По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

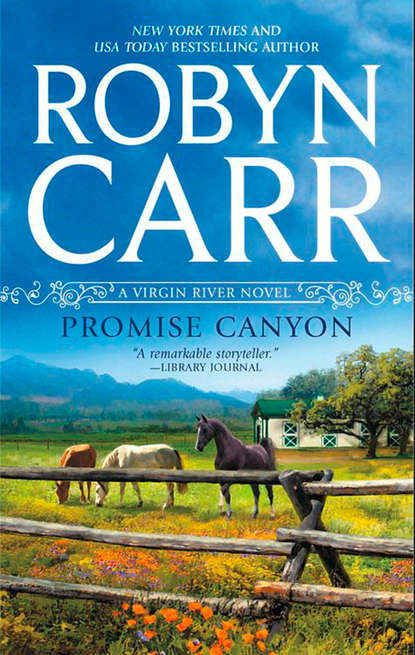

Promise Canyon

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Clay ignored her dismissal, but he smiled at the sight of her hefting that heavy bale and marching into the stable. She was wearing a denim jacket and he would bet that underneath it she had some shoulders and guns on her that other women would kill for. And that tight round butt in a pair of jeans was pretty sweet, too. But the kid didn’t make five and a half feet even in her cowboy boots. Tiny. Firm. Young.

He grabbed two bales and followed her into the stable. She actually jumped in surprise when she turned around and found him standing there behind her with a fifty-pound bale in each hand. She seemed to struggle for words for a second and finally settled on, “Thanks, but I can handle it just fine.”

“Me, too,” he said. “You do the feed delivery all the time?”

“Mondays and Thursdays,” she said, lowering her gaze and quickly walking around him, back to the truck. She reached in after another bale, leaving only a couple of feed bags in the back.

He followed her. “Do you have a name?” he bluntly asked.

“Lilly,” she said, pulling that bale toward her out of the truck bed. “Yazhi,” she added with a grunt.

“You’re Hopi?” he asked. His eyebrows rose. “A blue-eyed Hopi?”

She hesitated before answering. You had to have blue-eyed DNA on both sides to get more blue eyes. Lilly’s father was unknown to her, but she’d always been told her mother had always believed herself to be one hundred percent Native. “About half, yes,” she finally said, hefting the bale. “Where are you from?”

“Flagstaff,” he answered.

“Navajo?” she asked.

He smiled lazily. “Yes, ma’am.”

“We’re historic enemies.”

He smiled enthusiastically. “I’ve gotten over it,” he said. “You still mad?”

She rolled her eyes and turned away, carrying her bale. Little Indian girl didn’t want to play. Once again he couldn’t help but notice the strain in her shoulders, the firm muscles under those jeans. “I don’t pay attention to all that stuff,” she said as she went into the barn.

Clay chuckled. He grabbed the last two bags of feed, stacked one on top of the other and threw them up on a shoulder, following her. When he caught up with her he asked, “Where do you want the feed?”

“Feed room, with the hay. When did you start here?”

“Actually, today. Have you been delivering feed long?”

“Part-time, a few years. I do it for my grandfather. He owns the feed business. He’s an old Hopi man and doesn’t like his business out of the family. Trouble is, there’s not that much family.”

Clay understood all of that, the thing about her people and family. First off, most people preferred their tribal designation when referred to, and family was everything; they were slow to trust anyone outside the race, the tribe, the family.

“Couple of old grandfathers in my family, also,” he said by way of understanding. “You’re good to help him.”

“If I didn’t, I’d never hear the end of it.”

He began to notice pleasant things about her face. She wore her hair in a sleek, modern cut, short in the back and longer along her jaw. Her brows were beautifully shaped. Her blue eyes sparkled and her lips were glossy. She wasn’t wearing makeup and her skin looked like tan butter. Soft and tender. She was beautiful. He guessed she was in her early twenties at most.

“And when you’re not delivering feed on Tuesdays and Fridays?” he asked. “What do you do then?”

“Mondays and Thursdays,” she corrected. “Pay attention. I work in the feed store.”

“Bagging feed?” he asked, his eyebrows lifted curiously.

She put her hands on her hips. “I do the books. Accounts payable and receivable.”

“Ah. Married?”

“Listen—”

“Lilly! How’s it going?” Nate yelled out, approaching from the house, followed by three trotting border collies. “I didn’t hear you pull up. I see you met Clay, my new assistant.”

“Assistant?” she asked.

“Tech, farrier, jack of all horse trades,” Nate clarified. “While we’re getting business up, Clay can function in a lot of roles.”

“Has Virginia actually cleared out? Gone?” Lilly asked.

“Once Clay was en route, she made good on her threats and retired. She’s spending more time with her husband and the grandkids. I’ll be adding too many new requirements to the equine operation and she really wasn’t up for that. I’ve known Clay for a long time. He has a good reputation in the horse industry. We worked together years ago in Los Angeles County.”

“I just saw her a few days ago. I didn’t realize she was that close to her last day. Actually, I thought it would be months,” Lilly said.

“So did we, Virginia and I. But I was lucky enough to get Clay up here from L.A. in a matter of days. As soon as he said yes to the job, Virginia said, ‘Thank God,’ and headed for home. She offered to come back to help or do some job training if Clay needed it, but she’s ready for a little time on her own. She’s been talking retirement for at least a couple of years now but until I found Annie, she wouldn’t leave me alone on the property. She thought I’d mess up the practice.” Nate shook his head in silent laughter.

“You’ll miss her,” Lilly said.

“I know where to find her if I miss her, and so do you! Drop in on her sometime. She promises regular cookies for the clinic.”

“I’ll do that. I’ll make it a point. Let me get your vitamin supplements,” she said, turning to pull a very large plastic jar out of the truck bed. She handed it off to Nate and then fetched her clipboard from the cab so he could sign off on the feed.

“I’m taking delivery on a horse in a couple of days, Lilly. An Arabian. He’s coming for boarding and training, though I think the owner is going to need more training than the horse. Increase the feed for my next order, please. And tell your grandfather I said hello.”

“Absolutely. See you later,” she said, jumping in her truck to head out.

When the truck had cleared the drive, Clay asked, “Is she always in and out of here that fast?”

“She’s pretty efficient. She’s always on schedule. Her grandpa Yaz counts on her. I don’t know if there’s other family. As far as I know, Lilly is the only other Yahzi who works in the business.”

“There’s a new horse coming?” Clay asked. “What’s that about?”

“Last-minute deal,” Nathaniel said. “A woman who doesn’t know much about horses but has an unfortunate excess of money bought herself an expensive Arabian from a good line, learned about enough to keep him alive but can’t get near him. Her stable hand can barely get a halter on him and saddling him is out of the question. If they can get him in the trailer, the hand is going to bring him over here to board so we can work with him. The owner wants to ride him, but if that doesn’t work out she’s thinking of selling him to replace him with a gentler horse. She thinks the horse is defective.”

Clay lifted a brow. “Gelding?”

“Oh, no,” Nate said with a laugh. “Two-year-old stud colt from the national champion Magnum Psyche bloodlines. I had a look at him—he’d be too much horse for a lot of people.”

“She bought herself a young stallion? “ Clay asked, then whistled.

Nate slapped a hand on Clay’s shoulder. “Did I mention I’m glad you’re here?”

“I haven’t unpacked and you have a special project for me,” he said, trying to disguise his pleasure.

Nathaniel grinned. “You don’t fool me. You were a little afraid of being bored and now you’re relieved that there’s a difficult horse coming. It’s written all over your face. Come on—Annie made pot roast. You’ll think you’ve died and gone to heaven.”