По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

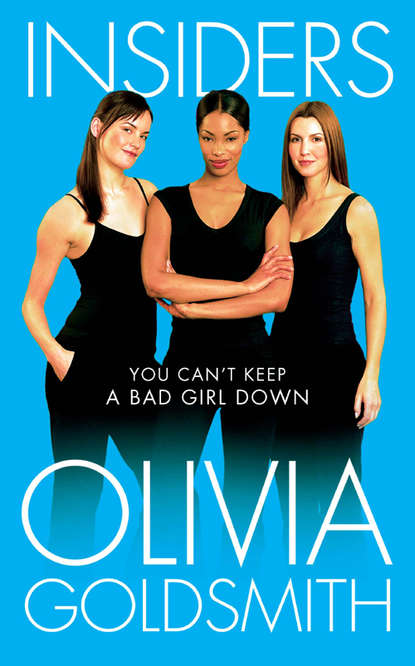

Insiders

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The woman was pushed back into a hard black plastic chair that sat as low to the ground as a beach chair. Officer Byrd obstructed Jennifer’s view for a few moments but, when he finally moved, Jennifer was horrified to see that the woman had been strapped into the chair at the legs. Then the straitjacket was slowly removed from the woman’s body, and the straps were brought over her shoulders in much the same way that an astronaut would be strapped to his seat.

Jennifer, terrified but unable to move, watched as they struggled to wheel the woman past her window. For a moment the startling blue eyes of the African American woman gave Jennifer an intimate look, certainly not one of apology. She winked at Jennifer. Then she was gone.

Jennifer, shocked, didn’t know how long she had stood there. There was a drain in the cement floor that gurgled.

She waited for a little while, hoping that the guard would return so she could demand some better conditions. But no one came. Finally she balanced on one leg and peeled off first one drenched sock, then the other. She squeezed them out over the drain. At least half a cup of water ran into the sewage hole, but Jennifer’s problem wasn’t solved. Now, without socks, her feet were frozen. She couldn’t sit on the mattress because it was also disgustingly wet. She didn’t know what the correction officer had done with the troublesome woman. Did they have a firing squad here at Jennings? Could she scream for help or attention? She found she couldn’t do it. The woman’s blue, blue eye winking at her, as if they were … together or … bonded somehow had really shaken her. Then she saw, with relief, that Officer Byrd was at the end of the hall about to pass by. Finally she knocked on the glass and he turned to her.

‘I’m wet,’ she said. ‘This whole room has been ruined. You have to help me.’ The fear in her voice only made her more frightened.

But Byrd didn’t have a clue. He turned his mouth to his squawk box and said something. He stepped into the room and turned around.

‘Tsk, tsk,’ he said. ‘You got more than you bargained for.’ Jennifer decided not to even respond. Then he looked her over. It was a sexual leer, and she could tell that he wanted her to be uncomfortable. ‘I’m alone up here now,’ he explained. ‘They had to take that one down to the hold. It was her first day in.’

Jennifer actually shivered. ‘They’ll be back soon,’ she said in a flat voice. What kind of man took a job in a women’s prison and then tried to …

‘Well,’ said Byrd, ‘I could take you down to a cell below six. That’s where the nigger was. She used her towel to stop up the toilet and caused a major flood.’ Jennifer recoiled both at the word he’d used and because he’d moved toward her. His voice insinuated that … Just then his walkie-talkie spoke.

Roughly Byrd took her under her right arm and moved her out of her little glass box. He was rubbing up against her as they walked past the place where the mad woman had been imprisoned, then moved her to number four, a cell exactly like her previous one.

‘Chow will be in a minute,’ he said as he slowly released his grip and ran his hand down her arm.

‘Food?’ Jennifer cried. ‘I can’t even breathe.’ Then she remembered her outfit. ‘And I need a new jumpsuit. This one is wet.’

‘We’ll have supper for you right away,’ Byrd said. ‘But we can’t issue another uniform. Laundry’s closed.’ Then he moved a little closer. ‘Of course,’ he almost whispered, ‘you could take it off and hang it up. There’s nobody here to see you.’

