Claves del derecho de redes empresariales

In one of the first empirical studies in this area, a research group was able to shed light on business networks’ internal organizational processes (Albers, Schweiger & Gibb, 2013) by examining the instruments and processes a network uses to retain extant members, as well as to acquire new ones. The chosen context involved a large German tire retailing network named “RubberNet”, an alias for a real network to ensure confidentiality.

TABLE 1: Leading Tire Retailers in Germany (2012)

RankRetailerNo. of outlets (2012)1GDHS (Goodyear-Dunlop)9622Point S5523Vergölst (Continental)3614Euromaster (Michelin)3275Team3206EFR3107MLX (Meyer Lissendorf)3018First Stop (Bridgestone)225Source: BRV (2012).

The tire retailing industry in Germany was chosen for the window it offered into network rivalry. Today, 83 percent of German tire retailers are members of a network (BRV, 2012) that is used to increase purchasing power and enhance consumer awareness. Overall, the top eight retail networks each operate over 200 outlets within Germany (see table 1 for an overview).

RubberNet is a network of independent tire retailers operating as a legally constituted limited liability corporation. The relevant decision and activity levels in RubberNetare the network and retail member levels. The explorative empirical study identified three core acquisition and retention processes, that is, sensing, attracting, and securing, and found that the roles of two network organizational actor levels (the network’s central management unit, or headquarters (HQ)), and the retail member organizations, combine to serve as necessary linkers and enablers in acquiring and retaining members.

The sensing process refers to monitoring the industry context and the early identification of potential acquisition targets; that is, individual retailers in which changes in ownership and management have just taken place, or are likely to be effective soon. Rival networks members that are not satisfied with their situation in their current retailer system are also potential recruits. For RubberNet, sensing relies on an active membership base and strong connections with local small and medium enterprises. Another important factor is the availability of central management unit “coaches”; that is, network HQ employees that are assigned to a specific region in Germany to liaise with, and tutor regional members. They are the first contact for all members in case of any business-related issue and monitor relevant developments in the local industry environment, approaching competing retailers if they think this is appropriate. The network HQ itself also contributes to sensing by its central management team which systematically collects and analyzes industry news, both formal (for example, in industry news) and informal (for example, rumors on trade fairs). Overall, combining local retailers (member level) and network management (network HQ, network level) seems to be an effective means of increasing the membership base.

The second process, attracting, was found to be more analytical, and includes specific predefined service components, roles, procedures and even norms. These are driven and administered by the network HQ, with network members being comparatively passive. They can be activated if the need arises since a retailer-to-retailer talk is sometimes more effective than a manager-to-retailer talk, but the actual approach, negotiation, and contract closure is performed centrally via the network HQ and its staff.

This contrasts with the key process of securing, which addresses retaining existing members. In case of rival networks addressing RubberNet’s members, it is again a joint effort by the network HQ and co-members to retain them. However, in contrast to attracting, the extant member-retailer base plays the essential role since social mechanisms seem to be the most effective retention method. However, the network HQ plays a central role in encouraging and offering opportunities for these social bonding mechanisms. For example, the general assembly of all members is organized such that it allows members to meet and chat even before and after the “formal” meeting parts; a big and swaying dinner party is an important ritual that is included in the annual meeting program, as is the desire to involve the retailers’ families to allow for additional social bonds to develop. These social events are also encouraged on the regional level, and actively supported by the coaches as well. Potential candidates to leave the network are then addressed by co-members rather than the network HQ; this process is surprisingly effective.

Overall, this study shows that networks can have effective processes in place to attract and keep members in competitive environments. It also shows that, at least for networks of a non-trivial size, a balance between centrally administered, analytical processes and resources (for example, through a network central management organization) and more evolutionary, social processes is useful in achieving these goals (Albers et al., 2013).

The results of the study also indicate that networks should develop process and mechanism repertoires that enhance tactical flexibility. As shown herein, the two top level processes of attracting and securing follow different logics (analytical attracting process vs. evolutionary securing process) and involve the network actors in different roles.

