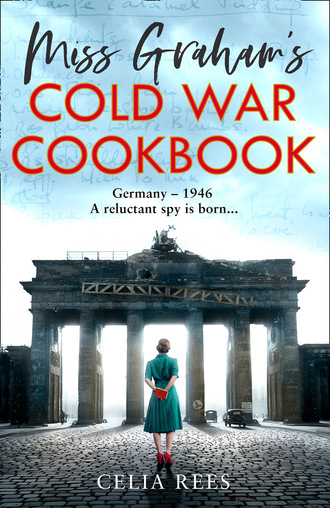

Miss Graham’s Cold War Cookbook

This was true, Edith knew. Dori had spent time in France during the war. It accounted for her mysterious disappearances and Edith had seen the scars on her body and the ones inside that she strove to hide. Once, she’d come back from one of these absences ill and weak, unable to sleep, dark eyes deep and wide with the horrors she had seen. Edith, down in London for the weekend, had come in to find her gaunt and wasted, hunched and shivering with a rattling cough. Edith had not asked where she’d been, what might have happened to account for the state she was in and Dori hadn’t offered to tell her: Careless talk costs lives. She’d just reached out a thin hand and Edith had answered her unspoken need for a friend. She’d stayed to nurse her, cabling Mother that she was caring for a sick friend. She’d sent Anton out to beg bones from the butcher for broth. When Dori was on the mend, the household had pooled their meat coupons and Edith had found paprika to make the goulash that she craved.

It was the Easter holidays. Edith stayed one week, then another. During this time of illness and convalescence, Dori had begun to reveal more about herself. She was from Hungary but had moved to Poland. She’d fallen in love with a British Flying Officer, Robert Stansfield, who was training Polish pilots. They’d left together when war broke out, made their way through the Balkans to Greece, then Alexandria where they were married before coming back to England.

Bobby had been killed in the Battle of Britain. He’d left her this house in Cromwell Square. That’s where the story, as told by Dori, stopped. A few weeks later, Adeline supplied the rest. With Dori, it was personal. The Germans had robbed her of her adopted homeland and the man she loved. She regarded them with a visceral, implacable hatred. She wanted revenge.

‘She wanted to be able to kill ’em,’ Adeline had told her. ‘So she volunteered for a secret outfit who’d let her do just that.’

Now it was all over, but ever since VE Day, Edith had sensed a restive dissatisfaction, almost despair about Dori, as if life was finished and everything to come would be merely a diminishing echo. Edith knew that others felt this too, but no one exhibited this restless ennui as strongly as Dori.

Edith went down the stairs to the bathroom. She could smell the Et Noir bath oil through the door. All the way from Paris. One of Dori’s sidelines. Got to make a penny somehow, darling! It was more than a sideline and Dori was making more than pennies. Not just bath oil. Perfume, makeup, nylons, silk stockings. But it was a risky business and Dori was in deep and getting deeper. Impossible to stop her. She needed the money, but she needed risk even more.

Back in the Bolt Hole, after her bath, Edith opened the drawer reserved for what she thought of as ‘Stella’s things’, unrolling precious silk stockings and laying out silk underwear. Silk, darling, always silk, Dori insisted. Then she flicked through her rail of clothes to find something nice for Leo: the midnight blue silk, long and tight across the hips with a slight flare in the skirt, the shawl collar dipped to expose her décolletage.

Satisfied with her choice, she moved to her small dressing table to do her hair, brushing out the dark-gold waves, smoothing and pinning up the sides, teasing the front section into rolls. She leaned into the mirror to apply her makeup in the way Dori had shown her: eyebrow pencil for definition, the merest hint of rouge. As a final touch, she uncapped a tube of Marcel Rochas lipstick in a silver tube and applied a shade she never wore in her everyday life. She worked her lips together and smiled at her reflection. The final transformation. This was the moment she relished most. She doubted that many of her colleagues at the Headmistress’ New Year’s reception would even recognize her as they sipped Miss Lambert’s sweet sherry and nibbled on sparsely-filled mince pies and meagre sausage rolls.

3

Cromwell Square, Paddington

31st December 1945

Winter Goulash

A good, filling beef stew is always welcome on a night that might be spent at the Warden Post or in the Air Raid Shelter. This delicious continental dish makes a welcome change to more traditional recipes and can be made with the cheapest cuts of meat. It is simplicity itself to prepare: A pound of onions, a pound and a half of stewing steak (shin or the cheapest cut available – skirt will do) and any amount of root vegetables browned well for colour and flavour. A little flour to thicken, a sprig of thyme if you have it; salt, pepper, paprika if possible. Canned or bottled tomatoes, a dash or two of Worcestershire sauce and (my secret ingredient) a dash of Angostura. Enough stock to cover, made up from those kitchen stalwarts the Bovril bottle or the OXO cube. Simmer on a low heat or in a moderate oven (regulo 2 or 3) for two or three hours.

