По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

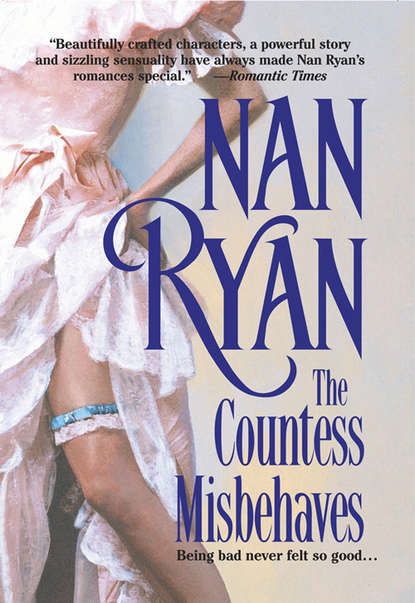

The Countess Misbehaves

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She raised her arms above her head and sighed once more. And she gave silent thanks that the man to whom she was officially engaged, was a kind, cultured nobleman.

Madeleine smiled as she pictured Desmond Chilton, Fourth Earl of Enfield, whom she was to wed next spring. A distant cousin whom she had known since childhood but had rarely seen, Lord Enfield had left their native England more than a decade ago.

The earl had settled in New Orleans where Madeleine’s dear uncle, Colfax Sumner—her deceased mother’s only sibling—had lived for the past forty-five years. The two men had become good friends and when she had visited her uncle during the past summer, the handsome blond earl had spent a great deal of time at Colfax’s French Quarter mansion. A week before she was to return home to England, the earl proposed and she had accepted.

Lord Enfield would, she felt sure, treat her as a wife should be treated. He clearly adored her. And, if she was less than passionately in love, that presented no weighty problem as far as she was concerned. She much preferred being the ‘beloved’ as opposed to the ‘lover.’ Desmond was most definitely the lover. She his beloved. Which was as it should be, as it would remain.

Never again would she risk being humiliated by a mere mortal man.

Armand de Chevalier remained on deck for the next hour, strolling unhurriedly from stern to bow as the huge vessel moved slowly out of the Liverpool harbor and made its way to the open sea.

Excited, well-dressed travelers had lined the ship’s railing, waving to those left behind. Others, like Armand, promenaded around the ship’s polished decks, greeting fellow voyagers, laughing, talking, anticipating an enjoyable adventure.

Many of those happy passengers were, of course, women. Some with husbands or family members. Others traveling together in groups of two or three. Still others were alone, save for a servant or attendant. There were, Armand noted, dozens of unattached, attractive women.

But not one captured his attention as the stunning woman with the red-gold hair. He couldn’t get her out of his mind. He wanted to see her again, and he searched the milling crowds, hoping that perhaps she would take a stroll once they were on the open sea.

She did not.

After a couple of frustrating hours, Armand gave up and made his way to the gentleman’s tavern. There in the darkly paneled club, he stepped up to the long polished bar, ordered a bourbon straight and downed it in one swallow.

As the barkeep poured another, Armand couldn’t help overhearing a conversation taking place between two gentleman standing next to him who were sipping port.

“She’s a British noble lady,” said a short, balding gentleman with muttonchop sideburns. “The only child of the fifth earl of Ballarat and his American-born wife, both of whom are now deceased.”

“Is she now?” replied his drinking companion, a tall, cadaver-thin man in a brown linen suit with a boutonniere in his buttonhole.

Armand knew, instinctively, that they were talking about his red-haired beauty. “Excuse me, gentlemen,” he said and the port-drinking pair turned to look at him. “Does the noblewoman of whom you are speaking happen to have red hair?”

The tall, skinny fellow nodded, and said with a slight touch of wistfulness, “An unusual shade of red-gold that is incredibly striking against her pale-white skin.”

“Who is she?” Armand asked bluntly.

“Why she’s Lady Madeleine Cavendish, the flame-haired Countess,” said the short man with the muttonchop sideburns. “One of the most renowned beauties in all Europe.”

“Undoubtedly,” said Armand before he downed his second whiskey. “Gentlemen,” he said as he nodded good-day then turned and walked out of the tavern.

Armand was unfazed by her lofty status. Un-bothered by the fact that she was a Countess. An inherently confident man, Armand had learned, long ago, that beneath fine satins and laces, often beat the passionate heart of a hot-blooded woman.

He’d bet everything he owned that the lovely Lady Madeleine Cavendish was such a woman.

Two

After a restful afternoon nap followed by a long leisurely bath, Madeleine Cavendish was again feeling like her old self. Relaxed. Self-assured. Looking forward to her first evening at sea.

When the blinding summer sun had finally slipped below the horizon and full darkness had fallen, Madeleine was humming happily as the surprisingly talented Lucinda meticulously dressed her long hair. It took a good half hour, but when Lucinda had finished, Madeleine’s heavy locks were skillfully fashioned into a shiny coronet of thick braids atop her elegant head. The style was quite flattering to Madeleine as it accentuated her graceful, swanlike neck and beautiful throat.

