По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

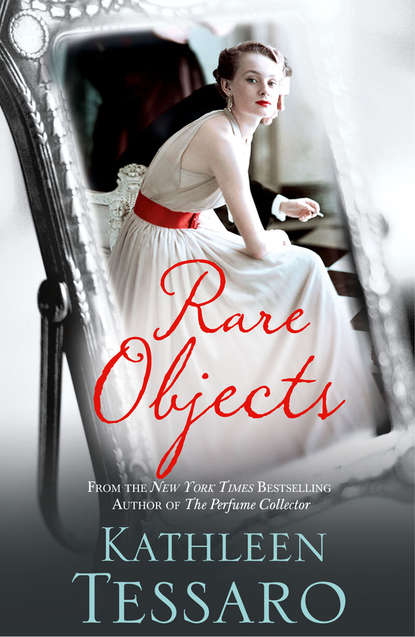

Rare Objects

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You’ll see.” The nurse gave her a terse smile. “It will be over before you know it.”

Instinctively, the girl reached for the pearls but they were gone now; confiscated by the staff. She wrapped her arms around herself and curled inward.

I hadn’t liked her much before, or rather I’d resented the way she’d swanned in, pretending to know everything. But now I felt for her, bent double with apprehension, cradling her dread like a mother with an infant.

We sat for a few minutes before she said, quite softly, “Tell me about a time when you were happy.”

Normally I would’ve ignored her. But today I was getting out, about to be free again and in the unique position to give her what she was asking for—hope.

I thought a moment. “There was the time at my second cousin Sinead’s wedding, after the ceremony, when we were in the church hall, having a ceilidh.”

“A what?”

“A ceilidh. It’s an Irish word. It means a dance, but with traditional music, proper reels. There’s always lots to drink, plenty of food, people fighting …”

“At a wedding?”

“Wouldn’t be an Irish wedding without it.” I leaned forward, elbows on my knees. “You see, the first thing you need to understand is that I was tall for my age. I’ve always been too tall. And skinny as a broom—no figure to speak of. So I was never much to look at as a kid, and I always felt pretty awkward. But that night I had one important advantage. My mother, she’s a very good dancer, and she taught me. A step dancer, they call it. There’s quite a lot of fancy footwork involved, and it takes real skill. For some reason I was good at it too, which was a miracle because I was all arms and legs. But when I got going and felt the music pulsing through me, I could really dance. And that night, for the first time in my life, I was nothing short of magnificent, dancing with everyone, showing off.” I smiled a little. “People stood round and watched me, clapping and cheering!”

The door at the end of the hall opened again, closed.

The girl’s face drained of color. “Go on,” she said. “Then what happened?”

“Some of the men took to teasing me. I suppose I looked ridiculous bouncing up and down with my red hair. They were calling me Matchstick because I was so thin, and my hair, well, I guess it looked like a flame. I wanted to get even with them, show them. So when the band took a break, they offered me a whiskey. I think they were trying to make a fool of me. I’d never had one before, but I lied, I told them I had. And then I drank it down in one. I don’t know how I did it, but I managed not to cough or choke. Well, that shocked them.”

“I’ll bet it did!”

“They thought it was funny. ‘She holds her whiskey like a man!’” I could still remember the way the liquor felt, burning down the back of my throat like fire. How it hit me like a punch to the stomach. It was like I’d never been born until then. Everything inside me suddenly felt warm and right and comfortable. “So they gave me another and I drank that too. Same thing, right back. And now I was their mascot, see. And when the band came back, I danced even harder.”

“So you were the belle of the ball.” She wanted to believe in fairy tales today, happy endings.

“Well, not quite.”

“Maybe you’ll do that again someday. When you get out.” Her eyes scanned my face, searching for something to cling to. “Don’t you think?”

“Sure. Maybe.”

I didn’t tell her that at some point my legs gave out, and the next thing I knew I was being sick, out in the alleyway behind the church. One of the men took me out, tried to hide me from my mother. I was dreadfully ill the next morning. Ma made an awful fuss with my cousin, and we never went to another ceilidh again.

“Your turn,” I said. “Tell me about a time you were happy.”

She looked out of the window covered in metal mesh that separated us from the sharp winter air, from the blue skies, snow, and sunshine. “I don’t have any memories. That’s why I’m here. To get rid of them all.”

BOSTON, FEBRUARY 1932 (#ulink_80bfb354-6e3c-5d37-9bd9-7fed2f90098e)

On the way home from my new job, I stopped by Panificio Russo on Prince Street. Open for business from six every morning till late at night, it was more than a bakery, it was a local institution. Just before dawn you could smell the bread baking, perfuming the cold morning air. Rich butter biscuits, dozens of different cannoli and biscotti, delicately layered sfogliatelle and zeppole, little Italian doughnuts, were made fresh each day. Traditional southern Italian cakes like cassata siciliana vied for space with airy ciabatta and hearty stromboli stuffed with cheese and meats, and fragrant panmarino made with raisins and scented with rosemary, all stacked in neat rows. Three small wooden tables sat by the front window, in the sun, where the anziani, the elderly men of the community, sipped espresso and advised on all manner of local business.

Well known throughout Boston, Russo’s delivered baked goods to many restaurants and hotels in the city. But they were first and foremost a family-run business and a proud cornerstone of North End life. It was widely known that once Russo’s ovens were hot and their own bread under way, poorer families from the tenements were welcome to bring their own dough, proofed and ready, to the kitchen door to be baked. Children waited in the back alleyway, playing tag and kick-the-can until the loaf was pulled out and wrapped in newspaper so they could hurry home with it, still hot. When a family finally graduated in fortunes from the alleyway to buying their bread from the front of the shop, Umberto Russo proudly served the woman himself, and his son Alfonso would make a treat of a few choice pastries.

