По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

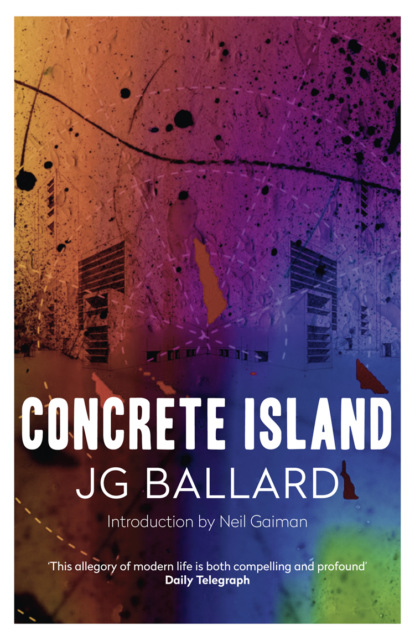

Concrete Island

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 23 – The trapeze (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 – Escape (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

The Sage of Shepperton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#u93bc0e2d-7cb2-5381-a8be-5e7d045ea8ef)

The day-dream of being marooned on a desert island still has enormous appeal, however small our chances of actually finding ourselves stranded on a coral atoll in the pacific. But Robinson Crusoe was one of the first books we read as children, and the fantasy endures. There are all the fascinating problems of survival, and the task of setting up, as Crusoe did, a working replica of bourgeois society and its ample comforts. This is the desert island as adventure holiday. With a supplies-filled wreck lying conveniently on the nearest reef like a neighbourhood cash and carry.

More seriously, there is the challenge of returning to our more primitive natures, stripped of the self-respect and the mental support systems with which civilisation has equipped us. Can we overcome fear, hunger, isolation, and find the courage and cunning to defeat anything that the elements can throw at us?

At an even deeper level there is the need to dominate the island, and transform its anonymous terrain into an extension of our minds. The mysterious peak veiled by cloud, the deceptively calm lagoon, the rotting mangroves and the secret spring of pure water together become out-stations of the psyche, as they must have done for our primeval forbears, filled with lures and pitfalls of every kind.

The Pacific atoll may not be available, but there are other islands far nearer to home, some of them only a few steps from the pavements we tread every day. They are surrounded, not by sea, but by concrete, ringed by chain-mail fences and walled off by bomb-proof glass. All city-dwellers know the constant subliminal fear of being marooned by a power failure in the tunnels of a subway system, or trapped over a holiday weekend inside a stalled elevator on the upper floors of a deserted office building.

As we drive across a motorway intersection, through the elaborately signalled landscape that seems to anticipate every possible hazard, we glimpse triangles of waste ground screened off by a steep embankments. What would happen if, by some freak mischance, we suffered a blow-out and plunged over the guard-rail onto a forgotten island of rubble and weeds, out of sight of the surveillance cameras?

Lying with a broken leg beside our overturned car, how will we survive until rescue comes? But what if rescue never comes? How do we attract attention, signal to the distant passengers speeding in their coaches towards London Airport? How, when faced with the task, do we set fire to our car?

But as well as the many physical difficulties facing us there are the psychological ones. How resolute are we, and how far can we trust ourselves and our own motives? Perhaps, secretly, we hoped to be marooned, to escape our families, lovers and responsibilities. Modern technology, as I tried to show in Crash and High Rise, offers an endless field-day to any deviant strains in our personalities. Marooned in an office block or on a traffic island, we can tyrannise ourselves, test our strengths and weaknesses, perhaps come to terms with aspects of our characters to which we have always closed our eyes.

