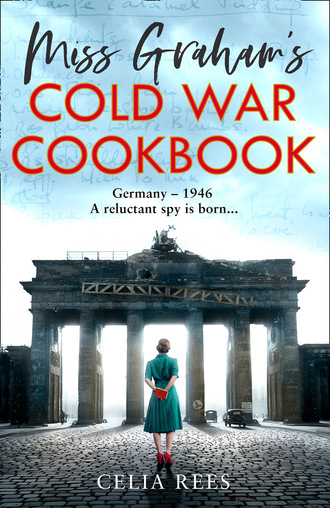

Miss Graham’s Cold War Cookbook

‘You are due to leave for Germany soon to take up a position with the Control Commission, Education Branch,’ the woman read from her file. ‘That is correct?’

She spoke in German now. Edith replied in the same language. The interview was taking a different tack.

‘Before that you were working in a girls’ grammar school, teaching Modern Languages?’

Edith agreed again.

‘For how long?’

Edith answered her questions, going through her education: her degree in German from Bedford College, London. Time spent in Germany, dates and places. Finally returning to her application to join Control Commission, Germany.

‘Why?’ the woman asked.

‘Why what?’

‘Why did you apply? It’s a simple question, Miss Graham.’

‘Those are often the hardest to answer,’ she said. Her smile was not returned. ‘I spent the war at home. This is a chance for me to do something. Make a contribution.’

Even to her own ears, her words sounded trite, banal. How could this woman with her important job, involved in goodness knows what, possibly understand the tedium of life as Senior Mistress in a provincial girls’ grammar, with responsibility for Languages, Ancient and Modern, and the lower school? And when she wasn’t doing that, she was looking after her mother while everyone else, it seemed, was off somewhere doing something. Dangerous, maybe, even deadly, but exciting, even so.

Looking back, that time, wartime, seemed melded into one big mass, like the congealed blobs of metal and glass one found after a raid, impossible to see where one thing begins and another ends. So it was with the succession of days. Even raids had a tedious sameness. The dismal wail of the siren, getting Mother up and down to the shelter, listening for the drone of the bombers with that nerve-shredding mix of dread and boredom that came from not knowing when they would come, how long it would last, when it would be over. Then an hour or two of fitful sleep before the exhausting journey across town to work, on foot or by bicycle, with the plaster and brick dust hanging in the air, depositing a fine film everywhere, rendering pointless Mother’s constant dusting and cleaning. Some nights, she would get Mother settled in the shelter and then return to bed, not caring if she was blown to smithereens, in some ways wishing for it. The only relief had been rare escapes to London and Leo.

‘And how did you find out about the Control Commission?’

‘A colleague. Frank Hitchin.’

‘Who is he?’

‘My opposite number in the Languages Department at the boys’ grammar school.’

‘They’re looking for teachers,’ Frank had told her, ‘German speakers, to go there after it’s all over, help sort out the mess it’s bound to be in. I’m going to give it a go. They’ll probably be taking women, too. Spinsters, you know. No ties and nothing to keep ’em. Fancy free.’ He’d winked. ‘Why don’t you apply?’

Fancy free? If only he knew.

She’d pedalled home that evening, parked her bike in the garage with Mother waiting for the click of the garden gate. Tea on the table. Then cocoa and the six o’clock news on the radio. More V2 bombs in London but the Allies were crossing the Rhine; the Russians had reached the Oder. Surely the war was nearly over? ‘Then we can get back to normal’ her mother had announced with some satisfaction as she turned a row in her knitting. By that she meant, how things were before. To Edith, the prospect of peace felt like a closing trap. The Control Commission offered an escape. For a spinster teacher in her thirties, such opportunities did not come often. She was as well-qualified as Frank Hitchin and she’d spent time in Germany before the war, which was more than he had.

She’d said nothing to the family. They’d only try to stop her.

She’d had a reply almost by return, forms to fill, an interview. Nobody at home had the least idea. She didn’t tell them until it was too late and she’d given in her notice.

‘And what will your job entail?’ her interrogator enquired. ‘Teaching?’

‘The teaching will be done by the Germans,’ Edith replied, referring back to that day’s briefing. ‘We are there as administrators. Inspectors. Our job will be to set up schools where there are none, get them up and running. Vet staff. Get the children in.’

‘I see.’ The woman glanced back at the file. ‘And a high position. Senior Officer, equivalent to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.’ She sat back, fingertips together, assessing. Then she smiled. ‘You speak German very well,’ she said in English. ‘Very fluent with a good accent.’

