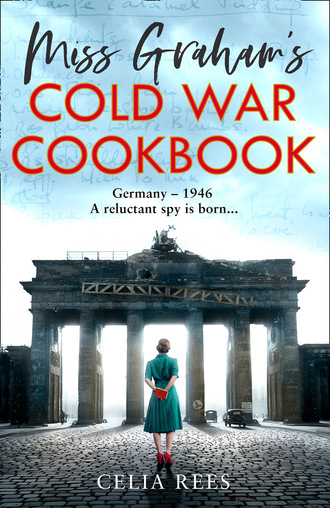

Miss Graham’s Cold War Cookbook

She reached for her briefcase and took out photographs, placing each one on the low table: women in uniform and out of it, some smiling, some serious, some quite beautiful, all of them young.

‘These are girls who were sent to France,’ she said, her fingers aligning the photographs more exactly. ‘Girls whom I sent to France,’ she corrected. ‘And who didn’t come back.’

Four pairs of eyes gazed back at Edith. Four women full of courage and pride who had stepped forward to enter Occupied France, that deadliest of arenas. Four lives given to the service of their country. Four families still waiting for news.

‘Do you think any of them might have survived?’ Edith asked.

‘It is possible. Anything is possible. There’s always hope.’ The black eyes became bleak. ‘But I think it unlikely.’ She paused, seeming to collect herself. ‘We have to find out what happened to our women. Where they were taken, on whose orders, what those orders were, who carried them out. It will be my last service.’ Vera’s fingers lightly played over the young faces. ‘I owe it to their families. I owe it to them.’ Her voice had grown husky. ‘I mean to see them honoured. I’ve made a start but new information is coming in all the time. It’s too big a job for one person. I need help.’ She looked at Dori. ‘A person I can trust and I’ve asked that Dori might join me. We will be working with the War Crimes Commission, tasked with bringing the men responsible to justice, while taking part in a wider search for other criminals of the Nazi regime. Men like your von Stavenow.’

Dori perched on the edge of the sofa. She sat very erect, hands clasped tightly, as if to hold in the tension running through her. She stared at Vera, her face paler than ever, hope and expectation contending with fear of disappointment in her intense, dark gaze.

‘I invited Dori to come today for the yay or nay.’ Vera picked up a silver cigarette case and lighter and lit a cigarette. ‘I’m happy to say it is yay. If it had been otherwise, we would not be meeting.’

Edith didn’t take her eyes off Dori. ‘You didn’t say anything about this.’

‘Dori’s good at keeping secrets.’ Vera drew deeply on her cigarette and let out a stream of smoke. ‘As, I believe, you are, Miss Graham, from what Dori tells me. Hidden depths,’ she gave one of her thin smiles. ‘I like that. I’ve worked with far less promising material, it has to be said. That’s why you are here. Now,’ she tapped ash into a cut-glass ashtray. ‘Leo has asked you to to keep an eye out for Nazi criminals, has he not? Like your friend von Stavenow, or any of his ilk that you might come across. Yes?’ Edith assented. ‘All I’m asking is that you tell us what Leo’s interest is.’

‘Why would you want me to do that?’

‘Because I’m not entirely convinced that it completely coincides with our own.’ She stubbed out her cigarette and sat back, hands folded. ‘Leo belongs to a different branch of the service now. A branch that is not interested in bringing these men to justice. Rather the opposite.’

‘It’s what Adeline was talking about,’ Dori said, urgently. ‘The Paperclip business.’

‘You have proof that Leo, his people, are doing the same thing?’ Edith asked.

Vera nodded. ‘They are calling it Haystack, as in needle in.’

‘And if I find something?’

‘You still tell Leo, or whatever minion he sends, the only difference is, you let us know, too.’

‘So I’d be some kind of double agent?’

‘If you want to put it like that.’

‘Oh, I don’t know …’ Edith said, uncertain.

‘Do you want these men to get away with it?’ Dori gripped her arm hard. ‘Do you? Do you think it’s right when so many died, when they have so much blood on their hands? She stared at the photographs on the table. ‘Look at them. Look! Those are our girls, my friends. It could have been me quite easily.’ She gave a deep sigh. ‘In May, ’44, we had a message. From Paris. It was hard to decipher, but some of it said: They’re sending our joes up the chimney. We took it to mean they were being sent to concentration camps. The Nazis were clearing out Gestapo Headquarters on Avenue Foch, where they took agents. I’ve been there, seen the blood they didn’t bother to clean up, the instruments set out in neat order: scalpels, pliers, hammers and chisels, like a cross between an operating theatre and a carpenter’s bench. It wasn’t just our girls held there and tortured but countless others. Countless! It’s not just the cosh and cock boys we need to go after. That’s what they used, didn’t they?’ Her defiant stare challenged Vera’s wincing disapproval. ‘Rape and torture? They are not so hard to catch. I want the ones who gave the orders. They are the ones who will escape us if we are not careful. So much death, so much suffering.’ Her voice was deep with emotion, her accent pronounced. ‘Then these, these monsters are free to go and live some nice life somewhere, with a new identity as if nothing had happened. Do you want that?’

