По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

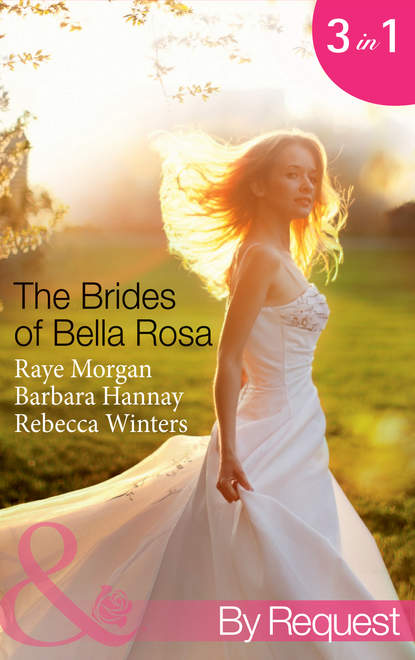

The Brides of Bella Rosa: Beauty and the Reclusive Prince

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Isabella turned bright red and had to pretend to be looking for something in the huge wall refrigerator in order to hide that fact until things cooled.

“What prince?” she chirped, biding her time.

Susa’s laugh sounded more like a cackle. “The one who punched you in the eye,” she said, elbow-deep in flour. “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

Isabella whirled and faced the older woman, wondering why she’d never noticed before how annoying she could be. “No one punched me. I…I fell.”

“Ah.” Susa nodded wisely, a mischievous gleam in her gray eyes. “So he pushed you, did he?”

“No!”

Isabella groaned with exasperation and escaped into the pantry to assemble the ingredients for the basic tomato sauce that was the foundation of all the Casali family cuisine. Let Susa cackle if she felt like it. Isabella wasn’t going to tell her anything at all about what had happened. Pressing her lips together firmly, she set about making the sauce and pretended she didn’t know what the older woman was talking about.

She couldn’t discuss it yet. Not with anyone. She wasn’t even sure herself what exactly had happened. Looking back, it seemed like a dream. When she tried to remember what she’d said or what he’d done, it didn’t seem real. So she washed the clothes the prince’s sister had loaned her, sent them back to the palazzo, and heard nothing in return. She had to put it behind her.

Besides, she had other problems, big problems, to deal with. She’d been putting off thinking about them because she’d assumed she would go to collect the Monta Rosa Basil and all would be well—or at least in abeyance. Without the basil, she was finally facing the fact that the restaurant was in big trouble.

Luca, her father and founder of Rosa, had gone into a panic when she had told him a sketchy version of what had happened and then tentatively speculated what life—and the menu—might be like without the herb.

“What are you talking about?” he demanded, looking a bit wild. A tall, rather elegant-looking man, in Isabella’s eyes, he radiated integrity. Despite the demands he tended to put on her, she loved him to pieces.

“The old prince said I could come any time.”

That was news to Isabella. She’d had no idea there was any sort of permission granted, and she had to wonder if it wasn’t just a convenient memory her father had embellished a bit.

“Well, the new prince says ‘no’.”

“The new prince?” He stared at her. “You’ve talked to him?”

“Yes. A little.”

He frowned. “No, Isabella. Stay away from the royalty. It’s no good to mix with them. They think they can walk all over us and they do it every time.”

“But, Papa, if I’m going to try to get permission to—”

“You don’t need permission.”

She sighed. There was no way she was going to make him understand that the circumstances had changed.

“I’ll go myself,” he muttered. He tried to rise from his chair and she hurried to coax him back down.

“Father, you will not go anywhere,” she said fretfully.

“Don’t you understand how important this is? The Basil is our family’s trademark, our sign of distinction. Without it we are just like all the others, not special at all. It’s who we are, the heart and soul of our cuisine and of our identity. We have to have it.”

She was feeling even worse about this than before. “But, Papa, if I can’t get it any longer…”

He shook his head, unable to understand what the difficulty was. “But you can get it. Of course you can.” His tired blue eyes searched hers. “I’ve never had any trouble. I go in right at sunrise. I go quietly, squeezing through the chink in the wall, right where I’ve entered the grounds since I was a young man. A short hike past the river and up the hill, and there it is, green leaves waving in the breeze, reaching up to kiss the morning sun.” He kissed his fingertips in a salute to the wonderful plants that were the making of his reputation.

Then he frowned at her fiercely. “If you can’t manage to do such a simple thing, I’ll do it myself, even if I have to crawl up that hill. I’ve never failed yet.”

That was it. She was a failure. She sighed. “The dogs never came after you?” she asked him, feeling almost wistful about it.

“The dogs are only out at night.”

“Not anymore,” she said sadly.

She left him pounding his walking stick on the tile floor and grumbling about incompetence, knowing she couldn’t let him attempt the task. The climb up the hill would kill him in his current condition. She had to find a way.