Edith nodded in acceptance of the compliment. She had a good ear for languages and accents. Something in this woman’s speech said she was not British. There had been a lecturer at college who could have been her brother.

‘I could say the same thing. I’ve been trying to place your accent. Romanian perhaps?’

A lucky guess. The woman coloured slightly. There was a pause. Then she gave a slight nod, as though she had decided something.

‘I would like you to read this and sign.’ She took a form from the top-right desk drawer and pushed it towards Edith.

‘What is it?’ Edith asked, taking it from her.

‘It’s the Official Secrets Act.’

Edith glanced down the page of regulations. ‘What is this all about?’ she asked again.

The woman allowed herself a thin smile. ‘We can go no further until you have signed.’ She offered her pen. ‘Here. And again here, if you would. And your name, clearly printed. Thank you.’ She took the document and slipped it into a file. ‘I am Vera Atkins.’ The name meant nothing to Edith although it was clearly meant to command recognition and respect. ‘From now on, all proceedings are covered by the Act and cannot be repeated, now or at any time in the future. You understand? Perhaps you need more time to consider …’

Edith shook her head, impatient to know what was going on.

‘Now, back to Kurt von Stavenow. Or should I call him Graf von Stavenow. A man of many titles, it seems.’ Miss Atkins pushed his file across the desk towards Edith. ‘Do you recognize him here?’

Edith wanted to think that she didn’t recognize him, didn’t want to recognize him. His extreme good looks were heightened to a sinister glamour by the black SS uniform: the silver epaulettes, the lightning rune on the right collar, and the four silver pips on the left to show his rank. But of course she did. His blond hair looked darker and was dressed differently, combed to the side and cut shorter. His face had filled out, but still retained a certain boyishness; those high cheekbones, that cleft in the wide, square chin. He was not looking straight at the camera but off to the right, a look of resolute aloofness, his deep-set eyes pale under dark sweeping brows.

‘Did you know that he was a high-ranking member of the SS?’ the woman asked with a crimson slash of a smile.

‘No, of course not.’

Edith felt her cheeks grow hot. She was close to losing her temper with the testing, teasing nature of the interview but it wasn’t that which was bringing the blood to her face. Her grip on the photograph tightened, denting the corners. She’d known him. Known him well. They had been lovers. Whatever had happened between them, she’d thought him fundamentally good. She’d often wondered what he might be doing but she could never have imagined this. The glossy paper creased further under her fingers. An officer in the SS? The opposite, if anything. She’d worried he’d get mixed up in something. End up in a concentration camp. She would never have thought this of him. Never have dreamt it. How could he? How could this be? Her stare intensified as though the image might speak to her. She glanced away and back again. Perhaps it was a mistake. Perhaps it wasn’t him. But that was even more foolish. She felt some of her certainty about the world and her place in it shift. It was him all right.

‘When was the last time you were in contact with Sturmbannführer Kurt von Stavenhow?’

‘I didn’t know him as Sturmbannführer von Stavenhow.’

The woman sighed in obvious frustration, but Edith felt she needed to make the point.

‘Very well, when did you last see Kurt von Stavenhow?’

Edith thought for a moment. ‘It would have been 1938.’

‘You don’t seem too sure.’

‘It was 1938. In the summer.’

‘Not since then?’

‘Of course not!’ Edith snapped. ‘We’ve been at war!’

Perhaps he hadn’t done anything terrible, part of her mind continued to reason as she answered questions. Perhaps he had been involved in some form of resistance, a plot against Hitler. Perhaps that was the reason for this current interest. Yet there was something in those slanting black eyes, a slight twisting of the lip that spoke of a deep contempt, even hatred, for anyone who had even been associated with this man, who might ever have called him a friend. Such loathing was not aroused by innocence. What had he done?

‘Ah, here you are!’

The connecting door to the next office opened and there was Leo, coming through in a bustling hurry. Edith had the feeling that he had been there all the time.

‘Sorry I’m late! Meeting ran on and on. How are you two getting along? Like a house on fire, I shouldn’t doubt.’

He rubbed his hands together, choosing to ignore the frigid atmosphere, or failing to notice it.

‘I think we’ve finished.’ Vera capped her pen.

‘Everything satisfactory? Edith pass with flying colours?’

‘Perfectly.’ She stood up. ‘And yes.’

‘In that case, thank you, Vera,’ Leo at his most avuncular. ‘Now, don’t let us keep you. I’m sure you have plenty to do, gathering your bits and pieces and so on.’