Edith had never seen Dori so angry, so passionate about anything. Her face was as white as Vera’s, her dark eyes glittering, brimming with tears. She was shaking, gripping so hard that Edith’s arm was hurting. Her carefully cultivated insouciance had slipped. Edith could see now that it was just another disguise.

‘Of course not,’ Edith said, putting a hand on hers to calm her down.

‘Then there is no choice that I can see,’ Dori slowly released her grip, her voice full of unspilled tears.

‘Dori feels strongly about this, Miss Graham, as do I, although I might not use the same language or show my emotions so readily.’

‘I’ll do whatever I can.’

Vera acknowledged Edith’s answer with a slight nod and leaned back in her chair, eyes almost closed. The silence stretched.

‘If messages are to pass between us,’ she said finally, ‘we will need some kind of code.’

‘I can’t just write to Dori, I suppose?’

‘No!’ Both women spoke at once.

‘Your letters will come through Forces Mail,’ Dori said. ‘No knowing who might be reading it.’

‘That someone will is certain.’ Vera’s eyes opened. ‘Germany is under Mil Gov and Lübeck is right on the border with the Soviets.’

‘We need a code and a safe delivery system.’ Dori lit a cigarette. ‘Something simple.’

Vera gave Edith a long, appraising stare. ‘Quite so. Something that sounds innocent but isn’t. Something that only means anything to people who know the code.’

‘A word code would do,’ Dori said.

‘Yes,’ Vera thought for a moment. ‘It would.’

‘A word code?’

‘One of the simplest but surprisingly difficult to crack,’ Dori explained. ‘Messages are sent by card, or letter based on some common interest, bird watching, say, or some other type of hobby. The messages appear to be perfectly innocent but the words are freighted with other pre-agreed meanings which convey a completely different message.’

‘A word means just what I choose it to mean …’ Edith smiled.

‘Exactly.’

Edith frowned. ‘Why all this need for secrecy?’

Dori glanced to Vera, who gave a slight nod.

‘In the war, not just individuals but whole networks were betrayed. Men and women sacrificed …’ She glanced at the photographs spread out on the table. ‘Some of the girls were picked up more or less on arrival, which means the circuit was blown, or there was—’

‘A traitor at the heart of SOE,’ Vera finished. ‘Whoever it was might well have moved on to another branch of the Service. That is why we need secrecy. Such an individual will act without scruple, doing whatever is necessary to save his own skin. What we are asking you to do is not without danger.’

‘We can’t risk—’ Dori started.

‘No, quite,’ Vera interrupted. ‘It has to be secure. Between us. We will give it some thought, Miss Graham. Now, could you excuse us for a little while? We have things to discuss.’

‘Of course,’ Edith got up, taken aback. She hadn’t expected to be dismissed like that.

‘Go for a walk, or something,’ Dori smiled, trying to make up for Vera’s abruptness. ‘We won’t be long.’

Edith turned her collar against the chilling dampness coming up from the river and strode off, hardly knowing where she was going, hands thrust deep into her pockets, while she weighed what was being asked of her. She frowned, burying her chin deeper into her scarf. Dori and Vera were telling her one thing while Leo had told her entirely another. She stopped. Or rather, he hadn’t. In typical Leo fashion, he had outlined Kurt’s crimes, shown her absolute, shocking proof that the man she’d loved had been warped and changed, done the most terrible things, been turned into a monster by the regime he’d served. What Leo had not told her was why he wanted him found. Nothing about Haystack, nothing about finding scientists to use them, nothing like that at all. That had been left to Dori and Vera. They wanted to find men like Kurt to bring them to justice, to make them pay for their crimes. Instantly, instinctively she knew which side to take. She walked on. There was no really choice that she could see. Official Secrets Act, or no Official Secrets Act. No choice at all.

