По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

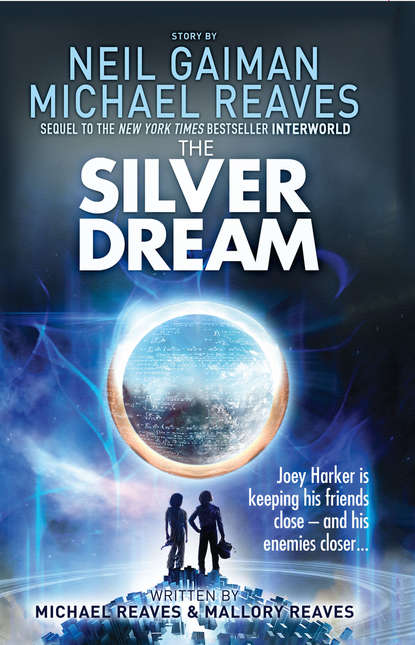

The Silver Dream

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Jaroux—male, the librarian. Loves knowledge, is friendly and quirky.

Jayarre—male, Culture and Improvisation teacher. Cheerful, charismatic.

J’emi—female, Basic Languages teacher.

Jernan—male, quartermaster. Strict and stingy with equipment.

Jirathe—female, Alchemy teacher. Body made from ectoplasm.

Joeb—male, team leader, senior officer. Laid-back, brotherly attitude.

Jonha—male, officer. From a magic world. Skin like tree bark.

Jorisine—female, officer. From a magic world. Elflike.

Joseph Harker (the Old Man)—male, the leader of InterWorld. Older version of Joey. Stern, has a cybernetic eye.

Josetta—female. The Old Man’s assistant. Friendly, well organized, no-nonsense.

Josy—female, officer, has long golden hair with knives braided into it.

(#ulink_0c5eb1f1-5ac9-55ab-b48f-2970fb194b93)

CALL ME JOE.

Please.

It’s not that I have anything against “Joey”—it’s a perfectly good name, and it’s worked fine for the first sixteen years of my life. But that’s the point. I’m sixteen now, almost seventeen, and the name “Joey” just doesn’t feel like me anymore. Which maybe isn’t surprising, given that I’ve met more versions of myself than Star Wars has clones. When you stop to think about it, I’ve probably got the biggest identity crisis of all time going, so if I want to drop one lousy letter from my name, I think I’m entitled.

I was trying to explain this to Jai, which wasn’t easy, considering that we and the rest of the team were pinned down by Binary scouts shooting what looked like elongated blobs of mercury at us, and Jai’s not the easiest person to talk to unless you happen to have a dictionary chip installed between your ears. Which I don’t.

He listened, returning fire with more mercury blobs (which are called “plasma pods” in case you’re wondering), and then asked, “Are you unambiguously certain?” Behind him, Jakon leaped on top of a power condenser, crouching all sleek and furry, snarling as she looked for more prey. The wolf girl version of me looked like she might be enjoying this a little. She always did, but I suppose there was nothing wrong with loving your job. . . .

“Excuse me,” Jai said crisply, aiming over my shoulder down the length of the big chamber in the abandoned power plant. He fired the emitter, which made a sort of thwip! sound. I caught a crazy, distorted glimpse of movement from behind me, reflected off the chest area of Jai’s encounter suit: a Binary scout on a grav-board, trying for a sneak attack. Then the plasma pod hit him and negated the binding force in his atomic nuclei, which is how Jai would’ve described it. Me, I’d just say he disappeared in a puff of smoke and a sound like zzzapht!!

This caused a momentary lull in the fighting on both sides, which I took advantage of to ask what he meant. “Huh?” I said. (I get a lot more mileage out of words than Jai does.)

“Are you unambiguously certain?” he repeated patiently. He pointed the emitter in various directions. Thwip. Thwip.

Next to me, J/O fired his laser-cannon arm at a group of attacking scouts. “That means are you sure,” he offered helpfully, and I rolled my eyes. J/O did have a dictionary chip installed between his ears, and took every opportunity to make me aware of it. I ignored him.

“That I want to change my nickname? Yes.”

“No, that your chronological age is in fact sixteen.”

I started to tell him that his brain had finally grown too big for his head, but stopped. He had a point.