Vera looked around the empty room. ‘I’ve already done so. As you can see.’

‘Hmm, yes, well …’ Leo rubbed his hands again. ‘Don’t let us keep you, as I say …’

Vera held Leo’s eyes in her level black stare before slowly fitting her pen into her briefcase. It was unclear who was dismissing whom.

‘Oh, and leave those files on the desk, would you?’ Leo added.

‘I had every intention of doing so,’ Vera said as she put on her coat, ‘since they no longer have anything to do with me.’ Quite unexpectedly, she turned as she moved to the door and proffered her hand to Edith. ‘Auf wiedersehen, Miss Graham.’ Her handshake was firm and strong. ‘You have a formidable task in front of you with the Control Commission. A great responsibility.’ Her grip became more emphatic. ‘May I wish you good luck.’

‘You mustn’t mind our Miss Atkins,’ Leo said as the door closed behind her. ‘She’s got a good eye, old Vera. Good instincts.’ He collected the files from the desk. ‘Particularly good with the girls. None better. If you pass the Vera test, you’re on your way.’

‘On my way to where?’ Edith asked as she followed Leo out into the corridor. She caught his arm, slightly disoriented, still shocked by what she’d heard about Kurt. ‘What am I doing here, Leo? What’s this all about?’

‘When you said you were off to Germany, I had an idea, that’s all. It’s a frightful mess over there. Chaos doesn’t begin to describe it. Our zone is full to bursting, God knows how many from God knows where – the unfortunate residents of the bombed-out cities, demobbed soldiers, ex-slave workers, refugees from all regions east who’ve fled from Uncle Joe’s forces and who can blame them for that?’ He frowned. ‘Among them are some bad hats, some very bad hats, taking advantage of all the chaos and confusion. Hiding in plain sight. Nothing suits them better. Our job, or part of it, is to winkle them out. Simple as that. We need all the help we can get, quite frankly.’ He looked at her, blue eyes magnified by his glasses. ‘Since you’re going there, I thought you might do us a little favour.’

‘Is Kurt one of these bad hats?’

‘Most emphatically, I’m afraid.’

‘But what has he done?’ She held onto his arm, wanting, needing an answer. How could this possibly be? The Kurt she knew transformed into Sturmbannführer von Stavenhow?

Leo glanced round. ‘Not here. I’ll explain later.’

Edith looked down the deserted corridor, the parquet dulled and scored, marked with cigarette burns. The tall windows filmed with grime, still criss-crossed with peeling tape.

‘What is this place, Leo?’

‘It’s a place that’s never existed officially and is about to cease to be entirely.’ He nodded to a pile of boxes stacked by the door.

‘Secret, you mean? Hush-hush?’

He nodded.

‘What am I doing here? What do you want me to do, exactly?’ Edith asked, a sudden, cold realization dawning. ‘Be some kind of spy?’

‘I wouldn’t go as far as that. Not in the accepted sense.’

‘The Official Secrets Act?’

‘Oh,’ Leo waved a dismissive hand. ‘Everyone signs that. People get the wrong end of the stick about intelligence work. Most of it’s done by perfectly unexceptional types: businessmen, travel agents, teachers, clerks, typists, shop assistants, anybody really. Ordinary men – and women. It’s mostly a matter of keeping eyes and ears open, passing on information. Women are excellent at it. Superior intuition.’

Edith frowned. ‘How do you know I’d be suited?’

‘Oh, you’d be perfect.’ He looked at his watch. ‘Better get the old skates on. You’ll find the driver waiting.’ He kissed her on the cheek. ‘I’ll pick you up from Dori’s at eightish. Wear something nice. I’ve booked a table at The Savoy.’

Edith sat in the back of the car. The driver seemed to know where he was going without her instruction. What was this about? She’d done favours for Leo before. Attended meetings at university, dropped off a parcel or two, collected ditto. Sat on a certain park bench until a man walked by with a dog. Another park, another town. Wait by the floral clock. Same man. Different dog. What did Leo want? The Official Secrets Act suggested something serious. In Edith’s experience, the swankier the place, the bigger the favour and it didn’t get swankier than The Savoy on New Year’s Eve.

2

34 Cromwell Square, Paddington

31st December 1945

Ration Book Canapés

Quickly made from readily available ingredients, serve these delicious savouries to your guests with drinks or before dinner. Hand round fried cubes of spam, speared on toothpicks; triangles of thinly cut hot toast, crusts removed, spread with fried corned beef or tinned snoek mashed with pepper and vinegar. Keep the crusts to make breadcrumbs.