Networks should also consider employing exit barriers for their members to inhibit members that want to leave. The distinct logic and the degree to which such barriers are used needs to be considered carefully as the ongoing membership of an unwilling and potentially destructive member might come at higher total costs than its value for the network.

Firms in network-intensive environments should watch networks closely and critically assess the perceived membership imperative. To do so, adequate criteria to evaluate membership benefits are required. Also, firms need to monitor attractive industry partners and pay attention to their network affiliation, as well as their goals and satisfaction degree, to optimize timing in their approach.

3.3. Competition in Network Governance

A final domain of decisive influence on network performance is its organization and ongoing management, an issue that is often addressed under the label of network, or alliance, governance (Albers, 2005). The failure of many networks is attributed to ineffective governance structures, involving either misaligned organization in their formation, or failure to adapt over time (Reuer, Zollo & Singh, 2002; Sampson, 2004).

At any given point in time, various governance solutions exist (Albers, 2010; Albers, Wohlgezogen & Zajac, 2013; Ebers & Oerlemans, 2013); therefore, networks compete on structures to manage their processes and members. Independent of their concrete parameter values and desig+n nuances, and thereby paying tribute to the sheer amount of possible configurations of organizations, institutional economists describe three essential forms of economic coordination: markets, hierarchies, and hybrids (Williamson, 1985, 1991). Each of these forms is, according to transaction cost economics (TCE), suitable (that is, efficient) in a different context. However, in some industries, different governance forms exist under seemingly similar conditions, also with regard to TCE’s criteria. For example, in the German less-than-truckload (LTL) business, a logistics market that generated overall revenue of more than €6 billion in 2010, business networks (“hybrids” in TCE) compete with integrated, large firms (“hierarchies” in TCE terms), as Table 2 shows.

TABLE 2: Top 10 firms in the German LTL market in 2008

Pos.OrganizationSales in €M1Dachser5942IDS (network)4503Deutsche Bahn425Schenker (Deutsche Bahn)4254System Alliance (network)4005Deutsche Post350DHL Express (Deutsche Post)3506CargoLine (network)3387CTL (network)335Hellmann (Partner System Alliance)310824plus (network)2489ABX Logistics20310S.T.a.R. (network)159Source: Albers &Klaas-Wissing (2012)

In this industry, six out of the top 10 players have consistently represented cooperative business networks over many years. The formation of LTL cooperation networks is seen as one of the most promising strategies by which small and medium-sized firms can build a geographically expanded and denser transportation network in order to generate economies of scale. In this setting, a well-organized network can create a competitive product portfolio to shippers and challenge the large integrated logistics corporations. In addition, it can compete with regard to inventing and testing organizational solutions (Klaas-Wissing & Albers, 2010). This question was targeted in an empirical analysis of two very different, yet seemingly successful networks in the German LTL business, called “Alpha” and “Beta” for reasons of confidentiality (Albers &Klaas-Wissing, 2012).251

The Alpha network has a turnover of more than one hundred million Euros and belongs to one of the largest LTL business networks in Germany. Members employ a privately held limited liability company (LLC) to serve as a central alliance management unit. The alliance offers a dense national transportation network, consisting of more than 130 local depots, owned by its more than 100 partner companies that are all small and medium-sized logistics firms. The partner companies are shareholders in the network HQ. In addition to its equity capital base from its members, Alpha LLC is financed by handling and administration service fees from the daily operational business with the partner companies.

In addition to the legal requirements that stem from the legal form of the network HQ (the LLC), Alpha’s network organization is influenced by two constitutive properties: the relatively large number of alliance members, and its business model value focus. Due to the large number of investing members who also hold similar Alpha equity proportions, voting rights are widely dispersed. Network members have only limited influence on managerial decisions concerning strategic matters. As a consequence, Alpha’s board of directors possesses extensive authority to define the strategy, set up the general operation rules, and design network infrastructure. In fact, a single member can either agree with the board’s strategic decisions or leave the alliance (exit option).