She stopped, mind made up, only to find that she’d totally lost her bearings. She suddenly felt nervous, even panicky, her surroundings unfamiliar, fog coming up from the river. The road was lined with antique shops, most of them closed, windows filled with junk mainly, salvaged from bomb-damaged houses. She hurried to one with lights on and peered through chipped china, dusty pieces of sculpture, jumbled bric-a-brac. The man behind the counter looked up as the bell tinged. He was in his overcoat, his expression flickering between wanting to make a sale and getting to the pub.

‘I’m just about to close,’ he said. ‘Half day.’

‘I just want directions.’

‘Where to?’

‘Lower Sloane Street?’

He gave a wheezing laugh. ‘You’re a bit out of your way. Here.’

He unfolded a worn map of the area, tracing the route with a nicotined finger. As Edith leaned forward, she dislodged a pile of books stacked in front of the counter.

‘How clumsy of me.’ She collected as many as she could, then paused, keeping one back. ‘How much for this?’

The bookseller turned the book in his hands as though it was a valuable first edition even though it was water stained, smelt faintly of smoke from someone’s bombed-out kitchen and he knew perfectly well that it was one of those given free with gas cookers.

‘Depends how much you want it, doesn’t it?’

‘Sixpence?’ Edith ventured. It was worth nothing but she did want it. Badly.

‘Ooh,’ he rubbed the side of his purple, pitted nose. ‘I dunno …’

‘Ninepence?’

‘Done.’

Edith handed him a shilling. He reached for brown paper.

‘No need.’ Edith picked up the book and headed for the door.

‘’Ere! You forgot your change!’

He shrugged and dropped the threepenny bit into the till.

Edith held the book cradled inside her coat. They had one just like it at home: the cover stained, like this, marked with spillages, crustings of flour, pages interleaved with pamphlets (Ministry of Food, Dig for Victory), recipes cut from newspapers, torn from magazines (Meals from the Allotment, Ruth Morgan’s Wartime Cookery, Stella Snelling’s Ideas for Leftovers). They spoke of scarcity, turning the garden over to vegetables, the tyranny of the ration. Besides cuttings, the book held menus collected from restaurants, hotels, RAF messes; recipes written out in Mother’s careful copperplate pencilled on lined paper; Louisa’s purple-inked scrawl on deckled stationery; Edith’s neat, small cursive in washable blue on Basildon Bond. Food, recipes, menus told you an awful lot. Taste and preference defined a person; what was on offer provided a wider context. Messages based on some common interest. Messages that appear to be perfectly innocent … Didn’t this fit that?

They were sitting where she’d left them, enjoying a second round of gin and tonics. The concierge tried to stop her, but she burst in, still in her coat, face pink with the cold and excitement.

‘I’ve got it!’ she said, waving the book.

‘Got what?’ Dori looked up.

‘The code. It came to me when I saw this – the Radiation Cookery Book. A code based on recipes. Everyone is obsessed with food, have you noticed? What’s available, what’s not available: on ration, off ration, blackmarket. Rationing and scarcity only sharpens the appetite. If that’s true here, I can’t see it being different over there.’ Edith paused, the better to order and express the ideas that had begun to seethe. ‘The very words we use can be read in two ways, sometimes more than two. We talk about being in hot water, being hot, or cold, going from the frying pan into the fire, putting things on the back burner and, I don’t know, I’m sure we can think of others. Hot and cold, for example. See here,’ Edith turned to the front of the book. ‘Regulos control the temperature. Regulo 7 is very hot. Things cook quickly. Regulo 1 or 2, cool, slow cooking. I’m sure we can work out a whole code based on this book, understood only by us, each message couched in cookery terms, and Dori has the same edition!’

‘I do?’

‘In your larder. It came with the gas cooker. We use it to agree a code. Anything of interest, I send a recipe or menu, with a note, a card, or letter, message embedded. Every woman interested in cooking swaps recipes,’ Edith added. ‘What could be more natural? Or more innocent?’

‘Or more likely to be beneath the attention of possible censors,’ Dori finished, ‘who are bound to be men.’

Vera leaned back, long fingers laced, her face as severe as ever.

‘It might just work.’ She gave one of her rare smiles. ‘How exactly, will be up to you. Keep it simple. That’s my advice.’

After Vera left, Dori ordered more gin and tonics. Keep it simple. Edith would send recipes to Dori and as a fail-safe to her sister, Louisa. The messages didn’t have to be complicated. They could be limited to certain categories. A person of interest. Contact made. Developments in this area, or that area. Defined by the recipe sent, refined by nationality. British, American, German and anyone else who happens along. What could be more natural than collecting recipes, menus, dishes, from different nationalities?