And if we find that we are not alone on the island, the scene is then set for an encounter of an interesting but especially dangerous kind…

Introduction (#u93bc0e2d-7cb2-5381-a8be-5e7d045ea8ef)

BY NEIL GAIMAN (#u93bc0e2d-7cb2-5381-a8be-5e7d045ea8ef)

Memories of J. G. Ballard, Jim to his friends – and I was never one of them, being too young and arriving too late in the world of writers, but still, he’s Jim Ballard as I was introduced to him, like the boy in Empire of the Sun. He was standing beside William Burroughs at an art opening, affable and dry and avuncular, thoroughly suburban, as he observed the eighties artistic freakshow that surrounded him, somehow managing to be both part of it and detached. I did not talk to him, then or any of the times I could have done. I was awed, and he always seemed too near and too far away.

Children, the kind who read, read everything that they find in the house; they read their parents’ books (the ones the parents had as children, the ones they had as adults); they read Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe alongside Isaac Asimov’s TheCaves of Steel; The Coral Island then Dune Messiah; The Islandof Adventure beside Conan the Adventurer: they read all the books they can because the books are there, and because books offer information and escape. Or I did, anyway. Also, I knew we were all headed for the future, and I wanted to know what things would be like when we got there, surrounded by robots, with our hand-held communications devices.

Which meant that, growing up, two of my favourite books were The Crystal World by J. G. Ballard – a strange apocalypse I barely understood, and to which I was attracted by the cover, showing a beautiful, glassy landscape, and the back-cover blurb, which told me that this was about people exploring the Amazonian rainforest, trying to find out why the world was becoming crystal – and SF 12, edited by Judith Merrill, the book in which I discovered R. A. Lafferty and William Burroughs, Samuel R. Delany and Kit Reed, Carol Emshwiller and Fritz Leiber, Brian Aldiss and Tuli Kupferberg and a host of authors and ideas, including a story called ‘The Cloud-Sculptors of Coral D’, by J. G. Ballard, about a cloud sculpture and the men who fly small planes, about love and about murder.

These books meant that Ballard was, in my head, part of the club of SF writers, the people who wrote things I loved (even if I did not entirely understand them), and this meant I read everything by him that I could find. And when, aged thirteen, I changed schools, I discovered a school library filled with books that had not been in my previous school library: I found Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books there, and TheMaster and Margarita and 1984 (which I read mostly to understand Bowie’s Diamond Dogs and because there were jokes in the Alan Coren 1984 parody in Punch I suspected I was missing), and, on a high shelf, a tiny clutch of Ballard novels.

I read Crash first. I did not understand it, but I loved the writing, loved the smell of leather upholstery and the jewelled glitter of broken glass on the motorway. It seemed peculiarly intellectual: Elizabeth Taylor and crashing cars for sexual pleasure were both very abstract concepts for a teenager who had not been a teenager for very long.

Then I read Concrete Island, and I was in love.

I did not read then for character or for language (although I could be hooked by either and responded to both); I read for story, and in Concrete Island, I recognised a story, and came upon a story I recognised. It was Robinson Crusoe: here was a man, Robert Maitland, stranded on an island, cut off from civilisation, learning how to feed himself and survive, obsessed by the need to get off the island, get back to civilisation, to his wife, to his company, to his mistress, to his world.

I was of an age where I was beginning to see metaphor and pattern. He’s on an island, I thought, and he’s been on an islandhis whole life. It was a revelation.

I thrilled, reading it then, as I thrill each time I reread it, to Maitland’s problem-solving efforts in the first few chapters: his plans to send up signal flares, his search for drinkable water, his attempts to get people to see him and stop. And to his joy at the thrown-away chips. Robinson Crusoe had breadfruit and other foodstuffs alien to a small boy in Sussex. He didn’t have a lorry driver’s discarded chips.

I was saddened and thrilled when Maitland found that he was not alone on his island: Crusoe had Friday, had that footprint in the sand. Maitland had two people, whose behaviour towards him seemed pretty much right: I was a schoolboy, after all, and casual cruelty was usual. Lord of the Flies and Unman, Witteringand Zigo both seemed, to me, realistic about the way the children around me behaved, or would behave given half a chance.