Regarding the value focus to its network partners, Alpha provides a proprietary, fully fledged hub-and-spoke production network and an IT platform that allows for consolidated and efficient LTL transportation within Germany and that is open to any non-member logistics service provider. The network HQ is responsible for maintaining, developing, and optimizing the production network and IT platform in order to ensure structural stability, operational efficiency, and system interoperability.

The network members are mainly responsible for feeding and defeeding the route network. In the course of their ordinary business activities, they acquire LTL consignments from their local customers and execute transportation services, such as local pickup and delivery, as well as operating regular line haul connection(s). As far as Alpha network operations are affected, the network partners have to adhere to the specifications (for example, quality) and operational instructions (for example, timetables for line hauls, process guidelines) issued by HQ.

The second LTL network is the Beta network. Beta also belongs to the top ten of the German LTL service providers, but exhibits quite different features compared to its rival Alpha. Only a few more than 10 logistics service providers, including a few large-sized firms, with the rest being medium-sized, form the Beta network, which has one central hub and 40 local depots throughout Germany. The network management unit Beta LLC is headquartered at the central hub and has about 150 administrative and operational employees. Beta’s financial endowment stems from the partners’ capital shares as well as handling and administration service fees. The resulting revenues are first used to cover the headquarters’ and the hub’s running costs. Remaining profits are eventually paid to the shareholding partners — just as possible deficits will also be compensated by these legally liable partners. As a consequence, substantial investments, for example, into the alliance’s infrastructure, cannot be made without the involvement of the respective shareholding partners. Network HQ organization is widely determined by its legal status as a limited liability company and its economic dependency on the relatively small number of alliance members (equity holders). Like Alpha, it consists of a management board, a supervisory board (chaired by the CEO of the largest investing partner), and a yearly general meeting, composed of all equity holding partners. In contrast to Alpha, the Beta alliance exhibits further organizational units for participative decision-making processes: regional groups, the supervisory committee, focus teams, and the partner meeting. Depending on the location(s) of the respective depot(s), every partner company is member of at least one regional group. Here, executive management representatives meet quarterly to discuss current regional problems and to exchange, assess, and select improvement initiatives. The supervisory committee in turn consists of one delegate from each regional group. The committee regularly discusses relevant region-spanning issues and prepares decision memos for the partner meeting, acting as a link between regional groups, focus teams, and the partner meeting. However, both the regional groups and supervisory committee can delegate topics to specialized focus teams for concrete elaboration. Focus teams are assembled as needed by partner company experts and Beta’s line and/or staff departments, such as marketing, IT, operations, and strategy. Overall, network partners possess extensive strategic, operational and design authority.

In its day-to-day business, Beta LLC as network HQ executes an operative coordination and control function, since all shipment data converges there. Moreover, the LLC’s employees take responsibility for central hub operations, line-haul timetables, alliance marketing support, IT system development, data clearing and performance monitoring, process standards, and dedicated staff training. However, unlike Alpha, the central management unit’s CEO and his staff are responsible for facilitating inter-partner exchange and participative decision processes with regard to network maintenance, strategy, and optimization. Therefore, they take care that all respective meetings proceed regularly, are prepared properly, and are attended by the correct representatives. Furthermore, Beta LLC enforces partner rule compliance, keeps control of all current project initiatives, and takes over implementation for major initiatives on behalf of the alliance partners. An overview of the key Alpha and Beta features is presented in table 3.