‘A flavour of the place. A flavour of the people.’

‘Taking the temperature, testing the water?’ Dori ventured.

‘Exactly. With reference to recipes found in here,’ Edith patted the book. ‘Just so you know that such a thing is important.’

‘But I can’t cook,’ Dori said suddenly. ‘Does that matter?’

‘Not at all,’ Edith smiled. ‘It’s even better. I’m teaching you …’

‘Oh, that’s good.’ Dori grinned back. ‘We’ll mark pages up when we get back. Decide on prearranged references. Doesn’t have to be precise. More like progress reports. How you’re getting on, that sort of thing. It’s inspired, Edith. I really like it.’ She finished her drink. ‘More than that, I think it could actually work.’

Back at the flat, they went straight to the basement kitchen. Dori retrieved the Radiation Cookery Book from behind the Bird’s Custard Powder.

‘It’s not much of one,’ Dori sat back when they had finished the code. ‘Rather Heath Robinson, truth be told. It certainly wouldn’t pass muster with SOE, or any other intelligence agency for that matter, but that could be all to the better. Enough for tonight.’

The next few days were spent on the mundane: buying clothes and things that might be difficult to obtain: sanitary towels, toothbrushes, toothpowder, talcum powder, decent soap, makeup, perfume and haberdashery: sewing machine needles and bobbins, ordinary needles and sylko. Useful wampum, Dori called it. Then on Edith’s last evening, Dori came to her room, a fur coat over her arm.

‘I want you to take this. It’ll be cold out there. You wouldn’t believe how cold. Come, try it on.’

Edith slipped her arms into the sleeves. Her hands automatically stroked the thick fur, slippery against her cheek and under her fingers. It smelt faintly of powder and Dori’s perfume, Guerlain L’Heure Bleue, and beneath that, a slight, sharp animal smell.

‘Dori, really, I couldn’t possibly,’ Edith began, although she already felt reluctant to part with the warmth of it, the soft, rich beauty of the fur. ‘You might need it.’

‘What for? I’m not going anywhere. Not yet anyway. It is never so cold here. I have boots. Proper boots. Nice leather, fur lined, knee high. I want you to take those, too. Try them on. We’re about the same size.’

Edith pulled on the boots. They fitted perfectly.

‘This is very generous of you,’ Edith slipped her hand into the pocket. ‘What’s this?’

Her fingers closed around cold, smooth metal.

‘It’s a pistol. The bullets are here.’ Dori held out a cardboard box of shells.

Edith turned the weapon over in her hands. ‘I wouldn’t have the slightest idea how to use it.’

‘I’ll show you.’

‘But is it really … necessary?’

‘Oh, yes.’ Dori said, ‘Vera agrees. We think you should take it for your protection. It could get dangerous.’

Edith had never held a handgun before, let alone used one. She looked down at the dull, dark metal of the short barrel, ran her fingers over the curved trigger inside its guard, felt the hatched rubber of the grip against her palm.

‘But I can’t possibly take it. What if I’m stopped? Searched?’

‘Wrap it in underwear, preferably worn. They don’t like picking through soiled undies. Or in a box of sanitary towels. They never touch those. And you have a rank. Use it. Act innocent but haughty. Haughty gets you a long way.’

‘But I’ve no idea what to do.’

‘I’ll show you.’

Edith listened to Dori’s instructions, watched as her slim, strong, practised hands handled the weapon. She loaded and reloaded the pistol under Dori’s watchful eye, feeding bullets into the clip, taking it out, squeezing the trigger on the empty chamber, noting how the safety mechanism worked, until her hands were grey, filmed with fine-grade gun oil.

‘That should do it. You don’t have to actually shoot a gun,’ Dori said, ‘just know how it works. Aim at the body. It’s a bigger target. Get close enough and even you can’t miss. Once he’s down, move in for the headshot. That way he won’t get up.’

This woman had seen death and dealt it. Edith looked down at the gun in her hand and hoped she’d never have to act on her advice.

‘That’s enough. Wrap it in your knickers.’ Dori stood back to scrutinize. Edith felt like a knight being armed for his first battle. ‘There’s something else I want you to have.’ Dori unclasped the medallion she wore around her neck and handed it to Edith. ‘It is Our Lady of Częstochowa.’

In Edith’s palm lay a tiny oval icon, executed in jewel-like enamel, encased in gold: a black Madonna, her dark face scored and marked, the Christ child in her thin arms.

‘You can’t give me this!’

