По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

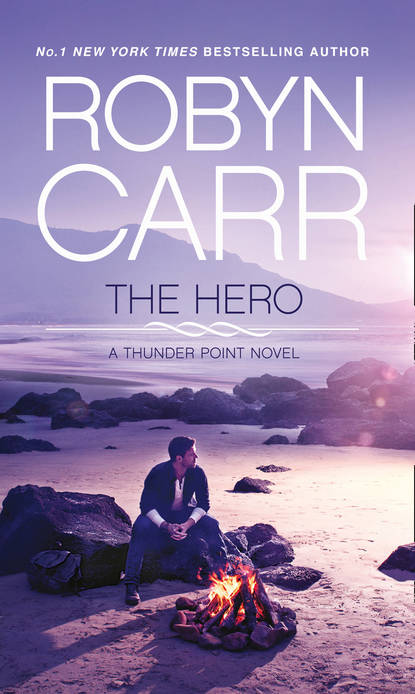

The Hero

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Well, Rawley, I think you like having them around,” Sarah said.

Rawley shrugged. “It’s okay. I never thought I’d know what it felt like to be a grandpa.” He shrugged again. “I don’t hate it.” Then he turned and went back into the kitchen.

Sarah, Landon and Cooper exchanged smiles.

Rawley brought a second rack of clean glasses into the bar and Sarah said, “So—has your cousin looked for work around Thunder Point?”

“Not that I know about. You got something?”

“No. But Saturday is Dr. Grant’s open house for his new clinic. You should bring her. It’s not exactly a job fair, but everyone in town will be there. She could talk to people. Find out if anyone knows of any jobs or any child care or babysitting. In fact, maybe someone needs child care or babysitting. Wouldn’t that be convenient?”

Rawley thought about that for a minute. Then he said, “I’ll tell her. But I’m not much for parties or a lot of people.”

“Tell her, I’d be glad to take her,” Sarah offered. “I wouldn’t miss it.”

* * *

Devon hadn’t had a typical childhood, but it had been a safe and happy one. Devon’s mother, Rhonda, was a nurse who became close to her neighbor, Mary. Mary immediately took Rhonda under her wing knowing Rhonda was pregnant and alone. And since Mary was a day care provider working out of her home, it only followed that after Devon was born, Mary watched her while Rhonda worked. And Rhonda named Mary as Devon’s guardian, should anything happen.

And something did indeed happen. Poor Rhonda was struck by a drunk driver as she waited at the bus stop on her way home from work one evening. Devon had been only nine months old.

Devon knew Aunt Mary was not her real aunt, was not her mother’s older sister. What she didn’t know was that Mary waited tensely for years for some distant, unknown family member to appear and lay claim to Devon. She clung to that will and birth certificate with a miser’s zeal, ready to do battle with anyone who might try to take the little girl away.

Mary was old enough to be Devon’s grandmother, but she was a popular figure in the neighborhood, at their church and in Devon’s schools. She was kind, nurturing, energetic and helpful, and Devon’s friends had always loved her—especially the pizza parties and sleepovers. Mary was a great volunteer and she took responsibility as any parent would, participating in field trips and fund-raising, and when Devon was a cheerleader or on a team, Mary had never missed a game or meet. Never.

Mary had always told Devon she had pluck. And that she was tough. She was a survivor. She said the same things even when crises like Devon not making the championship girls volleyball team, or junior varsity cheerleading squad, or having to make do with a partial scholarship, instead of getting the big one. “I just won’t make it,” teenage Devon had wailed.

And Mary had said, “Girl, you will rise above this, and fast. You’re strong. Do you have any idea how many times people have to start over and make a new path? For myself, I can’t count the number of times! I buried two husbands before you were born! Lost the first in Vietnam and the second to cancer! And just when I thought my life would slide gentle into old age, who comes along but Miss Devon!” And then she would laugh and laugh. “The Lord blesses me with work and new ideas every day of my life!”

So Devon had grown up with a devoted parent and a house full of small children who were picked up by their parents by five. With the help of scholarships and part-time jobs, she’d attained a degree in early childhood education and had begun work on her Master’s when Mary first fell ill. Very ill. That’s when Devon had said, “I don’t have enough pluck for this. I’m not that strong.”

“You are if you want to be,” Mary had said. Not long after her hospitalization and subsequent death came Devon’s dark, frightening period when there was no work, not enough money for rent and the constant worry about how she would make it through the next day. She constantly reminded herself—I’m a smart, educated, hardworking person—how does this happen? She needed a miracle.

What do you need, sister? Tell me. Maybe I can help.

Why wouldn’t she love Jacob? Why wouldn’t she take to his Fellowship? She’d grown up helping to tend other peoples’ children and all she’d ever really wanted was a family of her own. Perhaps this was an unusual family by normal standards, but at least she felt safe and invulnerable. And she fell for Jacob, as did everyone else—he was not only sweet and kind but also commanding. Powerful. Charismatic. There was little doubt in her mind he was strong enough to keep all of them safe. He was just the miracle she thought she needed.

Little Mercy was quickening inside her by the time she’d been in The Fellowship for a few months. That was when she realized that Jacob was not in love with her—he was in love with everyone—or so he claimed. On reflection, Devon realized that Jacob was incapable of loving anyone but himself. As far as Devon knew, all six children in the family were biologically his and their mothers were all very special to him, all sharing his affection. Devon’s heart was broken and she was suddenly disillusioned. Who would hold her up and comfort her and support her now that she was pregnant? The only people she had were her sisters in the family.