Stella Snelling’s A Dozen Delicious Ways with Canap é s

Women’s Journal, week ending 23rd January 1943

Dori’s square was close to Paddington Station. One side was a great yawning cavity, the buildings flanking the gap shored up with beams wedged against the walls. Dori’s row was more or less intact, although some of the houses were boarded, either unsafe or waiting for their owners to return. Dori’s was second from the end, the cream frontage in need of repainting with chunks of stucco missing. All the result of the bomb that had brought Edith here in the first place.

Edith thanked the driver and went down the basement area steps to the kitchen. She didn’t feel ready yet to join the party going on upstairs. Dori’s parties started early and went on late.

Easter time, 1941, she’d stumbled down these very steps with bells clanging, wardens shouting, half the square smoking rubble and the trees on fire. After a weekend in Leo’s flat, she’d been trying to get home when she’d been caught in a raid and been diverted, herded into the shelter of the tube at Paddington. Adeline had been on the platform, taking photographs. An unmistakable figure, her flying jacket hung about with cameras, her white-blonde hair jammed under a soft peaked cap. Edith had first met the American journalist through Leo and they’d hit it off immediately, meeting up when their paths crossed in London. Edith waved, relieved to see a friendly face among so many strangers. Adeline smiled, equally as pleased to see Edith. Adeline shared her small silver flask of bourbon and they’d settled down together to sit out the raid, talking about who they’d seen, where they’d been and everything in between.

After the all clear sounded, they’d emerged to fires raging. Then, guided by some kind of premonition, Adeline had hauled Edith into a deep doorway just as another bomb went off, very near. A delayed fuse, a tail ender dropping the last of his load. The explosion had sucked all the air. They had clung to each other, the vacuum pressing them together like giant hands, while bricks flew, bouncing past like children’s toys. Adeline had taken her by the hand and they’d stumbled through fallen masonry and abandoned cars towards the entrance to the square. A warden shouted: ‘You can’t go no further!’ and Edith had baulked but Adeline had just gripped her hand tighter, pulling her down steps with the warden still yelling.

Half the square were in Dori’s basement. ‘Waifs and strays, orphans from the storm!’ Dori had waved a bottle of gin in greeting. ‘Come and have a drink, darlings. It’s the only thing to do!’

Adeline had gone straight back out. She had to capture what she’d just seen: the destruction of the square, the flames in the trees, the faces of firemen and ambulance crews strained and white in the flashlights’ glare, even the irate ARP warden, would appear on American breakfast tables in the pages of News Illustrated. Edith was just relieved to be out of it, glad of the shelter and enjoying the impromptu party. So much better than being at a freezing station, waiting for the trains to start running; so much more fun than sitting in the air-raid shelter at home.

By the time the trains were running, Dori had taken to Edith: ‘You can cook! Come any time!’ she’d said and meant it. Edith was equally taken with Dori; ebullient and flamboyant, she was fascinatingly different from anyone else Edith knew. She took to dropping in whenever she was in London and needing to find somewhere to stay when she was in the city, she joined the ever-changing group of people who periodically lodged with Dori. It was never for long: a day or two, a weekend here and there, a week at the most, but it became her lifeline.

Edith let herself into the kitchen and found a couple of young things standing by the kitchen table looking bewildered.

‘Is that you, Edith?’ Dori came from upstairs. ‘I thought I saw you sneaking in.’ Her voice was slightly slurred, as though she’d started the party early, but when she appeared in the kitchen doorway, she looked lovely. Her green silk dress cut low, her black hair falling in deep, soft, sloping waves. A light dust of powder gave a hint of colour to her pale, ivory skin; eyebrows defined to accentuate the tilt of eyes made to look even darker and larger by a sweep of liner and liberal use of mascara. ‘Meet Pam and Frankie.’ The two girls bobbed their heads slightly, as though Dori was royalty. ‘You couldn’t help them rustle up some of those delicious canapés, could you, darling?’ She gave Edith her best red lipstick smile. ‘I’ll pop the geyser on and run your bath.’ She disappeared up the stairs again. ‘And check on my goulash!’

The girls turned to her expectantly. FANYs most probably. Dori had lots of friends in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. Whatever their duties might have been, they did not appear to have included catering.

Edith went to the Aga and lifted a lid. ‘Good God! What is this?’

‘The goulash?’ The taller girl volunteered.

Edith inspected the thin stew, feebly bubbling on the Aga. Dori was proud of her national dish, but she was no cook.