‘Take it!’ Dori closed her fingers over the talisman. ‘Your need is greater. She will protect you.’

‘Thank you!’ Edith could feel the tears stinging at her friend’s kindness.

‘Let me fix it.’ Dori reached round Edith’s neck and secured the clasp. She held her close for a moment and whispered, ‘May she keep you safe.’

When Dori released her, there were tears in her eyes, too.

6

Blue Train, Hook of Holland—Hamburg

4th January 1946

Blue Train Picnic

Broodje kroket

Rookwurst (Smoked Sausage)

Mustard

Hard-boiled eggs

Genever

Broodje kroket: Not unlike a rissole, flecked with parsley. Made with leftover meat, minced or chopped, mixed with onion but bound with a béchamel then formed into a fat sausage, crumbed and deep fried. Eaten in a bridge roll with mild Dutch mustard.

More like a rissole than a croquette. Find under Meat (66, 63). Can be baked at Regulo 7 (or 6 depending on the oven) or fried for 9 or 10 minutes (turn after 5).

Hook of Holland station. A blue enamel token gave her a place on the train to Hamburg. The line of carriages stood the length of the platform; at the head of them the huge engine hissed steam. Travel came down to a game of snakes and ladders. Liverpool Street Station to Harwich. Boat to Hook of Holland. Now she was on the train to Hamburg. So far, no snakes.

She stowed her leather Gladstone in the nets and took a window seat, resolutely facing the direction of travel. The window was grimed from the outside but she wiped at it, impatient to get going. The stationary train conjured other platforms on other stations. She felt herself slipping backwards into memories she’d been trying to avoid. The awkward farewells at Coventry. The family assembled to see her off, the parting stilted, still coloured by the row that had blown up when she had announced her intention to go to Germany and work for the Control Commission.

‘Are you out of your mind, Edith? I’ve never heard of anything so ridiculous!’

Her sister, Louisa, led the attack since Mother had taken to her bed.

Louisa was the beauty in the family. Even as a child, her looks had gone beyond prettiness. Rich, auburn hair, large dark eyes in a heart-shaped face. Louisa had been her father’s favourite, everybody’s favourite. Spoilt and headstrong, she’d married young. The war had been a godsend to her, allowing her to leave her life in the suburbs and travel with her handsome RAF husband to bases all over the country. But now all that was over. All the glamour had gone. Now this. Just when she was having to adjust to civvy street, normal life again, Edith was planning to swan off. Not only that, but the responsibility of caring for Mother would naturally fall on Louisa. It wasn’t right. It was against the natural order of things and it had put her into a towering rage. She had her own family. Edith was a spinster: it was her job to look after Mother.

She had invited herself and the rest of the family round for a Sunday teatime conflab. Perfectly turned out, as always, in a striped silk shirt and pearl-grey costume, her lustrous hair scrolled back and caught at the nape in a snood, she strode about the small front parlour, full of righteous indignation, gesturing with her cigarette.

‘What on earth are you thinking of? How could you dream of doing such a thing? What about Mother? How will she cope? You know there’s no help to be had these days …’

Brothers, Ronald and Gordon, fell in with her as they always did, adding their chorus: ‘Lou’s got a point there’, ‘Have you thought it through, old thing?’, ‘Aren’t you a bit long in the tooth?’

‘I’m not that old …’

‘Not far off forty!’ Louisa laughed, sneering and harsh.

The sisters-in-law, Trudy and Vi, joined in, bleating protests, shocked that she should dare to break away, duck her responsibilities as the spinster daughter of her elderly mother. Their real fear was that they’d have to take over care of Mother, do the housework, the washing, the shopping, the gardening, keep the lawn mowed and the hedges trim.

Edith tried to explain that she was not doing this out of spite, or to shirk her responsibilities. She wanted to do something. All through the war, she’d seen others leave to join the forces, do useful work. She’d done nothing. She felt wasted, unfulfilled, as though she’d missed an important experience. Others had risked their lives, done things that meant something, that counted. All she’d done was trudge backwards and forwards to school, call registers, teach the girls, come home, do the garden, dig for victory, manage the ration, cook supper, listen to the wireless with Mother. This was her chance to make a real contribution. All this just earned an exasperated stare from Louisa.

‘Oh, for God’s sake, Edith! What do you take us for?’ Her carefully drawn brows arched higher and her red-lipsticked mouth curled with contempt. ‘I’ve never heard such claptrap.’ Louisa turned away to light another cigarette, cupping her talloned fingers as if she was standing in a gale.