По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

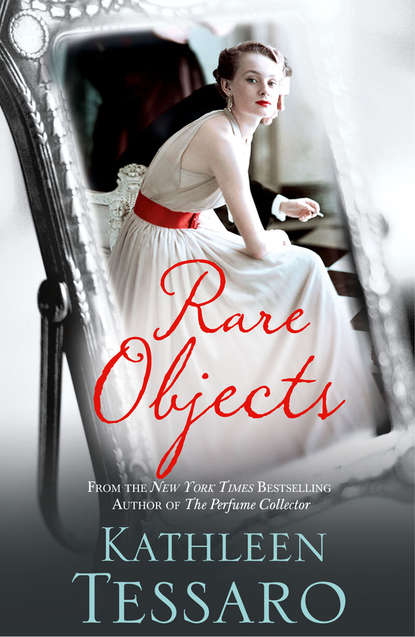

Rare Objects

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I paused.

I was alone in the shop. The ticking of the clocks and Persia’s deep purr were the only sounds.

“Occasionally,” I continued,

I have used your desk for brief periods in order to complete paperwork and I have come to admire the great map on your wall. I am curious as to whether you have been to all those places and what they were like.

Again, I stopped. He might, quite rightly, find the idea of me sitting in his office intrusive. Then again, I reasoned, this letter would most likely rot in the postal box in Baghdad, along with the rest of his mail.

I envy you your freedom, Mr. Winshaw. I wish I too could leave Boston behind. I would like nothing better than to be somewhere new, where people weren’t so bound by convention and narrow-minded ideas of right and wrong, good and evil. I think there’s nothing duller than trying to be good nor any task more thankless. If I were you, I would stay missing as long as I could.

Sincerely,

May Fanning

Well, that was childish.

I tore the sheet off the writing pad and began again.

When I had finished the second letter—a brief, polite inquiry—I looked for envelopes in the drawers of his desk. Failing to find any, I took one from Mr. Kessler and then packaged up the rest of Mr. Winshaw’s mail into a small parcel covered in brown paper and twine and took it to the post office. It took three clerks twenty minutes to figure out the postage to Baghdad. They were naturally curious about who I was corresponding with, what was in the package … I exaggerated a little, explaining it was my husband, the famous explorer, who was abroad and that I needed some urgent signatures on very important business documents.

By the time I left, they were looking at me differently—as if I was fascinating, handling difficult situations on my own, braving the absence of my beloved with dignity and poise. The fantasy lent the afternoon a certain tender hue of melancholy, an imaginary sadness and courage that made everything just a little more interesting.

So I pretended that, in my own way, I’d somehow said “Yes!” to life too.

I was walking past a barbershop in Prince Street when I spotted it, hanging in the window. “Boxing,” the poster advertised in bold red letters across the top, “Five Bouts, Thirty-Six Rounds at Boston Garden.”

I don’t know why I stopped; maybe out of habit, maybe just because things had been going well and I had to test them, poking and prodding at my own happiness the way a child picks at a newly formed scab.

I read through the list of names, searching, looking for the one I wanted to find. And sure enough, there it was, down near the bottom: Mickey Finn.

A sudden wave of loneliness hit me hard. I had my freedom back, a new job, money in my pocket, but still my chest ached the way an empty stomach gnaws and clutches for food that isn’t there.

Michael Thomas Finlay.

For years he’d been as much a part of my life as my right hand.

We’d grown up together, been in the same class for a while in grammar school. But as soon as he’d grown tall enough, in sixth grade, Mick had been pulled out to work on the docks, loading and unloading with his father, brothers, and uncles. Still, I saw him every Sunday at church, sat next to him in confirmation class. When I learned how to waltz, he was my first and only partner.

I must have been staring—there was a rap on the window, and when I looked up the guys in the barbershop were laughing and blowing kisses at me.

I ignored them, walked on. But the emptiness in my chest grew and spread.

I could still remember the first time Mickey kissed me, in the alleyway behind the cinema; the soft, warm pressure of his lips on mine and, most of all, the way he held me—gently, as if I were made of delicate glass he was afraid of breaking. No one before or since had ever thought I was that precious. It was a pure, uncomplicated affection, almost like siblings, based on unquestioning loyalty.

Of course Ma didn’t like him. He was black Irish, she said, with his thick dark hair and brown gypsy eyes. He’d been taken out of school and would never amount to anything.

But I didn’t want anyone Ma approved of.

Then Mickey’s brother started boxing, and Mick took to hanging out at the Casino Club. As luck would have it, he turned out to be even better than his brother; just the right combination of height, muscle, and speed. And there was money to be made, a lot of money, for just one night’s work.

