that. He brought bright lights with him to illuminate the place for those days when it was too wet to paint outside. He looked forward to taking his painting, his easel, canvas and paints to a higher spot outdoors, to a clearing, and taking advantage of the good, natural light when the weather permitted. What the cabin did have was a quiet, secluded space in the forest with a creek. Or brook. Or whatever you called a baby river. That meant wildlife. And wildlife was what Colin wanted.

Colin had always been a gifted artist, but it had never interested him as much as flying and sports. He’d always doodled; in high school he was the one stuck with all the posters, signs, lettering, even chalk renderings of team players. High school counselors and art teachers wanted him to go to college to study art, but he’d been after something a lot more exciting.

It was ironic that Colin had wanted to fly since the first time he looked into the sky and saw aircraft above him, and yet Luke was the first in their family to do it. Luke always remarked that Colin followed him into Black Hawk helicopters, but that was not so. Luke had gone into the Army ready for any assignment from artillery to KP when he was offered a Warrant Officer School slot and from there flight school. Luke had stumbled into a flying career. Colin had dreamed of flying jets or helicopters since he’d been about six years old; he had enlisted with that as his single objective. He couldn’t wait to get off the ground!

Art was his sideline, just as it had been in high school. He was good at caricature and entertained his Army buddies with his drawings. He’d done an oil portrait of the five Riordan boys, ages ten to eighteen; he’d copied it from a photo and given it to his mother. He’d painted a huge, wall-size mural of a Black Hawk in a house he’d owned about ten years ago and when the new owner bought it he swore he’d keep it on that wall forever. But all that had been for fun. While in treatment—all kinds of treatment—he’d been drawing and painting. Ballroom dancing or squash certainly weren’t options for rehab.

The injuries Colin sustained from the crash led to addiction to Oxycontin, which led to being arrested for buying from a dealing doctor, which led to addiction treatment, which led to depression, which led to … Put all the pieces together and he’d been in one form of therapy or another for six months. Colin had been painting with oils, watercolors and acrylics for a few months now, one of the only parts of his past he’d been able to hang on to and something that was now part of his therapy. It slowed him down enough to let his mind move easily rather than crazily. He’d painted all the bowls of fruit and landscapes he could stand, but the thing that got his juices flowing was painting wildlife.

He was frighteningly good at it for a man who hadn’t been professionally trained. He could replicate some of the best wildlife portraits he found; then he discovered his own images through the lens of a camera.

He had taken one, and only one, professional art instruction in his life after high school and that was in the nuthouse. He went from the hospital to physical therapy to drug rehab to depression rehab—and it was in the third rehab that some wise guy counselor suggested a bona fide art instructor, since painting had become so crucial to Colin’s recovery.

The art instructor had said, “The hardest part of training a painter is showing him how to introduce emotion into his work, and you do it naturally.”

And Colin had said, “Don’t be ridiculous—I don’t have emotions anymore.”

After repeating this to his assigned counselor, they had decided to slowly reduce and eliminate the antidepressants and increase the group therapy sessions. To that idea Colin had said, “Can’t you just shoot me instead?”

It had worked in spite of Colin’s dislike of those touchy-feely group-hug sessions. He must have been ready to come off the antidepressants. Now he was glad; his senses were no longer dulled by drugs of any kind.

He’d never even considered art as a career. But why would he? He was into fast, edgy living; he was a combat-trained Black Hawk pilot who lived hard. He drove a sports car too fast, occasionally partied too much, played amateur rugby, had too many women, went to war too often. And then it all came crashing down on him, literally. In slowly learning to pick up the pieces of his lost life, he reclaimed his art. Art moved slow and exercised feelings he had been able to ignore for a long time.

Now, after many long months, he was released to pursue his continued healing and his art. He had a good digital camera with an exceptional zoom lens. Obviously wildlife couldn’t pose for him—but he could catch them in the wild, get several photos and work from them.

Though he wouldn’t admit it to anyone, Colin was looking forward to really getting into his art and to reclaiming the life he had nearly lost.

As promised, Luke helped Colin get the internet up and running, talking a little more than he used to. It was probably the influence of living with a woman. Colin recalled that most women had that talking gene hardwired.

Colin spent the next couple of days cautiously prowling around the forest, confirming to himself that he’d made a good choice. He liked the quiet; he enjoyed the sounds in the woods. He liked to sit on his rough-hewn porch at dawn and dusk, still and quiet, camera at the ready, and watch the wildlife that would gather at the creek—everything from a black bear fishing for trout to a puma looking for a drink. He caught a good shot of a fox; a distant photo of a buck; the head of a doe peeking out of the brush; an amazing American eagle in flight.

He went out exploring, rain or shine, but was careful with his hiking, and since spotting the bear fishing in his creek, never went out without the gun. He watched his step and moved slowly; he wasn’t kidding about the second titanium rod. He had no interest in breaking any more bones.