Everyone knew there was a problem. The situation was getting desperate. Her father had let things go too long. They were losing customers and had been bleeding money even before this latest problem. To make matters worse, there was some nonsense about a permit her father had never bothered to get. Fredo Cavelli, an old friend of her father’s and now on the local planning commission, had come by a few times, threatening dire consequences if the paperwork for a permit wasn’t cleared up. The trouble was, she wasn’t sure what Fredo was talking about and her father tended to do nothing but foam at the mouth and accuse Fredo of jealousy and double-dealing instead of taking care of the problem as he should.

It seemed to Isabella that control was slipping away. Without the special ingredient that set their sauce apart, there would be very little reason for anyone to choose their restaurant, Rosa, over the others operating nearby. She was desperate to get a handle on all these problems and get things back on an even keel.

Something had to be done.

She knew what it was. She had to go back there.

Just thinking about it made her shiver. She couldn’t go back. The prince had explicitly ordered her to stay away. And for once in her life, she was not really ready to challenge that.

Odd as it seemed, he was so different, so separate from her way of life, that he threw her off balance in a way no other man had ever done. She was used to being the feisty one, the girl who didn’t accept any nonsense from men, the one who could take it, deal with it, and serve it right back. A handsome face didn’t bowl her over. Charm made her suspicious. The tough-guy act completely turned her off.

Isabella was a hard sell on every level. Life had made her that way. Though she looked happy and carefree to most who knew her casually, there was a thread of dread and unease in her soul that she’d come by naturally.

Her mother had died when she was three years old, leaving her the only female in the family. Her father and her two brothers immediately turned to her for everything. At the age of five she was already taking care of everyone else, in the family home, in the play yard, and even in the restaurant. People in the village called her “little Mama” as she scurried past on one errand or another. She was always in such a hurry to make things right for her little brothers, it seemed she never had time to have a childhood of her own.

But her unease and wistfulness were born of more than just too many responsibilities too early. There were uncertainties in her family background, half-remembered scenes from childhood, secrets and lies. Her mother’s death, her father’s sometimes mysterious background, the reason her baby brother Valentino carried his daredevil act too far, the reason her brother Cristiano felt he had to jump off cliffs to save lives—all these things and more created a shaky foundation for a calm, peaceful life.

Isabella had a recurring nightmare where her family restaurant began to sag, first on one side, then the other. Going outside, she would realize the building had been sitting on a sand dune and the sand was beginning to drain away. Frantically, she tried to shore it up with her hands, pushing the sand back, working faster and faster. But it was no use. The building sank into the sand as though it were water. Inside she could see her father and her brothers trying to get out. She tried to call for help, but she couldn’t make a sound. Helpless, she watched them disappear beneath the surface. And that was when she woke.

“You’ve obviously got a savior complex,” Susa told her the one time she’d confided in the older woman. “Get over it. You can’t save these people. We are each our own worst enemy.”

Susa’s words weren’t very comforting. In fact, they weren’t even very helpful. So she never told anyone about her dreams again. But she thought of them now as she tried to analyze what had happened last night.

As much as the dream unnerved her, misty memories of her night at the castle unsettled her even more. Had he really kissed her forehead or had she just wished so hard that she’d dreamed it? Had she really told him she’d thought he was a vampire for a few shattering seconds? Had she really reached out and stroked his scar as though she had a right to touch him? It didn’t seem credible and it made her blush all over again.

She hadn’t been herself last night. And that was one reason she hesitated to try to go back. What would he cause her to act like if she actually got in to see him again?

Meanwhile she had to deal with losing customers, losing money, and Fredo Cavelli coming by to threaten that he would have Rosa’s closed down for good if her father didn’t come up with some obscure piece of paper.

“He thinks he can order me around because he bribed the mayor to put him on the planning commission,” Luca would scoff whenever she tried to talk to him about it. “I’m in compliance in every way. He can’t run me out of town. He’s just jealous because the little ice cream store he tried to run fell apart in a month. I won’t give in to his rubbish.”

She shook her head and walked away, unsure of how threatening this business really was. She had more problems than she had time for, so she let it go. Meanwhile, several times a day, her gaze wandered toward the hills, searching out the mist-shrouded tower of the castle, just barely visible toward evening, and she wondered what Max was doing in his lonely sanctuary. Was he out riding again? Did he ever think of her? Or had he been so glad to be rid of her, he’d erased her from his mind?

Max was on horseback, surveying the river in the twilight magic that hovered over his land, just after sunset. His sister had gone home, his cousin was about to leave for Milan, and his life was about to get back to normal. Boring, monotonous normal. Still, it was a relief.

This was his favorite time of day, and the only time he found he could come to the river without feeling unbearably sick inside. And he had to come to the river, if only as an homage to Laura. For the first few years after her death, he hadn’t been able to come here without tears flowing freely.

“I’m sorry,” he would cry into the wind, brokenhearted and in agony. “I’m so sorry.”