I’d grown up with the Russo children and could remember when the bakery was little more than a single room with an oven. They were famous for their tangy sweet zaletti, dense breakfast rolls flavored with orange rind, vanilla, and raisins, and covered in powdered sugar. There was a time when I’d come in every morning to get one on my way to work. It had been a while since I’d been able to afford such treats, but now things were looking up.

The front of the shop was run by the three Russo women, sisters Pina and Angela and the formidable Maddalena Russo, their mother. They were all small and voluptuous, their figures accented by the white aprons pulled tight round their waists. I watched for my chance to catch Angela’s eye as she bustled from one end of the counter to the other, slipping between her mother and sister in an unending, seamless dance as they ducked down, reached over, slid around, or stretched high to grab the string hanging from the dispenser to tie the boxes tight. Above them, a picture of the Virgin Mary smiled calmly, radiating feminine modesty.

With her broad round face and large brown doe eyes, Angela looked just like the portrait of the Holy Mother that watched over them. Her hair curled gently, spilling out of her black crocheted hairnet to cascade softly on her cheeks. And she had a natural grace and gentleness that belied her often surprisingly sharp sense of humor.

I tried to remember the first time I’d met Angela and the Russo family but couldn’t. They’d simply always been there. For a while we’d all lived in the same tenement building, the one I still lived in now. The Russo children, especially the older boys, had “owned” the front stoop by virtue of being in the building the longest, but were gracious about sharing it with us younger ones. Angela and I were inseparable growing up: playing jacks and skipping rope, making little woolen dolls from old socks with button eyes that we pushed up and down the block in a broken-down old baby buggy that was used for everything from grocery shopping to junk collection. I was on my own a lot during the day while Ma worked piecing blouses together. But Mrs. Russo always made an extra place for me at her table, even though she already had five mouths to feed.

Angela and I made plans to run away from home and become professional dancers at eight; fell in love with the same boy, Aldo Freni, with his unusually long dark lashes, at ten; and were caught stealing lip rouge from the drugstore at thirteen, and received the same number of lashes as a result. She was the closest thing I had to a sister. And yet it was months since we’d spoken. My shame at my circumstances in New York had prevented me from writing, and she’d gotten married while I was in the hospital, a wedding I was meant to take part in as the maid of honor. Pina had to step in instead. Ma made excuses for me, told them the same tales I told her of eccentric millionaire bosses and unexpected trips abroad. But now that I was here, I felt a sudden attack of nerves and regret. The Russos knew me, could see past all my fictions.

It was Pina who spotted me first. When I left for New York, Pina was a newlywed. Now she was heavily pregnant. But though she may have enjoyed the rosy-cheeked sensuousness of a Rubens nude, there was nothing soft in her manner. “Oh, my, my!” She thrust her chin at me. “Look what the cat’s dragged in! Jean Harlow!”

Angela turned, and her face lit up. “Ciao, bella!” She made it sound light and natural, as if she’d only seen me the other day. “I didn’t recognize you! What have you done to your hair?”

The tension in my chest eased. Still, I couldn’t help noticing the wedding band that flashed, catching the morning sun as Angela expertly whipped the string around a cake box and tied it in a knot.

“Mamma mia!” Angela’s mother gasped, holding her palms to the heavens. “Maeve! What have you done to your beautiful red hair?”

All eyes turned.

“I cut it and … well …” I was turning red. “It’s for a job, actually.”

Pina snorted. “What, are you a Ziegfeld girl now?”

“Not exactly. A salesclerk. But no Irish.”

There was a time when the city was full of signs declaring “No Irish Need Apply.” We were considered little more than vermin. Then the Italians came, and suddenly we moved up a little in the world, only not quite far enough.

“Yeah, well, I’m surprised to see you here at all.” Pina folded her arms across her chest. “I thought this town wasn’t good enough for you. That only New York City would do.”

“Stop it!” Angela glared at her sister. “Just because you’ve never left Boston!”

“I don’t need to leave Boston. And evidently neither do you!” Pina laughed, nodding at me. “I hope you left a trail of bread crumbs so you could find your way home.” Pina always had a tongue like a stiletto blade. Even as a kid, she had a preternatural talent for verbal vivisection.

“Basta!” Her mother shot Pina a look. “We’ve missed you. Your mother told us you had important business in New York and couldn’t come to the wedding,” she continued evenly, resting her hands on her hips. “We’re sorry you couldn’t get away.”

Guilt stung beneath my smile.

“I’m sorry too. I mean …” I looked across at Angela; I was speaking to her more than anyone else. “I was working as a private secretary for a very wealthy man. Quite a difficult character, very demanding … I wanted to come, really I did.”

We all knew I wasn’t being honest. My story didn’t explain why I hadn’t written or called.

“Well, I’m just glad you’re here now,” Angela said, in that way she had of simply closing the door on anything difficult or unpleasant. “It’s good to have you back.” Then, popping a fresh loaf of bread into a paper bag and handing it across the counter to Mr. Ventadino, she flashed me a naughty smile. “La mia bella dai capelli biondi!”

“Ah, bella!” Mr. Ventadino laughed, eyeing me up and down. “Moltobella!”

The old men at the tables by the window laughed too, and Mrs. Russo rolled her eyes. “Girls! Comportatevi bene!”

Comportatevi bene—Italian for “behave yourself”—was the constant refrain of our childhood. When we were together, five minutes didn’t go by without Mrs. Russo saying it, usually with a rolled-up newspaper in her hand, ready to whack one or both of us on the back of the head.