По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

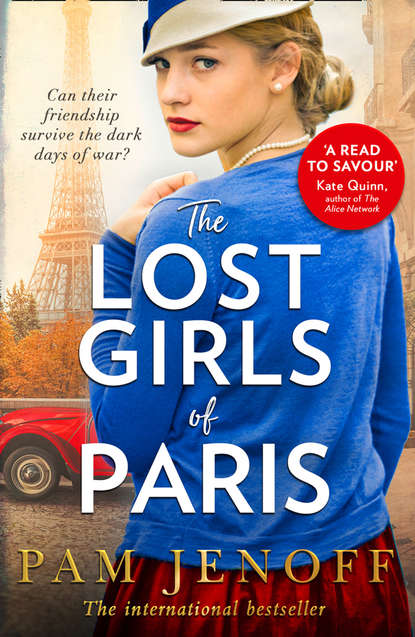

The Lost Girls Of Paris

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“She found me, too,” Brya added. “In a typing pool in Essex.” Each, it seemed, had been selected by Eleanor personally.

“Eleanor designed the training for us,” Josie said in a low voice. “And she decides where we will go and what our assignment might be.”

So much power, Marie thought. Remembering how cold and disdainful Eleanor seemed during their initial meeting in London, Marie wondered if this perhaps did not bode well for her.

“I like her,” Marie said. Despite Eleanor’s undeniable coldness, she possessed a strength that Marie admired greatly.

“I don’t,” Brya replied. “She’s so cold and she thinks she’s so much better than us. Why doesn’t she put on a uniform and fly to France herself if she can do better?”

“She tried,” Josie said quietly. “She’s asked to go a dozen times, or so I’ve heard.” Josie had an endless network of connections and sources. She made friends with everyone from the kitchen staff to the instructors and those relationships provided valuable bits of information. “But the answer is always the same. She has to remain at headquarters because her real value is here getting the lot of us ready.”

Watching Eleanor on the balcony, looking out of place and almost ill at ease, Marie wondered if it might be lonely to stand in her place, and whether she sometimes wished she was one of them.

The girls finished their breakfast swiftly. Fifteen minutes later, they slipped into the lecture hall. A dozen desks were lined three by four, a radio set atop each. The instructor had posted the assignment, a complex message to be decoded and sent. Eleanor was in the corner of the room, Marie noticed, watching them intently.

Marie found her seat at the wireless and put on the headset. It was an odd contraption, sort of like a radio on which one might listen to music or the BBC, only laid flat inside a suitcase and with more knobs and dials. There was a small unit at the top of the set for transmitting, another below it for receiving. The socket for the power adapter was to the right side, and there was a spares kit, a pocket with extra parts to the left. The spares pocket also contained four crystals, each of which could be inserted in a slot on the radio to enable transmission on a different frequency.

While the others started working on the message on the board, Marie looked down at the paper the instructor had left for her to take the retest. It was the text of a Shakespeare poem:

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed that they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

The message first had to be coded through a cipher. The ciphers were contained in a small satchel, each printed on an individual square of silk, one inch long by one inch wide. Each silk contained what was called a “worked-out key,” a printed onetime cipher that would change each letter to another (for example, in this key, a became m and o became w) until the whole message made no sense at all to the naked eye. Each cipher was to be used to code the message, then discarded. Marie changed the letters in the message into the code given on the cipher and wrote down the coded message. She lit a match and burned the silk cipher as she’d been taught.

Then she began to tap out the message using the telegraph key. Marie had spent weeks learning to tap out the letters in Morse code and had spent so much time practicing she had even begun to dream in it. But she still struggled to tap swiftly and smoothly and not make mistakes, as she would need to in the field.

Operating the wireless, though, was more than a matter of simple coding and Morse. During her first week of training, the W/T instructor, a young lieutenant who had been seconded to SOE from Bletchley Park, had pulled her aside. “We have to record your fist print and give you your security checks.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You see, radios are interchangeable—if someone has the coils and the crystals to set the frequency, the transmission will work. Anyone who gets his hands on those can use the radio to transmit. The only thing that lets headquarters know it is really you is your security checks and your fist print.”

The instructor continued, “First, your fist print. Type a message to me about the weather.”

“Uncoded?”

“Yes, just type.” Though it seemed an odd request to Marie, she did it without question, writing a line about how the weather changed quickly here, storms blowing through one moment and giving way to sunshine the next. She looked up. “Keep going. It can be about anything really, except your personal background. The message needs to be several lines long for us to understand your fist print.”

Puzzled, Marie complied. “There,” she said when she had filled the page with nonsense, a story about an unexpected snowstorm the previous spring that had left snow on blooming daffodils.