TABLE 3: Overview of Key Alpha and Beta Characteristics (as of 2008)

AlphaBetaNo. of membersRevenuesShipments>100 Shareholders> €100 million>5 million>10 Shareholders and associates> €100 million> 5 millionAlliance managementNetwork HQ as privately held limited liability companyNetwork HQ as privately held limited liability company, forums, workgroupsNetwork HQ’s responsibilityNetwork operations and designNetwork operations, network marketing (incl. tender management)Partner firms‘ responsibilityCustomer acquisition, Marketing, productionCustomer acquisition, production, network design (standard setting, etc.) through participation in forums and workgroupsOtherNo territory protection, multiple alliance membership, optional alliance network usageTerritory protection, single alliance membership, obligatory alliance network usageSource: adapted from Albers &Klaas-Wissing (2012)

Both alliances provide similar products and services within the same geographical area, resulting in similar provision requirements. Furthermore, they achieve and handle virtually similar revenues and shipments per year. Although present in the same business context and revealing very similar operational characteristics, both alliances differ in the way they cooperate in order to cope with their operation scale (that is, shipping volume and geographic density): whereas Alpha pools over 100 small member firms with low shipping volumes and restricted geographical scope, Beta integrates roughly a tenth of that number, but with partner firms of comparatively larger size and scope, respectively. Since coordination costs incurred by the alliance’s activities are to a large extent affected by the number of partner companies involved, Alpha, Beta and their respective member companies consequently have to deal with different organizational challenges in terms of cost-efficient partner integration and coordination. Alpha relies on high standardization levels, as well as on its administrative processes, and serves as a highly efficient operations platform for its members, although it does not allow customization to individual members’ needs. By contrast, Beta is a much more participative and flexible organization that reflects the requirement of catering to member needs and preferences.

The analysis shows that there is no “one best way” of alliance organization in the LTL business, since Alpha and Beta’s differing organizational designs seem to match the requirements of their specific situational settings. Their differences can be widely related to the different number of partner companies within the alliance and the quest for low coordination cost. In the highly competitive LTL industry, the examined alliance networks seem to have found effective and, at least temporarily, efficient governance arrangements that allow them to compete with the large and integrated logistics corporations. The substantial number of failing business networks in the LTL industry, albeit not all and exclusively related to ineffective and inefficient structures, support the view that the variety of effective organizational arrangements is not endless, and that networks need make sure that they identify and implement such effective organizational structures in order to provide the benefits that their members expect.

Therefore, business networks can be encouraged in that organizational forms are available that can contribute to their and their members’ competitive advantage. However, they also need to be cautioned in so far as the most effective and efficient forms must be tailored to their specific situations. In addition, member political interests and potential conflicts between the network management and members more often than not prevent implementing, or even identifying, the most effective organizational solutions, and therefore risk the well-being and survival of the network and at least some of its members.

Network organization structures and processes need to take the specific, idiosyncratic conditions of the network and its members into account to devise the most effective and efficient organizational solution. Networks therefore must understand “the situation”, i.e. understand the aims and needs of the own network, the characteristics of the industry and the environment in order to be able to design the network organization accordingly. In this context, generic designs can be starting points or reference points, but most likely will not correspond to any effective network governance model for a real-work business network.

Since it is also unlikely that every innovation, major progress, and new insight willbe generated locally, the permanent assessment and monitoring of own and competing networks is important. For this purpose, different business environments and industries should also be taken into account. Telecommunications providers may well learn from alliance networks in the airline industry, and trade fairs from the automobile industry.

Research shows that firms benefit from past alliances if they manage to effectively store, retrieve, and disseminate knowledge on former management practices, for example by forming dedicated positions or functions for alliance management purposes (Kale, Dyer & Singh, 2002).Member firms and network HQs are therefore most likely to benefit from their continuous involvement in identifying, addressing and solving network-related issues. However, despite the important role of experience in forming stable cognitive schemes and reaction repertoires (Albers & Heuermann, 2013), a certain degree of flexibility among members and network HQ needs to be maintained to allow for experimenting with different organizational solutions.