Jennifer looked around at the observation windows, the open ceiling, and the catwalk above. Now she was grateful for them. She wanted someone to keep their eyes on Byrd – or Vulture. But she had a creepy feeling that most of those eyes would get a big kick out of her standing around naked. And would they intervene if Vulture touched her?

‘Maybe I could get you something else to wear,’ he said now, ‘if you wanted to be friendly,’ he added.

She couldn’t believe what she was hearing. It was a sexual innuendo, wasn’t it? ‘Forget about that,’ she told Byrd.

He shrugged. Had he just offered her something in return for sex? She kept her face calm but swore to herself that she’d have him reported to the governor by tomorrow afternoon. ‘Too bad. You’ll have to wear the damp one until morning,’ he said. He locked the door on the new cubicle and left.

Jennifer was deeply grateful for that. She would have spent some time examining the cell if it hadn’t been quite so obviously identical to the previous one. She’d even be willing to swear in a court of law that the stains in this mattress were shaped identically to the one on the other. Hadn’t there been that blot that looked like the state of Florida on the upper left corner of the previous mattress? The wetness against her ankles was terribly cold and the rough polyester chafed, but otherwise all was the same. Except that this time, when she sat down in her corner, her stomach rumbled loudly enough for her to hear, and maybe loudly enough for the woman in the next room – if there was a woman in the next room – to hear as well.

But she was still determined that she wouldn’t eat anything. And she wouldn’t lie down. Even though the day seemed a hundred hours long, she wouldn’t allow her hunger or fatigue to get the better of her.

She leaned her back against the wall, pulled her knees up to her chest, wrapped her arms around her cold ankles and tried, once again, to close her eyes and imagine what treats would come her way when she went back to her real life. Donald had better be especially generous with her bonus. In fact, she might not have to wait until the end of the fiscal year. Of course, after December there would be the full partnership and the big office. She took a deeper breath of the fatal air. Concentrate on it, she told herself. Think how beautiful that place will be compared with this one. She knew each partner got a generous budget to furnish and decorate his or her office, but now she thought that she might move her reproduction Beidermeyer desk from home into the office. She’d bill Hudson, Van Schaank and use the money for the dressing table she’d admired in the antique shop on upper Lexington Avenue. She’d … she tried once again to get into the reverie but it wasn’t working.

She opened her eyes. She couldn’t really imagine anything but this room, her freezing feet, the unbearable light and the hunger gnawing at her belly. She tried to remind herself that she was the hero of the Vareen takeover and the heavy lifter in the Cooper Corp. scenario, but she hadn’t been cold and wet and humiliated then. Jennifer may have managed not to drink and not to use the ladies’ room, but if she had had to pee then, she wouldn’t have had to do it in front of a dozen pairs of eyes.

She felt her eyes begin to get wet and forced herself to stand up. Just then a noise outside the cell brought her to the front. Another guard was wheeling a trolley down the corridor. When he reached her, he didn’t even look up. He merely bent toward her, his face forward, and slipped a plastic tray through the slot. It almost looked like an airplane meal.

‘No,’ she told herself firmly one more time. But her cold feet walked, without her permission, over to the tray. She bent and picked it up. Something green. Something brown. And something that looked like it had tomato sauce on it. Whatever it was, she took it to the bed, sat down crosslegged on the filthy mattress, and ravenously wolfed it down.

7 Maggie Rafferty (#ulink_4eb327fb-757e-5712-ad58-1ef22ea4751e)

I was a prisoner long before I was an inmate.

Bonnie Foreshaw, inmate. Andi Rierden, The Farm

I know that it will seem a truism, but I must say that shooting your husband, accidentally or otherwise – and even more – having him die from the bullet wound, totally changes your life. The chief benefit is, of course, that he is gone, but there are other benefits, which I’ll get to later. The main drawback, however, is that in most cases you’re deprived of your liberty and might have to live in a place with a library that has only one hundred and sixteen books. That is the exact number of books in the library here at Jennings.

But back to my husband. He could have lived; he died just to spite me. The bullet only grazed his aorta. Serious? Yes – but with his will power, he might have lingered long enough for the paramedics to stabilize him. But no. He always had to get his way in the end. He could turn any situation to his advantage. This was, of course, only one of the many reasons why I hated him so fully and completely, and why the gun I was holding went off while it was pointed in his direction. At the time, I had meant to kill myself. How foolish of me.