Warming Suppers by Stella Snelling,

Home Monthly, November 1944, No. 36, Vol. 24

In the basement, the goulash was doing nicely, potatoes baking. The canapé plates had come back empty. Time for a drink.

The screen separating the downstairs rooms was opened up. Jazz issued from the gramophone, a tune Edith almost knew picked up and whirled away by a tenor saxophone. A couple were attempting to dance but there was scarcely room to move. Men in chalk-striped suits with thin moustaches, Dori’s new friends, trailed girls with peroxided hair. Poles stood by the door smoking furiously watched by a tall old man with long white hair, sunken blue eyes and a sardonic smile under his yellowing moustache. Anton lived on the first landing and paid no rent. He supplied the paprika. He bowed to Edith, saluting with his ivory-topped cane.

The rooms were stifling, thick with cigarette smoke, perfume and body odour. Edith drifted through enjoying it all.

‘Canapés went down a treat. Come and have a drink. There are impossibly gorgeous men I want you to meet.’ Dori took her over to the drinks table. ‘This is Edith,’ she said to the young man serving. ‘Perfect genius in the kitchen and one of my best friends in the world. Get her a drink, would you, darling? Not the punch. The Poles have tipped a whole bottle of some dreadful hooch into it.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Edith. I’m Harry Hirsch.’ He reached under the table and brought out a bottle of Gordon’s. ‘Will this do?’

‘Very well.’

‘What would you like in it? Not a lot of choice, I’m afraid.’

‘Lemonade’s fine.’

He gave her a wide smile, which Edith returned. Not tall, quite slightly built, but there was a wiriness about him. Good-looking in a delicate sort of way: very pale with thick, black hair falling across his forehead in a boyish cowlick. He was probably older than he seemed at first glance. It showed in the frown marks arrowing down over his nose; the purple smudges like thumbprints beneath his deep-set brown eyes. Edith watched his hands as he poured, his corded wrists, the way the veins snaked over the sliding muscles of his forearms, the skin burnt brown, as if he had spent time in the sun with his sleeves rolled back.

‘Where were you overseas?’ she asked.

‘Oh, Italy,’ he said, ‘Egypt, before that. And Germany. Just back.’ He added a dash of flat lemonade. ‘I could add bitters to jazz it up, but it’s disappeared.’

She took the proffered drink. ‘What’s it like there? Germany, I mean.’

‘It’s a mess.’ He frowned.

‘Really? I’m due out there in a few days.’

‘Are you?’ His eyebrows quirked up, making him look younger. ‘In what capacity?’

‘To take up a post with the Control Commission. You couldn’t tell me a little more, could you? I really don’t know what to expect.’

‘Of course. Happy to.’

He rolled down his sleeves and slipped on a tweed jacket. Moving out from behind the drinks table, he took her elbow lightly and led her to a quieter spot in the throng. His grey flannels had long lost their crease, if they’d ever had one. His white shirt was open at the neck and he wore no tie. Blueish shadow shaded his jaw and upper lip. He had a slightly raffish, bohemian quality that definitely wasn’t British. His English was faultless but spoken with an accent that Edith couldn’t quite place.

‘What will you be doing in Germany?’

‘D’you know?’ She gave a rueful shrug. ‘I’m not quite sure.’

He laughed. ‘You’ll be in good company. Where will you be based?’

‘In Lübeck. Schleswig-Holstein.’

‘That’s a coincidence. I’m going there myself soon.’

‘You’re stationed there?’ Edith asked casually, hoping he’d answer in the affirmative. He really was rather attractive.

‘B.A.O.R. VIII Corps District.’ He gave a mock salute. ‘I’m a captain. Jewish Brigade. We’re conducting interrogations there. I am originally from Latvia, you see, and Northern Germany is full of DPs, displaced persons, from the Baltic countries. We have to sort them out. Sheep from goats. Good from bad.’

‘That must be difficult.’

He grimaced. ‘Almost impossible. But necessary.’

‘Some of the goats are very bad?’

‘Wolves in goats’ clothing, you could say.’ He folded his arms, suddenly serious, his dark eyes shadowed. ‘When are you off?’