Everyone knew all the best boxers were Irish. Kids from nowhere could rise to the top of the boxing world in no time—going from brawling in basements and back lots to Madison Square Garden in a matter of months. We watched their breakneck rise to stardom on the newsreels every week—Tommy Loughran, Mike McTigue, Gene Tunney, and Jack Dempsey. Punching their way out of tenements straight into movie careers and Park Avenue addresses.

The first time I went to a fight, I was terrified. But Mickey won that night, and my fear became excitement. Soon I looked forward to the sweaty, raw nerves that snapped like electricity moments before the bell sounded; to the fighters, dancing in their corners, skin glistening, muscles tense. All the chaos, the smells, the din of the crowd, the rickety wooden chairs, the hot roasted peanuts and calls of the ticket touts; gangsters smelling of French cologne sitting cheek by jowl with old-money millionaires; the blood, the fear, the speed, the unholy fury of it all, I came to relish every bit. And Mickey, at the center, fighting, conquering the world.

Overnight he had a manager and a nickname—the Boston Brawler. His face appeared on fight posters, and his name climbed up to the top of the listings. And afterward, in the pubs and clubs, we drank and danced and felt the glorious relief of those who’d outwitted fate. With our pockets crammed full of bills from Mickey’s winnings, the future was ours for the taking.

Mick was my champion, punching his way out of this drab, relentless grind into a new life of unfettered possibility.

Only it turned out Mick was a good boxer, not a great one. Someone else came along, an Italian; they called him the Boston Basher, and Mick couldn’t seem to get out from under his shadow.

And then I got pregnant. Suddenly our limitless future shrank to the size of a one-bedroom walk-up in the South End and a dockworker’s pay packet.

He would’ve married me, had I told him. But I never did. I didn’t tell anyone.

I went to New York instead. There was more work there, I said; better opportunities and a chance to really make something of myself.

We talked about what we would do, how we would live when I got back. But we both knew that wasn’t going to happen.

And Mick was such a stand-up guy, he even loaned me the money to leave him.

The Casino Athletic Club on Tremont Street was located up a steep flight of stairs on the second floor of an old grain warehouse. It smelled of generations of young men, training nonstop, in all seasons; of sweat, fear, and ambition. As soon as I stepped inside, a thick sticky wall of perspiration engulfed me. There were four rings, one in each corner, weights, punchbags; the sound of fists slamming against flesh and canvas beat out a constant dull tattoo. It was a familiar sound; I’d spent hours here, smoking and watching Mick train. Pausing in the doorway, I scanned the hall. Then I spotted him.

Mickey was in the far left-hand ring, sparring with a tall Negro man. His trainer, Sam Louis, was hunched over the ropes, shouting, “Look out, Mick! Come on! Look lively!”

And seated on a folding chair and wearing a molting chinchilla wrap over a cheap red dress was Hildy.

Of course.

Poor old Hildy was a permanent fixture at the Casino Club and something of a running joke. When she was younger, she’d worked in the office. With her blond German hair and blue eyes, she broke her fair share of hearts. But as the years passed, her sharp tongue and ruthless gold digging earned her the nickname Sour Kraut. Now she moved from man to man, shamelessly latching on to anyone she could. I looked around and wondered which of these saps she’d been bleeding dry lately. It had to be someone new, someone who didn’t know her game.

I watched as the other boxer, a big man, landed a heavy right to Mickey’s jaw. Sam blew the whistle and they stopped, heading back to their corners for water. Mickey spat out a mouthful of blood into a bucket and Sam mopped him down.

Now was my chance. As I moved through the gym, men stopped and a few catcalls and whistles followed. I knew better than to take it personally—it was just because I was a woman in a place women didn’t go—but I flattered myself into thinking that I was still worth whistling at.

Across the room, Hildy looked up, irritated that someone else was getting attention. And when she saw me, her eyes narrowed and her mouth twisted tight. Tossing the magazine down, she flounced over, barring my way. “What are you doing here?”

“Hi, Hildy.” I looked past her to where Mickey was doubled over, hands on knees, catching his breath. He hadn’t seen me yet. “I need to talk to Mickey.”

“What for?” She had a honking Boston twang and far too many facial expressions. Right now she was glaring, gaping, and smirking, all at the same time.

“What’s it to you, anyway?”

Across the room, Sam gestured at us, and Mick looked up. Surprise spread across his face. I gave a little wave.

He said something to his partner, who nodded, and climbed out of the ring.

“I’ll tell you what it is to me: you owe us money!” Hildy spat the words out.