My husband was the famous Richard Rafferty, Riff to his friends. At the very minute the bullet was nicking his deceitful heart, his latest book, The Life of the Heart, was being talked about on the six o’clock news. A book? On the evening news? How can that be? Easy. Richard was sleeping with the woman who produced the show.

And speaking of the evening news, I understand that the new arrival, this Miss Jennifer Spencer, is up in observation hell. She’s certainly been news. I’ve been following her story with some interest, since one needs such pastimes in prison, and because both of my sons are in the same type of business as she is … or was. From the beginning I could see that she was taking the fall for someone else, probably a man. The only question that remained in my mind was, did she know what was going on? Was she complicitous? I was actually looking forward to seeing her in person, because then I would know.

How would I know? Well, let me explain another result of happening to murder your husband: It turns your brain inside out. Although this is terribly painful at the time and for a long while afterward, in the end it is a good thing. I know this sounds totally insane, but I am a better person for having killed my husband. For instance, I’ve become nearly as good as a dog at reading people.

Lest anyone think that I am advocating murder as a method of self-improvement, let me correct that impression at once. Yes, I am a better person, but I was a good enough person before. Riff wasn’t; he wasn’t worth dirtying my hands for. What he deserved from me was the indifference that I only now feel toward him. Trading life and liberty for well-deserved revenge and an enlightened mind is a very hard deal to accept. Jennings, have I said it before, is a kind of hell.

When I arrived here, I fell into despair at once. The trial, Grand Guignol though it had been, was a reason to get up, get dressed, and perform. Here there was nothing. I wanted to die. Imagine. I had been headmistress of one of the most prestigious private girls’ schools on the East Coast, and had lived among the very rich and instructed their daughters. On my first day at Jennings, I was told to ‘get my fuckin’ ass movin’.’ I had been in Who’s Who In American Education. Here I was referred to as ‘the old bitch’.

Somehow I got used to the vulgarity. It was the deprivation of every sensory pleasure that was the hardest thing for me to bear. My marriage had not been happy, but I had lived in a beautiful home, traveled to Paris and London nearly every year, spent summers in Tuscany, was a connoisseur of wines and fine foods, collected rare books and Herend, drove an immaculate ‘62 Mercedes Gullwing, subscribed to the ballet, shopped at Neiman Marcus.

And suddenly I was confined to one of the ugliest places on the face of the earth, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. I assure you, no bleaker, duller, more visually offensive place can exist. I’d rather be in Craigmore Prison, dank dark dungeon that it is. It at least has some architecture to boast of. Jennings is the kind of dull, featureless maze they put rats into when they’re trying to see if they can stunt their brain development. Even crumbling ceilings or walls would add interest, but here there is no crumbling, just ugly, 1960s efficiency. Jennings was built when there was a soul-sickness plaguing the earth, probably an aftereffect of the war. Buildings were built to last, but beauty in architecture was eschewed. The style could be called ‘Plainness with a Vengeance’, ‘Ugly is Fine’, or ‘Death in Life’. And I have to stay here for the rest of mine. There are no aesthetic pardons.

So I wondered how Jennifer Spencer was faring in Observation. She had a lower-middle-class youth, upper-middle-class adulthood. A transition to Jennings wasn’t going to be easy for her, to say the least. But my interest in the fate and character of Jennifer Spencer was going to be limited compared to the keen interest I have in women like Movita Watson and her ‘sidekick’, Cher. I had never met women like them before my incarceration and I am fascinated by their unschooled intelligence.

Movita, for example, is someone I pegged as decent the minute I saw her despite her hellfire exterior. She plays tough, and sometimes dumb, but she’s generous and clever, too, and has her own eye for ‘attitude’ in others. She will tell you that when she entered Jennings, I had no ‘attitude’ at all. This was why we became friends fairly quickly. She was, in her words, ‘curious ‘bout that weird ol’ bitch’. Well, attitude is one of the petty attributes that I lost as a result of my husband dying at my hands, or more literally, at my feet. When I came in, I’ve been told by Movita, I had the look of a ‘schoolteacher who’d been wiped out by a nuclear bomb’. Change ‘schoolteacher’ to ‘schoolmistress’ and her assessment was pretty much accurate.