‘Fourth of January.’

‘I’m due out a week later. Belgium first, Keil, then Hamburg.’ His face brightened. ‘I say, perhaps we can meet?’

‘Yes, I’d like that,’ Edith smiled, knowing that she really would.

‘Yoo-hoo! Edith!’ Dori was waving from the other side of the room.

‘Over here!’ Edith waved back. She turned to Harry. ‘I have to go.’

‘I meant it about meeting.’ He held onto her hand to prevent her from leaving. ‘CCG Education Branch. Lübeck?’

‘That’s me.’ He really means it! Edith thought with a catch of her breath. Not only that, but she will be in Germany. In that moment, she felt her life turning. This is really happening and it’s happening to me …

‘I’ll find you.’

Edith hoped he would.

‘If I don’t see you before,’ his grip on her hand tightened, ‘Happy New Year!’

His mouth was warm on hers. The kiss lingered a fraction longer than it should have. The intensity surprised them both.

‘Happy New Year.’ Edith didn’t quite know what else to say. ‘Perhaps I’ll see you in Germany?’

‘You certainly will.’ He kissed her hand. ‘I better get back to being barman.’

‘You’re a quick worker, I must say!’ Dori was at her side. She nodded towards Harry Hirsch. ‘What was all that about?’

‘I’m not quite sure,’ Edith replied. ‘I was a bit startled myself.’

‘I rather had my eye on him. But no need to worry. All’s fair and the night is young! Also, Leo’s here. Cab’s outside. Have a lovely evening, darling.’ She dropped her voice and her grip on Edith’s arm tightened. ‘Tomorrow, we need to talk.’

‘What about?’

‘Not here,’ Dori breathed in her ear. ‘Not now. New guests are arriving.’

Edith turned and nearly collided with a tall, elegant woman in a long black gown and a fur stole. She was with a curly-haired young man in evening dress.

‘Oh, I am sorry. I do apologize.’

‘That’s quite all right. No harm done.’ Vera Atkins peered closer. ‘Miss Graham? I hardly recognized you. What a transformation. Going on somewhere?’

Her eyes turned to Leo as he came through the door, shaking moisture from his hat.

‘Bloody weather! Fog’s turning to horrid drizzle. Edith? Are you ready? I’ve a cab waiting.’ He glanced at the woman by Edith’s side. ‘Vera. And Drummond. Well, well. Everyone knows everyone, hm?’

The two men shook hands.

‘Leo. How unexpected.’ Vera Atkins looked from him to Edith, her dark eyes sparking amusement. ‘How do you two know each other? Remind me.’

‘Sort of cousins. Ready, Edith?’

Leo didn’t elaborate further. Neither did Edith. Childhood friends, cousins at several removes. Sometime lovers. As children, they had been co-conspirators, although Edith had learnt to be a wary one. Leo ultimately owed allegiance to no one and there was a streak of cruelty in him. He’d had a knack of drawing her into trouble. She had a feeling he was about to do so again.

4

Savoy Grill, London

31st December 1945

Menu

Consommé

Steak Diane

Noisettes d’Agneau, Pommes Duchesses,

Carottes Juliennes

Glacés

Tergoule de Normandie

One for Louisa!

‘The steak, I think,’ Leo announced. ‘How about you?’

‘The lamb.’

Leo nodded, engrossed in the wine menu. ‘A Reisling, since you’re going to Germany. Then a Duhart-Milon Rothschild, ’34.’ He snapped the menu shut. ‘Had it the other night. Not bad.’

The Savoy Grill was crowded. Leo acknowledged people on nearby tables. There were people here whose fame gave their faces a vague familiarity. Edith tried not to stare. Leo would introduce her as his cousin, if he introduced her at all.

‘Thin stuff,’ Leo announced after two spoonfuls of consommé. ‘I prefer a proper soup.’

‘I was just thinking how different it was from soup,’ Edith looked up. ‘As different as the names. Soup sounds opaque. Thick.’

‘Hmm. That’s how I like it.’

‘What’s this about, Leo?’ Edith said as she finished her consommé.

Leo put up his hand to silence her as a waiter arrived to clear the table and another approached with a trolley.

‘Ah, the Diane! Best way to eat it. You can see what the buggers are doing.’

Leo sat back to enjoy the drama as the deft young waiter fried the steak in butter, executing the flaming with the flourish of a stage magician before transferring the dish to the plate and completing the sauce with efficiency.