‘What do you want us to do?’ The other girl asked plaintively. Edith directed them to the larder to fetch corned beef and spam. She’d prepared something similar that first night to pay back the generosity of her hostess. She’d been surprised and delighted by Dori’s genuine pleasure in her skill at making something from nothing – canapés, a flattering term for titbits on toast.

‘Ooh, Stella Snelling’s canapés.’ The girl smiled. ‘My mum did those at Christmas. She collects all her recipes.’

‘You’ll know what to do, then.’ Edith smiled back.

Edith went to her own shelves in the pantry for OXO cubes, Bovril and her precious bottle of Worcestershire sauce. She raided Dori’s cupboard for the fiercely guarded tin of paprika pepper. A couple of teaspoons more wouldn’t hurt.

‘Go upstairs, would you?’ she asked the tall one. Frankie, was it? ‘See if you can find me Angostura bitters.’ Just a drop works wonders! (Stella Snelling: Tips to Cheer Up Tired Dishes.) Pam was ready with the titbits. ‘Under the grill. Not the Aga. The gas cooker.’

A recent addition to Dori’s kitchen. The Aga had become increasingly temperamental and there was the shortage of fuel.

Pam opened the oven door. ‘There’s a book in here!’

‘Well, take it out! When you’ve done that put some potatoes in to bake.’

Hanging above the Aga were herbs Edith had scavenged from a bombed-out garden. She broke off thyme, sage, rosemary, bay. The scent reminded her of home. She put that out of her mind. Mother would be round at Edith’s sister Louisa’s by now sipping a festive sherry, already getting on her younger daughter’s nerves, complaining about Edith’s imminent departure for Germany. She would not feel guilty. Their problem now.

Edith took the narrow stairs up to the Bolt Hole, the tiny attic room she rented at the top of Dori’s house. It was her refuge. It offered a place to stay on her trips to see Leo or when she needed to escape the suffocation of home. It was paid for by the money she made from her recipes: she’d said nothing to the girl in the kitchen, but she’d been writing cookery tips as Stella Snelling for years now.

The great thing about Stella was that she had been a real person in Edith’s life – a friend from college who then became a fictitious, handy pal in London and holiday companion. The family had met Stella, so they never questioned Edith going to see her in London or their holidays abroad: cover for her trips with Leo. Even though he was family and they’d been in prams together, jaunting off with him would have caused more than a few frowns. Edith discovered that having a phantom female companion freed her, for a while anyway, from the dull routine of work and the constraints of the family.

The real Stella had married and emigrated to New Zealand but Edith conjured her again when she began to submit wartime recipes, in answer to an invitation in Woman’s Journal. Edith enjoyed cooking and liked to think of ways to make the ration go further. There was no dearth of tips. Every woman she knew had their hints and tricks: her mother, sister Louisa, Mother’s friends in the W.I. and the Townswomen’s Guild. The magazine accepted her writing and wanted more. She sent her recipes as Stella Snelling, hiding behind the pseudonym’s anonymity. She didn’t want anyone at home to know and she liked the idea of Stella as much as she disliked the way people made judgements about her based on her job and her unmarried status.

She stripped off Edith’s tweed costume and sensible blouse, balled her lisle stockings and wrapped herself in the burnt-orange shantung robe she’d come to think of as Stella’s. The tips and recipes didn’t interest Dori but she’d immediately loved the idea of Stella, intrigued by this hidden aspect of Edith and happy to help find what Edith increasingly identified as her ‘Stella side’. They had gone shopping for ‘Stella’. Dori knew all sorts of unfortunates ready to sell the most wonderful clothes for next to nothing. Any qualms were firmly squashed with a ‘Nonsense, darling, you’ll be doing them a favour’. Dori had taught her about labels and fashion houses, shown her how to wear her new wardrobe, put on makeup, do her hair. Become a very different version of herself.

Dori seemed to have a talent for this chameleon-like change from one personality to another. Nothing was certain about her: who she was, where she came from, how she had tipped up in London, what she did exactly, even her age was a matter for conjecture. The stories changed depending on who was doing the telling. She was a Hungarian countess who had been married to a Polish cavalry officer who had fallen in the last charge. She had fled the Nazis, pursued on skis across the mountains. No, she was Hungarian all right, but Jewish, and had escaped through the Balkans. No, that was wrong. She was Polish, not Hungarian. She’d married a White Russian and had lived in Paris, got out just before the fall of France. The stories fed on themselves, each one more exotic. The only common thread? Dori was a spy.