But those credentials as a schoolteacher secured my position as the prison librarian. And since that time I have been preoccupied with thinking of ways to acquire more books. Books were always important to me. Well, they are my life’s blood really. Before and after my crime.

The Life of the Heart (of which, ironically, we had two copies in the library) was Richard’s sixth book. It was supposed to be about the stunning and liberated life that can be ours if we give in to our feelings of love. He’d put me and my two sons through hell while he was trying to write it, just as he had, come to think of it, when he wrote his fourth and fifth. The children were ‘distractions’. Somehow I was always doing something ‘stupid’. He once accused me of turning pages too loudly. Bryce and Tyler, despite their initial business success, were ‘disappointments’ to him. But that I could understand. How disappointing it must be for a false, humorless, and arrogant man to have two sons who could see through him and laugh. I, on the other hand – raised to be a right-minded woman – supported the bastard throughout. I fed him, excused him, pampered him, read his drafts, corrected his grammar, gave him ideas, typed his corrections, and hated his editor with him. I did it for thirty-four years. Why stop now, when he needed me more than ever?

It is only now, seven years later, that I can look back at the situation without anger. As I said above, I am a better person now.

I knew that Jennifer Spencer would be given the orientation that included a tour of the facility, a bed assignment, and a work detail. I know what’s what here on my own, though I do appreciate the heads up I get when Frances delivers the ice with kites. I had to chuckle at the ‘kites on ice’. There is no work here in the library. The prison population consists of very few readers and what they would read doesn’t exist in the library. Needless to say, I would welcome Miss Spencer to Jennings when she came by later in the day. Lest you think otherwise, this would not be some warmhearted Shawshank Redemption nonsense where I take the girl under my wing. If I had wings, I assure you I’d fly the fuck out of here. Besides, I already have two sons – I don’t need a daughter. After a quarter century of girls’ schools, I know how much trouble they are.

Jennifer finally came to the library, with that Officer Camry, at about three-thirty, the time I usually fade out, having worked in schools all my life. She had the air of a young woman who was in trouble, there was no mistaking that. Her face was pale and drawn, her eyelids were swollen, and the eyes peering out from between them looked as if they’d glimpsed something horrific, but at the same time she still looked like someone whose car and driver were waiting for her. She had heavy attitude, Movita would say. But I could see right through that. The press, as usual, had gotten it wrong: Thanks to my twenty-seven years of working with schoolgirls, I could see that Jennifer had been a scholarship student. Determination to overcome obstacles was written all over her, so there had to have been obstacles. I could see that she had real strength to her, and that when the realization that she was going to be in here for some real time hit her, she would survive the shock.

‘Hello,’ I said. ‘I’m Maggie.’ I sounded ridiculous to myself, as if we were in some kind of meeting.

‘Hi,’ she answered. She was so not present that I was driven to speak to her again. ‘This is our library, such as it is.’

She blinked at me, as if she didn’t understand why I was talking to her. ‘We have the space,’ I went on, ‘but we have very few books.’

‘It doesn’t matter to me. Don’t worry about it,’ she said, a little sharply. Then her expression changed. She was looking at me, wondering who I was, I expect. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said then. ‘I don’t mean to be rude. It’s just that I’m not going to be living here. But this guard has been very nice.’ I saw Officer Camry stiffen. It’s funny about how prison guards refuse to be called prison guards.

‘He’s an officer, dear,’ I said in a voice drier than the paper of my books. ‘Not a guard. You call them officers or COs.’

‘Correction officer,’ Camry the fool added. He was harmless enough and I nodded at him.

‘Oh. Thank you,’ the girl said.

Jennifer Spencer surprised me in one way. I, who have met such a wide cross section of women when you consider both my students, my social circle, and my present comrades, could not tell if the girl was essentially good or bad. It’s the kind of thing I almost always know at a glance yet I didn’t know it then, although I do now. I could see that she was honest.