‘How is it?’ Edith asked, once they had been served.

‘Not too bad.’ Leo chewed. ‘Better than the one I had at the Club last week – you could have soled shoes with that. How’s the lamb?’

‘Fine.’

It was still pink. At home, the sight of blood brought on universal shudders.

Leo reloaded his fork. ‘Mash a bit fancy for my liking. Club does it better.’

Edith took a forkful of the duchesse potatoes, smooth and rich under a thin golden crust. Trust Leo to prefer lumps. Enough prevarication.

‘So, are you going to tell me?’

‘Not here!’ Leo looked to the nearby tables. ‘You never know who’s about. Let’s just enjoy this, shall we? It’s a bad business.’ He added, sweeping slivers of carrot aside, he was never one for vegetables. ‘Not something to talk about while one’s eating. It’s all in the file back at the flat.’

By the time they got to the flat, Leo had other things on his mind. His attentions started in the cab and their lovemaking was quick with the ease of long familiarity. They had been lovers, off and on, since fumbling adolescence. They were comfortable with each other and the arrangement suited both of them. Edith enjoyed her escapes to London and Leo liked the diversion. He had his life nicely organized in compartments: Sybil in the country, the boys at boarding school, flat in Marylebone for his week in London, mistress up in Hampstead and Edith when she was in town. Edith knew Sybil, of course. They met at family occasions, weddings and funerals, which diverted Leo even more.

Edith left him snoring, wrapped herself in his dressing gown, poured herself a glass of champagne, then turned on the desk light and opened the file marked ‘Kurt von Stavenow’.

She held the photograph of Kurt in a cricket sweater close to her eyes so that she could study it with an intensity that had been impossible before. She’d gone to Oxford on the train to visit Leo. Kurt had been in the Parks watching cricket. Leo took a photograph. The snap was in black and white but Edith’s memory was in vivid colour: blue sky, green grass, the cream of the sweater, Kurt’s hair shining a soft, deep yellow like old gold. When he turned and smiled, the world seemed to stop and start again. Edith couldn’t quite look at him; it was like staring into the sun.

He had begun studying Anthropology at Heidelberg University, he told her in his careful English, but had changed his course of study to Medicine. ‘I want to find ways to bring the two disciplines together,’ he said, interlacing his fingers. ‘To help people, you know? Make them better.’ He’d smiled again. Perfect teeth and dimples. Edith had never thought that a man could be so beautiful. She was scarcely listening as he went on to explain that he was in Oxford to perfect his English and to study his other love, Anglo-Saxon. He talked excitedly about Old English, Norse myths and his new obsession: Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

‘He wants to find the Holy Grail!’ Leo roared with laughter.

Kurt’s brows furrowed, his answering smile uncertain, as if he couldn’t see the joke.

That was the moment Edith fell in love with him.

‘Leo has promised to show me the important places,’ he said, looking down at her. The focus of his attention melted whatever was left inside her. ‘Perhaps if you are also interested, you might like to come along.’

That’s how it started. In the long vacation, Kurt stayed with Leo at Gorton, Leo’s family home. Edith often stayed overnight. Their excursions demanded an early start. They visited the Rollright Stones, Wayland’s Smithy, the White Horse at Uffington, then further afield to Stonehenge, Avebury, Templar churches in the Marches. Kurt took these expeditions very seriously, delving into his haversack for binoculars, maps, ruler and compass to work out alignments, notebook and camera for sketches and photographs. Leo took less of an interest, installing himself at a local pub, leaving Kurt and Edith to explore by themselves.

They would return to Gorton for supper. The house was enchanting, Kurt announced. Ein nette kleine Haus. The remark stung with Leo. He didn’t think it at all small, although Gorton had gardens rather than grounds; it was large, but not remotely stately; looked old but was relatively new. Leo was annoyed, as if he’d been found out in some way. Kurt belonged to a fearfully aristocratic and ancient Prussian family and talked of house parties and hunting parties in great castles. Leo became increasingly huffy. Kurt wasn’t aware of it, but his remarks struck at deeper insecurities: Leo’s father was a Brummy, a generation away from the bacon counter. Leo had begun to move in circles where such things mattered.

‘I’m letting him have the run of the place,’ he’d muttered to Edith, ‘taking him all over the country and the little blighter insults me! Boasting about his bloody schlosses.’

One particular evening, things got so tense that even Kurt noticed. Later, he came to Edith’s room and sat on her bed. It was a hot night and his pyjama top was open. The moon was full, cutting through gaps in the curtains, casting bars of silver over the smooth skin of his bare chest.