Madeleine had chosen, for the first dinner at sea, a shimmering green silk ball gown with a low-cut bodice, an uncomfortably tight waist, and billowing skirts that spilled attractively over yards and yards of crinoline petticoats.

By ten minutes of nine she was fully dressed and ready for dinner. But she waited another half hour before leaving the stateroom.

Arriving fashionably late, she swept into the immense dining hall with its blazing chandeliers, deep lush carpet and gleaming sandalwood walls. A uniformed steward ushered her directly to the captain’s table. A dozen diners were seated at the enormous round, white-clothed table.

All the gentlemen stood as a chair was pulled out for her. Nodding and smiling as she was presented to the well-dressed group, Madeleine noticed that one table companion was even later than she. The gilt chair next to hers was vacant. Perhaps the guest who was to be seated there had come down with a bad case of mal de mer. Poor miserable soul. She recalled, all too well, her first crossing years ago, when she had suffered from sea sickness.

As a white-jacketed waiter shook out a large linen dinner napkin and draped it across her silk-covered knees, Madeleine glanced up and saw the stranger from the railing. He was dressed impeccably in evening clothes and was making his way across the crowded room.

Dear lord he was coming straight toward the captain’s table!

Lady Madeleine stiffened. She gritted her teeth as he pulled out the empty chair on her right and sat down. The captain made the introductions and she learned her rogue was Armand de Chevalier, a New Orleans native on his way home after a lengthy summer stay in Paris. The elderly, gray-haired gentleman on her left, a New York banker, leaned close and whispered that de Chevalier was an aristocrat. A wealthy Creole who often traveled to Europe. He was, it was rumored, of the chacalata—the highest born of the Creole elite. Madeleine nodded. She knew that the haughty Creoles were the descendants of the early French or Spanish settlers who had been born in America. She also knew that they were considered the nobility of New Orleans.

Conversations resumed. Diners began to sample the vichyssoise. Armand de Chevalier turned away to politely reply to a question from a stout, expensively dressed woman seated on his other side.

Lady Madeleine suffered a mild twinge of alarm knowing that she and this raffish Creole were to be dwelling in the very same city. At the unsettling prospect, she involuntarily shivered.

“Are you chilly, my Lady?” Armand de Chevalier, turning his full attention to her, softly inquired. “If so, I could…”

“I am quite comfortable, thank you, Mr. de Chevalier.” She icily set him straight and reached for her wineglass.

From the corner of her eye she saw that the Creole’s full lips were turned up into a hint of a sardonic grin. Her dislike and distrust of the man increased.

It was, for Madeleine Cavendish, a miserable meal. Her usual healthy appetite missing, she pushed the food around her china plate and forced herself to smile and engage her fellow diners in idle conversation. All but de Chevalier. She said nothing to him. And, further, she silently, subtly let him know that she was not interested in hearing more about him nor did she intend to tell him anything about herself.

He didn’t press her.

Still, she was greatly relieved when at last the seven-course meal finally came to an end.

At the captain’s insistence, the smiling countess courteously allowed the beaming, white-haired ship’s officer to escort her into the ship’s mirrored ballroom. Leaving Armand de Chevalier behind, Madeleine immediately began to relax and enjoy herself.

Lavishly dressed dancers were spinning about on the polished parquet floor as a full orchestra in evening wear played a waltz. Warmed by the wine and relieved to be free of the bothersome Creole, Lady Madeleine was gracious when the aging captain lifted his kid-gloved hand and led her onto the floor.

She smiled charmingly as the barrel-chested captain turned her awkwardly about. And she laughed good-naturedly when he stepped on her toes and quickly assured him she was unhurt, no harm done.

Her smile was bright and genuine as the captain, soon wheezing for breath and perspiring heavily, continued to clumsily turn her about on the floor.

But her smile evaporated when Armand de Chevalier appeared and tapped the Captain on the shoulder. He brashly cut in, decisively took her in his arms and deftly spun her away.

She was trapped. Everyone was watching. The other dancers abruptly stopped dancing to watch the Countess and the Creole. Madeleine couldn’t make a scene. She couldn’t forcefully push de Chevalier away and storm out of the ballroom. She was left with no choice but to smile and endure the dance.

Madeleine’s smile was forced.

She was as stiff as a poker.

At least at first. But that quickly changed. The Creole was such a graceful dancer and so incredibly easy to follow, Madeleine—who had always loved dancing—found herself relaxing in his arms. And enjoying herself. Too much.

Soon she was no longer aware of the watching crowd. She was aware of nothing and no one save the man who held her and turned her and spun her about. His lean body barely brushed her own, yet she sensed his every movement as if she were pressed flush against his hard male frame. It was as if they were one body, hers so finely attuned to his, she could easily anticipate even the slightest nuance of movement before it took place.

It was strange.