3.4. Summary

The three forms of network competition portrayed here, (1) competition in network formation, (2) competition in network composition, and (3) competition in network governance, focus on different, yet critical domains of competitionin network dynamics, and thereby illustrate that competitive interactionsin each of these domains need to be taken into account in network initiation and management. These can have major performance implications not only for the network but also for every network member. Competition in network formation refers to the most foundational domain of business networks, i.e. their principal purpose and thus, the reason for their existence. This type of competition especially highlights the instrumental nature of business networks for their members. Competition in network formation focuses on the essential elements of a business network: its members, and the resources that they bring into the network. Competition in network governance reiterates that it is not sufficient to be innovative, or to have an inspiring idea and a knowledgeable and competent team, but that member organization and orchestration, that is: their interplay, are non-trivial tasks that need to be performed reasonably well and in accordance with the specificities of the actual situation. Only then the potentials of the promising idea and the competence of the team members can be leveraged.

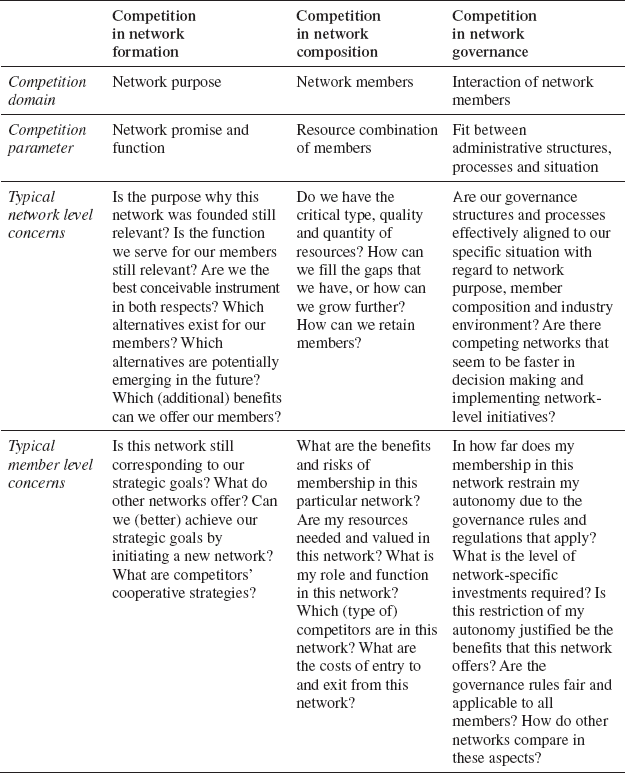

For each of these three types of competition typical concerns that decision makers on the network and member levels frequently encounter can be formulated (see table 4 for an overview). Some of them can be addressed by the management implications outlined in the respective sections of this chapter, others are only hardly subject to general and generic implications.

Additionally, it should be noted that these forms of network competition are not independent. Various relations exist, as figure 1 indicates: a relevant and convincing network purpose requires a “good” constellation of members and an effective governance system to materialize; a constellation of members that are willing to effectively combine their resources need a legitimate purpose and a fitting governance to do so; and a highly effective governance system is of little help if members lack critical resources, or diverge in their understanding and assessment of the purpose of their joint endeavor. Thus, networks and network members are subject to all three forms of network competition simultaneously — even though in varying, probably even fluctuating strength and prominence.

TABLE 4: Overview of three types of network competition, key characteristics and resulting concerns for decision makers on the network and member levels

4. CONCLUSION AND RELATIONS TO BUSINESS AND COMPETITION LAW

Business networks are highly interesting phenomena that have emerged as highly relevant arrangementsin the explanation of firm performance. The way in which networks shape competition for the single firm has two sides: It can be positive if firms realize the potential and use the opportunities provided by network formation and membership; it can also have negative repercussions if firms ignore or are unable to find adequate responses to rivals’ cooperative strategies. The above pointed out three forms of this network competition, presented one empirical study for each domain, and explicated some consequences for network and member firm management. Suggestions included differentiating (1) competition in network formation, (2) competition in network composition, and (3) competition in network governance.