‘I upset Leo in some way,’ he said, frowning. ‘This evening, he was off hand with me. That is the right phrase?’ He looked up for confirmation. Edith nodded. ‘I don’t know why he is angry.’

Edith tried to explain. She didn’t think any slight had been intended, but she feared that he, Kurt, might have given the impression that Leo’s house, the way of life here didn’t quite, well, measure up.

‘Nothing could be further from my thought!’ Kurt looked stricken. ‘It is my English. I only say these things because I’m proud to be Prussian. I would love so much for you to come and visit me there. My two best friends.’ He drew closer, taking her hands in his. ‘You believe me, don’t you?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘I thought he was cross with me because of you.’

‘Because of me?’

‘Yes. I thought you and he were, you know, and I’d come between you.’

‘Oh, no!’ Edith had to stop herself from laughing. ‘We were, have been, but …’

She let her words peter out. It was difficult to explain. They’d been very young. It had all been Leo’s idea and she hadn’t liked it very much. Since Leo had gone up to Oxford, he’d been less attentive, pursuing something else Edith suspected, although didn’t really care to ask.

‘But not now?’

‘Not now,’ Edith confirmed. ‘I think he has,’ she hesitated. ‘Other interests.’

Kurt had nodded. ‘I understand. Many of the fellows in the college are, ah …’ it was his turn to pause, ‘of similar inclination. Is that correct?’

‘Completely.’

‘I’m glad Leo is, too,’ he leaned towards her and they were kissing.

‘Let’s go out.’ He took both her hands in his. ‘Let’s go outside.’

They walked barefoot in the moonlight, across the silvered lawn to the lake which lay as still as mercury. ‘Let’s go in,’ he whispered. They kept on walking, the water soft as silk on the skin. The next night they swam to the island. They made love on an old picnic blanket that Kurt had brought out earlier in the day. He was so very different from Leo …

They tried to be discreet but Leo knew right away. He didn’t seem to mind at all. He was glad to have Kurt off his hands. He’s all yours, old girl.

Kurt came to see her in Coventry on an old motorbike that he’d found in the stables. If Gorton had seemed small, Edith’s house must have been sehr klein indeed, but Kurt seemed to enjoy his visits. He’d spend ages working on the bike with her brothers, Ron and Gordon. They were mad about engines. ‘I like your father and brothers,’ he told her. ‘They are workers.’ He held up his hands. ‘They make things.’ He liked talking to them about cars and the motor industry. In a city famous for car manufacture, the boys had followed their father into the works. Gordon to the Standard and then to Whitley. Ron had an engineering apprenticeship with a firm in Rugby making turbines. They were proud of what they did. Keen to show Kurt. He followed with his haversack, making notes, taking photographs, as interested in the factories as he had been in Avebury.

Now she knew why.

There were maps in his file. Coventry and surrounding towns, the factories marked for the Luftwaffe. The Lockheed in Leamington Spa, BTH in Rugby. Her family had liked Kurt, made him welcome. He had a way with him: flirting with Louisa, complimenting her mother on her cooking. He knew how to get along with men and how to please women. They had been kind to him yet her father, her brothers could have been in those factories when the bombs rained down.

How naïve she’d been. How impossibly stupid. It was all here.

von Stavenow, Kurt Wolfgang

1931 – Joined National Socialist German Workers’ Party

1937 – University of Heidelberg – Doctor of Medicine

1936 – Member of the Schutzstaffel (SS)

1937 – SS Ahnenerbe (and a helpful addition in pencil: pseudo-scientific institute founded by Himmler to research the archaeological and cultural history of the Aryan Race)

Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS (Ausland-SD) (another addition: Foreign Intelligence – see over)

It had been lies from start to finish. For each action, an equal and opposite motivation: Principia Mathematica of the human heart. The shock of it jarred; old fracture lines started to crack open until she was fighting back tears.

At the end of the summer, Kurt had had to go back to Germany, departing with unexplained suddenness and abundant promises. He would write. She would come to see him. They would walk by the Rhine and the Neckar, hike in the Odenwald. He would recite eddic poems, heroic lays, stories from the Nibelung. They would sleep in little lodges smelling of pine and resin. They would go to the Black Forest and the Harz Mountains, camp on the Brocken, climb to greet the May Day dawn.

Before he left, they agreed she was to go out the following year. She remembered the fierce excitement she’d felt anticipating their meeting. They would be able to spend all the time they wanted together. The rest of their lives.