Though we don’t time travel in the classic sense in the InterWorld organization, we all know that time itself isn’t independent, aloof, and serene from all the myriad worlds that make up the various versions of Earth. Though I’d never encountered any Earths on which time itself seemed subjectively altered—Earths on which everyone seemed to ta-a-a-l-lk-k . . . r-e-e-a-l . . . s-l-o-o-w . . . or Earths where everyoneranaroundliketheywereinanoldsilentmovieandtheyalltalkedlikethis!—still, most people knew that time passed quicker or slower in some planes as opposed to others. Just as it was also known that after some time spent in those worlds, your own time sense, not to mention your body, adjusted to the new temporal reality.

I’d been in quite a few such parallel planes in the time I’d been a member of InterWorld. Which meant that Jai had a valid reason for asking, but only up to a point. I might be, as far as I knew, older than my birthday said I was. Or younger. Problem was, there was no way to measure the rate that time passed “outside” the plane we were in. And even if there were, what about time spent in the In-Between, that crazy-quilt collision of various realities and worlds that a Walker used as a shortcut from one reality to the next? Besides, it was all subjective, tied in with consciousness, so really, you only were “as old as you felt.”

I said as much to Jai, who looked at me as if I’d just pointed out to him that the sky was blue. (Usually. On this world it was more greenish.) “Indubitably,” he said, and then he lost me again. “And are you unquestionably certain your haecceity is defined by your moniker?”

“My what?”

“Your moniker. Your name.”

“I know that one. My . . . hi-ex-it . . . ?”

“Haecceity. Your youness. The qualities that make you you, rather than me.”

“Even I didn’t know that one,” J/O admitted, looking like he was filing it away somewhere—which he likely was.

“That’s an ironic thing to ask,” I said, “considering that you are me. Or I’m you, whichever.”

“Yet we all possess qualities which render us unique. Haecceity is the particular characteristics of those qualities that make you you.”

Thwip. Thwip. Zzzapht!!

I pondered that as another rutabaga bit the dust. I was getting used to seeing it, which was both a relief and a disturbance, if you know what I mean. The emitter dissolved the atomic bonding, which meant no muss, no fuss. They just went poof—or zzapht. And they weren’t people in the same sense that we were. They looked human until you got up close; then their skin had a waxy, unfinished look, which made sense, since they were actually clones made primarily from cellulose and plant matter. The Binary was big on cookie-cutter assembly-line cannon fodder, just like HEX’s armies of choice were usually zombies. There wasn’t much point in feeling bad about killing something that was nine-tenths dead to begin with. But it still bothered me that it was bothering me less, if that makes any sense.

I was about to say something else to Jai, when I heard Josef approaching. Josef came from a world much denser than most of ours, so it wasn’t hard to recognize his heavy tread. “What’s up, Josef?” I asked, without turning my head. I was tracking another rutabaga.

He didn’t reply immediately, so I squeezed off my shot (thwip!) and glanced over my shoulder at him. “They’ve sent in reinforcements,” he rumbled, looking troubled.

“How many?” Jai asked, and I knew then it was bad, because Jai usually can’t ask anything in less than ten syllables. Josef shook his head.

“Too many to count quickly.”

J/O turned and looked at the nearest blank wall. “Tapping into an exterior security cam,” he said. J/O’s a cyborg version of me, from an Earth that is currently recovering from the Machine Wars. He’s got more hydraulic fluid circulating in him than blood, so when I watched the color drain from his face I knew something was very wrong. He was younger than me by a few years, and while he always handled himself well on missions—and made sure to point it out when he did—it was moments like this that I was reminded of his youth.

“Let’s see,” I said.

One of his eyes was cybernetic; it usually looked almost identical to his natural eye, save the circuitry going through it. That eye grew brighter, and on the wall there appeared a black-and-white projection of the outside. At first there was little to see: just more blasted masonry, exposed rebar, and the like. But then—

There was movement.

Lots of movement.

Rutabagas swarmed down the blasted, torn-up streets; over, around, and through walls; and even up from manholes and huge cracks in the pavement. There must’ve been a hundred in the first couple of minutes. And they just kept coming.

J/O had only tapped into the visual, not the audio, if there even was one. It really was eerie, seeing them coming, wave after wave, in utter silence.

And I realized that the silence also meant the hostilities had stopped inside the power plant. The veggie clones already in here with us had ceased their attack. Of course: No point in wasting more of their numbers when they can just sit back and wait. Six of us against five hundred or so of them . . .

Suddenly my deep and abiding concern over what I wanted to be called didn’t seem very important.

The walls and floor began to tremble. They were right outside.