Being outdoors in the crisp March spring was energizing for him. It seemed to drizzle two out of three days, but although he couldn’t paint outdoors in wet weather, Colin certainly didn’t mind being exposed to the elements. And watching the new spring growth begin to emerge was a new experience for him. He’d never noticed things like new vegetation, the quality of the air and the perfect stillness of the forest before now. He’d never moved slow enough to take notice.

On a rare sunny day he took his easel and paints and drove up an old dirt road past a vineyard and a couple of farms. He set up in a meadow and went back to work on the eagle he had started a few days ago. He clipped his photo to the top of the canvas and found himself wondering, What does it feel like up there? Tell me what it’s like to know you can just step off a limb and soar …

Just then he heard a wild rustling in the trees not far away. He put down the palette and brush and pulled the .357 Magnum out of his belt at the small of his back. He took a stance in the direction of the noise, his pulse picking up speed, and aimed in the direction of the sound. But the creature who broke through the trees was not a black bear. It was a girl in sweatpants, red rubber boots, a dirty tee T-shirt and ball cap with her ponytail strung through the back. He knew it was a girl by her vaguely female shape and her deafening scream as she dived to the ground, facedown, with her hands over the back of her head.

Colin calmly engaged the safety and tucked the gun back in his belt. “It’s all right,” he said. “I’m not going to shoot you. You can get up.”

She lifted her head and looked up at him. “Are you crazy?”

Now there were some pretty big brown eyes, he thought. Very pretty. “Nope. Not crazy. I was expecting a bear.”

She lifted herself up slowly, sitting back on her heels. “Why in the world were you expecting a bear?” she demanded.

“They’re starting to come out of hibernation now, with cubs. I’ve seen a couple. Thankfully at a safe distance.”

She huffed. “Don’t you know they’re more afraid of you than you are of them?”

He smiled lazily. “Better to be safe. On the off chance I’m not that scary,” he offered with a shrug. He bent to pick up his palette and brush.

“Amazing,” she said with an irritated tone. “I have yet to hear anything that sounds like an apology!”

She was really pissed, and for some reason, it made him smile. He tried to keep it a small smile, asking himself why he found her so amusing. He gave a half bow, partly to conceal his grin. “Sorry if I startled you,” he said. “And sorry you startled me. You weren’t in any danger—I wouldn’t shoot something I couldn’t positively identify.”

“Very lame attempt,” she said. “What are you doing here?”

All right, he was standing in front of an easel, holding a paint palette and brush. “Taxidermy?” he responded with just a touch of his own sarcasm.

She stood and brushed at her dirty sweatpants. “Cute,” she said. “Very cute. I mean, on my property?”

“Oh, this is yours? The roads were open and there were no signs. The light’s good here. My place is buried in the forest where it’s pretty dark—all I have is artificial light. If this is a problem, I’ll move on ….”

“But how did you get here? Where is the road? Because this is my—I mean, I don’t own it, but I rent that house back there,” she said, pointing over her shoulder where the top of a large Victorian could be seen above the trees. “And aside from cutting down some trees, I couldn’t figure out how to get to this clearing back here. I could see it from the widow’s walk, but there didn’t appear to be any access.”

“And yet, here you are,” he pointed out with a smile. “Posing as a bear.”

She brushed at her cheeks, which only moved the dirt from her hands onto them. But Colin was taking closer stock of her and starting to see things he’d missed when she first burst through the trees and threw herself to the ground. Like a very delicious female shape—lean and sexy but with curves in all the right places, and a lot of chestnut-colored hair that was escaping that ball cap to fan her face. Her lips were full and peachy; her skin like ivory with a few light freckles across her nose; those eyes were amazingly large and deep and shadowed by thick lashes. He had a sudden urge to taste that mouth, that smart, sassy mouth.

“It wasn’t easy,” she said. “I plowed through those trees and bushes to ask you how you got here with all your stuff.” She turned up a palm; it was bleeding. “See, the last owner let the trees and shrubs between her backyard and this clearing grow in, and I wanted to get back here with gardening equipment, but I couldn’t see how …”

He looked at her palm, looked her up and down and asked, “Was it really dirty coming through there?”

“Huh? Oh!” she laughed. “I’ve been gardening. I mean, farming—you can’t call what I’ve been doing gardening. I’ve gone a little nuts. See, stuff is already coming up. I’ve looked up the planting cycle online and if I hurry I can catch up. I have to get all my seeds and starters in the ground before April, and that actually puts me a little behind. Vegetable seeds should be in the ground early March; tomatoes should be started. Except the squashes and melons—there’s time for them yet. And I’ve already had birds, deer, rabbits—”

He took a step toward her. “What are you doing about them?” he asked.

She shrugged. “I have a horn. A cow horn. It’s loud. The birds fly, the deer run. But I hate it. I don’t hate scaring off birds so much, but the doe come with their fawns and I don’t really want them to go, but if I don’t scare them off and they dig up the garden, all my work is for nothing. And the only reason to garden is to watch it grow. Deer trampling my new plants isn’t going to get me—”

“Don’t you garden to eat it or sell it?” he asked.

“Honestly, I haven’t thought that far ahead. Right now I garden to garden.”

He took a step toward her. He stuck out a hand. “Colin Riordan,” he said.