There was Charlotte, who used to act out the children’s stories, making everyone scream with hysterical laughter. Lorna could bake like a demon and throw a softball like a pro. Priscilla, who they called Pilly, was prickly except on days following one of her visits with Jacob and for that the others teased her mercilessly. Reese was the oldest of them at thirty-five and though no one had elected her boss, she took on that role all the time, something for which the others were, by turns, either grateful or petulant enough to reduce her to tears. But Reese played an important role in the family—she was the one to deliver their children; she was a doula and a nurse. Mariah was the youngest, shyest, an innocent twenty years old, and all of them tried to shelter her from Jacob...and failed. And finally there was Laine, who hadn’t been with them long and was the most devilish, making them all laugh at themselves and at their weird family.

They squabbled, giggled, played games, sat up late with ice cream or popcorn and told stories, cried for their lost lives, raved in happy delirium for their happiness, spied on each other, sought each other for comfort.

She missed them so. Even the ones she didn’t like so much.

Mercy had been in no physical danger in the family—it was a family that loved and nurtured the children. The real danger was more subtle—having no independence, no identity, no clear choices; no view of the outside world. And then there were the men whose faces seemed to change regularly, the men who tended and moved the marijuana. The women all knew this wasn’t right, that it wasn’t just medicine, but as long as they were safe and happy they seemed comfortable turning a blind eye to the reality.

And then Jacob began to change. He seemed to move from the morally superior position in his rants to being angry, desperate and paranoid. Now that she’d read the online accounts of the investigation, it seemed obvious—he must have changed as the feds encroached and threatened his authority, turning him into a frantic and anxious man. That’s when the idea of leaving proved to be so much more difficult. He must have been afraid people who left The Fellowship would sell him out. Devon had actually thought about leaving for a long time. The minute her baby was born, Devon thought about leaving, trying to think of what she’d do, how she’d manage, because she didn’t want Mercy growing up in that compound in a pair of soft denim overalls and a long braid. But she didn’t want her to grow up hungry and afraid, either.

And now here she was, back at the beginning, living with a grandparent-type figure taking care of her in a comfortable old house in an old neighborhood.

She poured herself a cup of coffee in Rawley’s kitchen. Rawley and Mercy sat at the kitchen table together, coloring on large sheets of paper he’d brought home.

“What is it?” Mercy asked, pointing to Rawley’s drawing.

“You don’t know what that is? That’s a boat! I have to take you to town pretty soon, to the marina and show you the boats. Those fishermen catch all the fish and crab we eat.”

“How do they catch dem?”

“One of these days I’ll show you,” he told her. “And what’s that?” he asked, pointing to a scribbled picture.

“You,” she said. And then she giggled.

He studied the picture closely. Then he made a whole bunch of dots on the bottom of the drawing.

“What’s that?” Mercy asked.

“Whiskers,” he said, and then he grinned at her.

Rawley looked up at Devon. “Remember Cooper’s girl? Sarah? You met her that first morning.”

“Yes, sure.”

“She asked about you, asked if you was still around. I told her you liked it here, that you were talking about looking for work. She said you should come to the new doctor’s open house this weekend—everyone will be there. You can visit a little bit, ask around if anyone is hiring or looking for help. And you can get a feel for if anyone seems to recognize you—you’re going to have to step out of hiding if you really do want work.”

“I know,” she said. “And that’s why I left The Fellowship—I wanted to live in the world again. I wanted to read everything, hear everything, see everything. I know the world is hard and scary, I know. But, Rawley, prison is scary, too—even if it’s a fine, bountiful prison. I was a teaching assistant in an elementary school for a year—the teacher asked the eight-year-olds, ‘Would you rather be on a deserted island alone or with someone you hate?’ And one little boy answered, ‘With someone I hate so I’d have something to eat.’ We laughed so hard. But that’s what a pure, controlled, perfectly constructed and protected commune can be like. Everything is thought through, down to every chore, every meal, the schedules down to the minute, even what we wore so there’d be no competing or envy. Everything except what people feel. It’s a deserted island stocked with your favorite foods, cozy shelters, protection and comfort. And the inhabitants eventually eat each other.”

Rawley just stared at her for a long moment while Mercy scribbled on her page. Finally he said, “I gotta ask. If someone recognizes you, are you in danger?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know for sure. Sometimes people left and it wasn’t given any notice, like everyone just looked the other way. Sometimes they left for good, but others would stay away for a few days and then return. I didn’t leave with permission. I was told I could not take my daughter away. But she’s my daughter.”

Rawley thought about this for a moment, then he said, “Hmm. So, you want to try the doc’s open house on Saturday?”

Again the shrug. “I have to do something. Right?”

“Devon, if you need to get farther away, like way far away, I’ll scrape up some money for a bus ticket.”

“I’m not sure what I should do. But I ask myself—why would they look for me here? Why would they look for me at all? They’re very busy—there are the gardens just starting to yield summer produce, there’s stock, there are children to tend. And they don’t like spending time on the outside. Jacob believes he’s being spied on by the government and by law enforcement, because they want his money and his property. I don’t know how true it is but that doesn’t matter—it’s what he thinks.”

“Jacob?” Rawley repeated.

“The founder. The leader of The Fellowship.” And then she gazed briefly toward Mercy.

Rawley seemed to understand at once. “Ah,” he said. “Well, you look different, Devon. You don’t stand out so much. You can be my second cousin, twice removed, takin’ refuge from a bad relationship, looking for work.”

“Think that would work?” she asked.

“I ain’t gonna kid you, chickadee—if someone from that camp of yours wanders into town and looks you square in the face, they’ll know you. But if one of ’em comes into town lookin’ for a blue-eyed blonde with a long ponytail, Thunder Point folks will say they don’t know any such person. But, you could always scream if you have to.”