The transmission printed on the teletype at the front of the room. The instructor retrieved it and held it up. “You see, this is your fist print, heavy on the first part of each word with a long pause between sentences.”

“You can tell that from a single transmission?”

“Yes, although we have your other transmissions from training on file to compare.” Though it made sense, Marie hadn’t considered until that moment that they might have a file on her. “But really, it doesn’t change from session to session. You see, your fist print is like your handwriting or signature, a style that identifies your transmission as uniquely you. How hard you strike the transmission key, the time and spacing between letters. Every radio agent has her own fist print. That’s one of the ways we know it is you.”

“Can I vary my fist print as kind of a signal if something is wrong?”

“No, it is very hard to communicate unlike oneself. Think about it—you don’t choose your handwriting consciously. It just flows. If you wanted to write really differently, you might need to switch to your nondominant hand. Same with your fist print—it’s subconscious and you can’t really change it. Instead, if something is wrong, you must let us know in other ways. That’s what the security checks are for.”

The instructor had gone on to explain that each agent had a security check, a built-in quirk in her typing that the reader would pick up to know that it was her. For Marie, it was always making a “mistake” and typing p as the thirty-fifth letter in the message. There was a second security check, too, substituting k where a c belonged every other time a k appeared in the message. “The first security check is known as the ‘bluff check,’” the instructor explained. “The Germans know we have checks, you see, and they will try to get yours out of you. You can give away the bluff check if questioned.” Imagining it, Marie shuddered inwardly. “But it’s the second check, the true check, that really verifies the message. You must not give it up under any circumstances.”

Marie completed the retest now, making sure to include both her bluff and true checks. She looked behind her. Eleanor was still there and she seemed to be watching her specifically. Pushing down her uneasiness, Marie started on the assignment on the board, picking up speed as she worked through the longer message with a new silk cipher. A few minutes later, Marie finished typing the message. She looked up, feeling pleased.

But Eleanor ripped the transmission off the teletype and strode toward her with a scowl. “No, no!” she said, sounding frustrated. Marie was puzzled. She had typed the message correctly. “It isn’t enough to simply bang at the wireless like a piano. You must communicate through the radio and ‘speak’ naturally so that your fist print comes through.”

Marie wanted to protest that she had done that, or at least ask what Eleanor meant. But before she had the chance, Eleanor reached over and yanked the telegraph key from the wireless. “What on earth!” Marie cried. Eleanor did not answer but picked up a screwdriver and continued dismantling the set, tearing it apart piece by piece with such force that screws and bolts clattered across the floor, disappearing under the tables. The other girls watched in stunned silence. Even the instructor looked taken aback.

“Oh!” Marie cried, scrambling for the pieces. She realized in that moment she felt a kind of connection to the physical machine, the same one she had worked with since her arrival.

“It isn’t enough just to be able to operate the wireless,” Eleanor said disdainfully. “You have to be able to fix it, build it from the ground up. You have ten minutes to put it together again.” Eleanor walked away. Marie’s anger grew. This was more than payback for her earlier outburst; Eleanor wanted her to fail.

Marie stared at the dismantled pieces of the wireless set. She tried to recall the manual she’d studied at the beginning of W/T training, trying to envision the inside of the wireless set in her mind. But it was impossible.

Josie came to her side then. “Start here,” she said, righting a piece of the machine’s base that had fallen on its side and holding it so that Marie could reattach the baseplate. As she worked, the other girls stood and helped to gather the pieces that had scattered, going on hands and knees for the missing bolts. “Here,” Josie said, handing her a knob that screwed into the transmitter. She managed to tighten a screw Marie was struggling with, her tiny fingers quick and deft. Josie pointed to a place where she had not inserted a bolt just right.

At last the machine was reassembled. But would it transmit? Marie tapped the telegraph key, waited. There was a quiet click, a registering of the code she had entered. The radio worked once more.

Marie looked up from her work, wanting to see Eleanor’s reaction. But Eleanor had already left.

“Why does she hate you so much?” Josie whispered as the others returned to their seats.

Marie didn’t answer. Her spine stiffened. Not bothering to ask permission, Marie stormed from the hall, looking into doorways until she found Eleanor in an empty office, reviewing a file. “Why are you so hard on me? Do you hate me?” Marie demanded, repeating Josie’s question. “Did you come here just to finish me off?”

Eleanor looked up. “This isn’t personal. You either have what it takes or you don’t.”

“And you think I don’t.”

“It doesn’t matter what I think. I’ve read your file.” Until that moment, Marie had not considered what it might say about her. “You are defeating yourself.”

“My French is as good as any of the others, even the men.”