По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

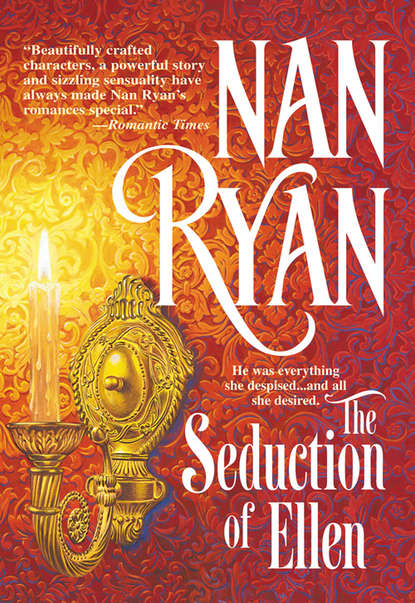

The Seduction Of Ellen

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He looked clean.

But he didn’t look harmless.

Ellen realized she was holding her breath. She didn’t want to get off the train. She didn’t want to encounter Mister Corey. She didn’t want to talk to him. She didn’t want him to drive her home. And she sure didn’t want him to kiss her.

As she made her way down the narrow aisle toward the car’s door, Ellen stiffened her spine and silently lectured herself. Never let him see that you are nervous. Insult him before he has a chance to upset you. It’s the only thing his kind understands.

Ellen stepped down from the train, tensed, expecting the dark devil to hurry forward, grab her off the steps and attempt to kiss her again. To her surprise, nothing of the kind happened. She looked about and saw that Mister Corey was still leaning against the pillar, unmoving, his arms crossed over his chest. What kind of game was he playing now?

Frowning, Ellen stepped down onto the platform, lifted her valise with effort and headed into the busy terminal. She glanced at Mister Corey out of the corner of her eye and felt her temper rise. He was making no move to come to her, to relieve her of her heavy suitcase, to assist her in any way.

Ellen went completely through the huge, crowded terminal and out onto the sidewalk in front of the station. She was raising her hand for a carriage when Mister Corey stepped up beside her, took the valise and said, “Welcome home, Ellen.”

She did not return the greeting. “Where is the carriage?”

Inclining his head, Mister Corey took her arm. “Just down the sidewalk about twenty yards. Think you can walk that far?”

“I can walk all the way home if I have to,” she warned, pointedly freeing her arm from his loose grasp.

“Then why don’t you?” he coolly challenged.

Her head snapped around and she glared at him. “Oh! I have,” she said in clipped tones, “had just about enough of you and—”

“I don’t believe you,” he cut in smoothly. His gaze briefly lowering to her lips, he said, “I don’t think, Ellen, that you’ve had nearly enough of me.”

“Are you blind and deaf?” she said, flustered and annoyed. “Don’t you know that you disgust me?”

They had reached the parked carriage. Mister Corey stepped close, put his hands to Ellen’s waist and lifted her up onto the leather seat. He placed her valise in the back and climbed up beside her.

“Your kiss,” he said softly, looking directly into her eyes, “was not the kiss of a woman who finds me disgusting.”

Ellen’s eyes narrowed. “I did not kiss you, you kissed me and I most certainly—”

“You kissed me back.”

“For heaven’s sake! Try and get this through your thick skull, Mister Corey, I did not want you to kiss me. I did not kiss you back. And I forbid you to ever kiss me again! Now, please, kindly just drive me home!”

Mister Corey smiled, nodded, unwrapped the long leather reins from around the brake handle and guided the horse and carriage out onto the busy thoroughfare. He made several attempts at small talk, but Ellen refused to respond.

He knew how to get a rise out of her.

“Was your homesick baby boy happy to see you?” he asked. No reply. Ellen stared straight ahead, acting as if she had not heard him. He knew she had. He pressed on. “Is he a mama’s boy?”

The insult of his question unleashed an angry diatribe from Ellen. Turning, she snapped, “My son is not a baby and he most definitely is not a mama’s boy. Christopher is a man and he has proven it.” She gave him a sneering look and added, “But then, that’s something you would know nothing about. You’ve probably never even heard of the Citadel, much less know what a great honor it is to attend the prestigious South Carolina military academy. Only the brightest and the best enter those gates and many of them are gone within days or weeks, unable to stand up to the rigid rules of the institute.”

“Is that a fact?”

