По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

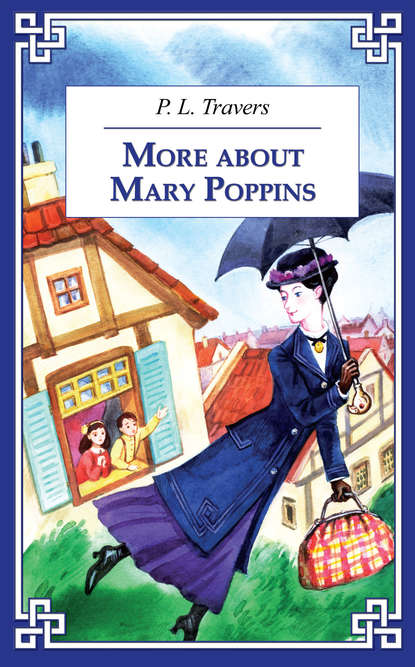

More about Mary Poppins / И снова о Мэри Поппинз

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What’s my name? What’s my name? What’s my name?” cried the Starling in a shrill anxious voice.

“Er-umph!” said John, opening his mouth and putting the leg of the woolly lamb into it.

With a little shake of the head the Starling turned away.

“So – it’s happened,” he said quietly to Mary Poppins.

She nodded.

The Starling gazed dejectedly for a moment at the Twins. Then he shrugged his speckled shoulders.

“Oh, well – I knew it would. Always told ’em so. But they wouldn’t believe it.” He remained silent for a little while, staring into the cots. Then he shook himself vigorously.

“Well, well. I must be off. Back to my chimney. It will need a spring-cleaning*, I’ll be bound.*” He flew on to the window-sill and paused, looking back over his shoulder.

“It’ll seem funny without them, though. Always liked talking to them – so I did. I shall miss them.”

He brushed his wing quickly across his eyes.

“Crying?” jeered Mary Poppins. The Starling drew himself up.

“Crying? Certainly not. I have – er – a slight cold, caught on my return journey – that’s all. Yes, a slight cold. Nothing serious.” He darted up to the window-pane, brushed down his breast-feathers with his beak and then, “Cheerio!” he said perkily, and spread his wings and was gone…

Full Moon

All day long Mary Poppins had been in a hurry, and when she was in a hurry she was always cross.

Everything Jane did was bad, everything Michael did was worse. She even snapped at the Twins.

Jane and Michael kept out of her way as much as possible, for they knew that there were times when it was better not to be seen or heard by Mary Poppins.

“I wish we were invisible,” said Michael, when Mary Poppins had told him that the very sight of him was more than any self-respecting person could be expected to stand.

“We shall be,” said Jane, “if we go behind the sofa. We can count the money in our money-boxes, and she may be better after she’s had her supper.”

So they did that.

“Sixpence and four pennies – that’s tenpence, and a halfpenny and a threepenny-bit,” said Jane, counting up quickly.

“Four pennies and three farthings and – and that’s all,” sighed Michael, putting his money in a little heap.

“That’ll do nicely for the poor-box,” said Mary Poppins, looking over the arm of the sofa and sniffing.

“Oh no,” said Michael reproachfully. “It’s for myself. I’m saving.”

“Huh – for one of those aeryoplanes*, I suppose!” said Mary Poppins scornfully.

“No, for an elephant – a private one for myself, like Lizzie at the Zoo. I could take you for rides then,” said Michael, half-looking and half-not-looking at her to see how she would take it.

“Humph,” said Mary Poppins, “what an idea!” But they could see she was not quite so cross as before.

“I wonder,” said Michael thoughtfully, “what happens in the Zoo at night, when everybody’s gone home?”

“Care killed a cat,*” snapped Mary Poppins.

“I wasn’t caring, I was only wondering,” corrected Michael.

“Do you know?” he enquired of Mary Poppins, who was whisking the crumbs off the table in double-quick time.

“One more question from you – and spit-spot, to bed you go!” she said, and began to tidy the Nursery so busily that she looked more like a whirlwind in a cap and apron than a human being.

“It’s no good asking her. She knows everything, but she never tells,” said Jane.

“What’s the good of knowing if you don’t tell anyone?” grumbled Michael, but he said it under his breath so that Mary Poppins couldn’t hear…

Jane and Michael could never remember having been put to bed so quickly as they were that night. Mary Poppins blew out the light very early, and went away as hurriedly as though all the winds of the world were blowing behind her.

It seemed to them that they had been there no time, however, when they heard a low voice whispering at the door.

“Hurry, Jane and Michael!” said the voice. “Get some things on and hurry!”

They jumped out of their beds, surprised and startled.

“Come on,” said Jane. “Something’s happening.” And she began to rummage for some clothes in the darkness.

“Hurry!” called the voice again.

“Oh dear, all I can find is my sailor hat and a pair of gloves!” said Michael, running round the room pulling at drawers and feeling along shelves.

“Those’ll do. Put them on. It isn’t cold. Come on.”

Jane herself had only been able to find a little coat of John’s, but she squeezed her arms into it and opened the door. There was nobody there, but they seemed to hear something hurrying away down the stairs. Jane and Michael followed. Whatever it was, or whoever it was, kept continually in front of them. They never saw it, but they had the distinct sensation of being led on and on by something that constantly beckoned them to follow. Presently they were in the Lane, their slippers making a soft hissing noise on the pavement as they scurried along.

“Hurry!” urged the voice again from a near-by corner, but when they turned it they could still see nothing. They began to run, hand in hand, following the voice down streets, through alley-ways, under arches and across Parks until, panting and breathless, they were brought to a standstill beside a large turnstile in a wall.

“Here you are!” said the voice.

“Where?” called Michael to it. But there was no reply. Jane moved towards the turnstile, dragging Michael by the hand.

“Look!” she said. “Don’t you see where we are? It’s the Zoo!”

A very bright full moon was shining in the sky and by its light Michael examined the iron grating and looked through the bars. Of course! How silly of him not to have known it was the Zoo!

“But how shall we get in?” he said. “We’ve no money.”

“That’s all right!” said a deep, gruff voice from within. “Special Visitors allowed in free tonight. Push the wheel, please!”

Jane and Michael pushed and were through the turnstile in a second.