По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

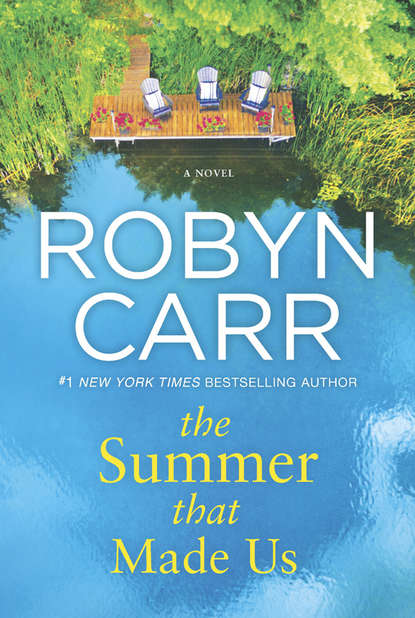

The Summer That Made Us

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#u2940e0eb-3de3-5bdf-bcfb-b9ba8176355d)

Charlene Berkey was devastated. Her television career had come to an abrupt end. She should have been better prepared—the ratings had been falling and daytime talk shows were shrinking in popularity, but she thought her show would survive. The suits at the network kept telling her she’d be fine. Then, without warning, they canceled the show. They didn’t offer her any options. There wasn’t even a position available doing the weather. She was on the street, unemployed and feeling too old to compete at the age of forty-four.

The situation put a terrible strain on her relationship. Michael, typically such a sensitive man, didn’t seem to understand what this turn of events did to her self-esteem, her self-image. She felt overwhelmed, terrified and useless. She had no idea what the future held for her.

If all that wasn’t bad enough, her sister Megan was only forty-two and fighting stage-four breast cancer. Her most recent procedure to beat the monster was a bone marrow transplant and now all she could do was wait.

Charley made a quick decision. She wanted to use this time she suddenly had to be with her sister. She picked up her phone.

* * *

“I want to go to the lake house,” Meg said. “Like we used to when we were kids. I want to get up on one of those bright summer mornings, sit on the dock and watch the sun rise and the fish jump, and see those old fishermen floating out there with their lines cast, waiting for a catch. I want to spend the summer thinking about the way we were—six little blondes with bodies brown as berries. Half-naked, dirty as dogs, flushed and happy and healthy and strong. Our sleeping bags out on the porch, giggling late into the muggy summer nights.”

“While the mosquitoes ate us alive,” Charley said.

“I don’t remember being upset about mosquitoes as a kid.”

“You got it the worst,” Charley said. “You looked like you had chicken pox.”

“I want to spend the summer at the lake.”

“God, no! It’s not the place you remember,” Charley said. “It must be uninhabitable. It’s been years since the family abandoned it. It’s old, Meg. Old and neglected. It’s dying a slow death, I think.”

“That makes two of us,” she said.

“Please don’t say that,” Charley begged.

“John and I snuck up there once,” Meg said, speaking of her husband, a pediatrician to whom she’d been married for twelve years. They were like the perfect couple with the exception of a brief separation just a couple of years ago. “It looked kind of tired and it needs some work. But...oh, Charley, it brought back such wonderful memories. The house might’ve gone to hell like the rest of the family, but the lake is still so pretty, so peaceful.”

“It’s a long way from your doctor, from the hospital,” Charley said.

“Better still. I’m sick of both. I want to rest, have some peace.”

“And you think opening up that lake house against Mother’s express wishes will bring peace?” Charley asked.

“Guess what? I don’t give a shit, how’s that? Bunny died twenty-seven years ago. If Mother wants to suffer for the rest of her life, what can I do about it? It’s time Louise learned, not everything is about her.”

“She’s going to be impossible,” Charley said.

Megan laughed. “Do you care?”

“I don’t have a key,” Charley said, refusing to answer the question. “Do you?”

“You don’t need a key, Charley. Those windows on the porch aren’t even locked. Or the locks rotted away and are useless. We can get in and have the locks replaced.”

“She’ll have us arrested.”

“Her dying daughter? And her unemployed and homeless daughter?”

“You’re not dying! And I’m not exactly homeless—I’m just going to rent out my house so I can come and be with you.”

“You are unemployed...”

“That’s just for now,” she said. “I’m going to be with you until you turn a corner and start to get better. Stronger. Which you will.”

“At the lake,” Megan said.

“Aw, jeez...”

“Admit it, you’re dying to go back. To the scene of the crime, so to speak. We might figure out a few things...”

“What’s there to figure out?” Charlene asked. “It was the perfect storm. Bunny drowned, I was already in trouble even if I didn’t know it, Uncle Roy was down to his hundredth second chance and blew town and Mother and Aunt Jo weren’t speaking. When they couldn’t help each other through the darkness the rest of the family went down like dominoes.”

“All precipitated by Bunny’s accident?” Meg sounded doubtful. “There was other stuff going on or else Mother would have accepted whatever comfort Aunt Jo could give. They were so close!”

“Jo didn’t have much to give just then,” Charley said. “Her husband ran off, leaving her penniless and heartbroken. Mother seemed to blame Aunt Jo. Mother has always found a handy person to blame. All of us kids struggled as a result but I’ve made my peace with it—we were a completely dysfunctional family that, God forbid, should get help.”

Charley had often wondered how they could have been saved from such utter disaster. It was obvious what went wrong—poor little Bunny, gone. But it remained a mystery how everything could go as wrong as it had. That was probably why she had been so successful in the talk show business—that search for answers. She’d had a San Francisco–based television talk show for a dozen years and, since she’d studied journalism and psychology, she’d favored guests who had insights into dysfunctional people and relationships. It had been a very popular show.

And it was now canceled. “I want to go back,” Meg said. “I want to see if I remember.”

There it is, Charley thought. Everyone in the family had their own response to Bunny’s sudden death and Megan’s was to forget. Most of that last summer at the lake didn’t happen in her mind. She had been only fifteen at the time. The doctor called it a nervous breakdown and completely understandable, given the circumstances. They hospitalized and medicated her. She didn’t stay in the hospital long, then came home and seemed her old self with one exception—she couldn’t remember almost a year of her life. Pieces came back over time but it wasn’t talked about.