Reading Concrete Island now, I read it with adult eyes. And if you have not read the book, stop reading this introduction here. The story is too good to spoil for you, after all.

I marvel at Ballard’s ability to bring the Coral Island home, to recognise that a traffic island was, for someone stranded on it, as remote as the South Seas. I am fascinated by the politics of Friday, and the way that Ballard breaks that role in two, and subverts it; and how savage Maitland needs to become in order to gain dominion over his Island Kingdom. Friday, the savage that Crusoe rescues, who knows more of the island and the ways of survival than Crusoe ever will, becomes two survivors: a mentally subnormal acrobat, and a young woman whose tragedies are never explained, only implied, and who leaves the island and returns, a heart-hurt whore who no longer fits the world she fled. Both people whom Maitland would look down on in everyday life, both people on whom he finds himself depending for his survival.

I admire the way the island is a palimpsest: the world, the town, before the motorway existed shows through, just as Robinson Crusoe shows through in Concrete Island, from time to time.

I did not understand when I was a boy that the best way to prepare for my adult future would be to read the work of J. G. Ballard. That authors offering me generation starships and galactic empires were a distraction: that it was Ballard who was writing the world I would grow into. I don’t think I understood that until the crash-death of Princess Diana, and I knew that I had been here before, and in whose pages.

Concrete Island is of its time, an artefact, but one could write something very similar now. One would need to deal with the mobile-phone issue – probably destroy it in the initial crash – but I wonder how many of us would actually stop, or let anybody know, if we saw the filthy man in the motorway island, and how many of us are able to escape the islands on which we now find ourselves marooned.

Cambridge, 2014

1 Through the crash barrier (#u93bc0e2d-7cb2-5381-a8be-5e7d045ea8ef)

SOON after three o'clock on the afternoon of April 22nd 1973, a 35-year-old architect named Robert Maitland was driving down the high-speed exit lane of the West-way interchange in central London. Six hundred yards from the junction with the newly built spur of the M4 motorway, when the Jaguar had already passed the 70 m.p.h. speed limit, a blow-out collapsed the front nearside tyre. The exploding air reflected from the concrete parapet seemed to detonate inside Robert Maitland's skull. During the few seconds before his crash he clutched at the whiplashing spokes of the steering wheel, dazed by the impact of the chromium window pillar against his head. The car veered from side to side across the empty traffic lanes, jerking his hands like a puppet's. The shredding tyre laid a black diagonal stroke across the white marker lines that followed the long curve of the motorway embankment. Out of control, the car burst through the palisade of pinewood trestles that formed a temporary barrier along the edge of the road. Leaving the hard shoulder, the car plunged down the grass slope of the embankment. Thirty yards ahead, it came to a halt against the rusting chassis of an overturned taxi. Barely injured by this violent tangent that had grazed his life, Robert Maitland lay across his steering wheel, his jacket and trousers studded with windshield fragments like a suit of lights.

In these first minutes as he recovered, Robert Maitland could remember little more of the crash than the sound of the exploding tyre, the swerving sunlight as the car emerged from the tunnel of an overpass, and the shattered windshield stinging his face. The sequence of violent events only micro-seconds in duration had opened and closed behind him like a vent of hell.

‘… my God…’

Maitland listened to himself, recognizing the faint whisper. His hands still rested on the cracked spokes of the steering wheel, fingers splayed out nervelessly as if they had been dissected. He pressed his palms against the rim of the wheel, and pushed himself upright. The car had come to rest on sloping ground, surrounded by nettles and wild grass that grew waist-high outside the windows.

Steam hissed and spurted from the crushed radiator of the car, spitting out drops of rusty water. A hollow roaring sounded from the engine, a mechanical death-rattle.

Maitland stared into the steering well below the instrument panel, aware of the awkward posture of his legs. His feet lay among the pedals as if they had been hurriedly propped there by the mysterious demolition squad which had arranged the accident.

He moved his legs, reassured as they took up their usual position on either side of the steering column. The pedal pressure responded to the balls of his feet. Maitland ignored the grass and the motorway outside and began a careful inventory of his body. He tested his thighs and abdomen, brushed the fragments of windshield glass from his jacket and pressed his rib-cage, exploring the bones for any sign of fracture.

In the driving mirror he examined his head. A triangular bruise like the blade of a trowel marked his right temple. His forehead was covered with flecks of dirt and oil carried into the car by the breaking windshield. Maitland squeezed his face, trying to massage some expression into the pallid skin and musculature. His heavy jaw and hard cheeks were drained of all blood. The eyes staring back at him from the mirror were blank and unresponsive, as if he were looking at a psychotic twin brother.

Why had he driven so fast? He had left his office in Marylebone at three o'clock, intending to avoid the rush-hour traffic, and had ample time to cruise along in safety. He remembered swerving into the central drum of the Westway interchange, and pressing on towards the tunnel of the overpass. He could still hear the tyres as they beat along the concrete verge, boiling off a slipstream of dust and cigarette packets. As the car emerged from the vault of the tunnel the April sunlight had rainbowed across the windshield, momentarily blinding him …

His seat belt, rarely worn, hung from its pinion by his shoulder. As Maitland frankly recognized, he invariably drove well above the speed limit. Once inside a car some rogue gene, a strain of rashness, overran the rest of his usually cautious and clear-minded character. Today, speeding along the motorway when he was already tired after a three-day conference, preoccupied by the slight duplicity involved in seeing his wife so soon after a week spent with Helen Fairfax, he had almost wilfully devised the crash, perhaps as some bizarre kind of rationalization.

Shaking his head at himself, Maitland knocked out the last of the windshield with his hand. In front of him was the rusting chassis of the overturned taxi into which the Jaguar had slammed. Half hidden by the nettles, several other wrecks lay nearby, stripped of their tyres and chromium trim, rusty doors leaning open.

Maitland stepped from the Jaguar and stood in the waist-high grass. As he steadied himself against the roof the hot cellulose stung his hand. Shielded by the high embankment, the still air was heated by the afternoon sun. A few cars moved along the motorway, their roofs visible above the balustrade. A line of deep ruts, like the incisions of a giant scalpel, had been scored by the Jaguar in the packed earth of the embankment, marking the point where he had left the road a hundred feet from the overpass tunnel. This section of the motorway and its slip roads to the west of the interchange had been opened to traffic only two months earlier, and lengths of the crash barrier had yet to be installed.

Maitland waded through the grass to the front of his car. A single glance told him that he had no hope of driving it to a nearby access road. The front end had been punched into itself like a collapsed face. Three of the four headlamps were broken, and the decorative grille was meshed into the radiator honeycomb. On impact the suspension units had forced the engine back off its mountings, twisting the frame of the car. The sharp smell of anti-freeze and hot rust cut at Maitland's nostrils as he bent down and examined the wheel housing.

A total write-off – damn it, he had liked the car. He walked through the grass to a patch of clear ground between the Jaguar and the embankment. Surprisingly, no one had yet stopped to help him. As the drivers emerged from the darkness below the overpass into the fast right-hand bend lit by the afternoon sunlight they would be too busy to notice the scattered wooden trestles.

Maitland looked at his watch. It was three eighteen, little more than ten minutes since the crash. Walking about through the grass, he felt almost light-headed, like a man who has just witnessed some harrowing event, a motorway pile-up or public execution… He had promised his eight-year-old son that he would be home in time to collect him from school. Maitland visualized David at that moment, waiting patiently outside the Richmond Park gates near the military hospital, unaware that his father was six miles away, stranded beside a crashed car at the foot of a motorway embankment. Ironically, in this warm spring weather the line of crippled war veterans would be sitting in their wheel chairs by the park gates, as if exhibiting to the boy the variety of injuries which his father might have suffered.