“It most certainly is! And that is exactly as it should be. Those who are weeded out, and there are many, do not belong there. The academy’s goal is to make brilliant, steely-nerved officers of fine, intelligent young men like my son. I assure you that no fools or cowards or weaklings graduate from the Citadel.” She gave his lean frame an assessing glance, and asked, “Do you think you could have made it, Mister Corey?” Her tone, as usual, was condescending. “Could you have withstood the harsh discipline and intense punishment a plebe endures? Or would you have been too much of a coward?”

Ellen was looking directly at him when she asked, so she noticed the tension in his jaw. She immediately recalled the same thing happening the day Alexandra had suggested he accompany her to Charleston.

She was curious, but in an instant his expression changed and he said in a flat, drawling tone, “Looks like you’ve found me out, Ellen Cornelius. Yesiree, the truth is I’m a sniveling, quivering, trembling coward.” He laughed then.

She did not. “It isn’t funny, Mister Corey. I would think you would at least have enough pride to be ashamed to admit that you are a coward.”

“There was a time, long ago, when I was. But now I’m used to the label and it doesn’t sound that distasteful anymore. There are worse things to be called.”

“Yes, I suppose there are. Like swindler or cheat or thief,” she said hatefully, a smirk on her face.

“Perhaps, but I know some that are worse.” He pinned her with his night-black eyes. “Like toady or bootlick or kowtower.”

Ellen’s face instantly flushed with hurt and anger. Her green eyes flashing with fury, she said, “Insult me if you will. What you think of me is of no importance whatsoever. I do not need—nor want—your approval.”

“I don’t believe you,” he calmly replied.

In the 1890s America’s privileged took great pride and pleasure in showing off the expensive toys their vast wealth could provide. And so it was a period of the most splendid and ornate private railroad cars man could imagine. The wealthy all owned them, even if they seldom or never traveled. For the snobbish upper crust, the private rail car was an absolute necessity. The quintessential exhibition of ostentatious elegance.

Of all the private rail cars, none were finer than the sleek, gleaming ebony car with the gold script lettering on the door. The elegant car belonging to one of America’s richest women, Miss Alexandra Landseer.

Commissioned by the Pullman Company at the beginning of the decade, it had taken the company more than a year to finish the luxurious conveyance.

The delay was not the fault of Pullman, but of the persnickety lady who was to own the car. The interior had been changed no less than half a dozen times because Alexandra couldn’t make up her mind as to what she wanted. The harried workmen would think that they had finally completed the Landseer job, only to be told by a frowning Alexandra, bejeweled hands on her hips, that “No, this just won’t do! The bedroom is too large, the sitting room too small! All these walls must be torn out. You’ll simply have to start over. I will not pay you a penny until I get exactly what I want!”

And so it had gone for the entire year.

But, giving the devil her due, when finally the rail car had passed Alexandra’s discriminating inspection, it was a rolling wonder.

Inside, intricately carved boiseries exhibited the craftsmen’s infinite capacity for detail. A composite observation-sleeping car, the Lucky Landseer boasted a marble bathtub with gleaming gold fixtures. In the spacious sitting room, beneath a vaulted ceiling heavily embellished with Gothic fretwork, sat a handsome, oversize sofa and two matching easy chairs. The pale blue velvet furniture rested upon a thick, plush Aubusson carpet of blue and beige.

At the rear of the handsome room, a door opened onto an observation deck. A waist-high railing of beautifully carved iron lace bordered the small open-air deck. A narrow steel ladder went from the floor of the deck to the car’s top.

There was no furniture of any kind on the observation deck, although there was plenty of space. Alexandra saw no need for chairs or a settee. She had absolutely no interest in sitting out in the open, and it was always her own comfort that concerned her, no one else’s.

If Ellen or any invited guests wished to spend time on the observation deck, they simply would have to stand.

On the other side of the living room, in the car’s opulent bedroom, all the windows were draped with ice-blue velvet curtains. Alexandra never allowed those heavy drapes to be opened. She stated unequivocally that when she was inside her boudoir, she did not want some unwashed peasant along the tracks looking in at her.

The bedroom was capacious and comfortable and decorated with heavy carved furniture, gold-framed mirrors, marble statuary and handsome globed lamps and sconces. Beautiful artwork graced the wood-paneled walls.

Alexandra thought the room ideal.

Ellen did not.

It would have been, had it been hers alone. But the room was Alexandra’s and Ellen was forced to share with her aunt. Two specially built beds, covered in pale blue velvet spreads, were separated by only a small night table. The lack of privacy made Ellen dislike traveling in the splendid car.

But, tomorrow she would be trapped inside the velvet prison for several long days and nights as the train rolled westward.

Ellen exhaled loudly. Tonight, the eleventh of May, 1899, was the last night she’d spend in the quiet serenity of her own bedroom for many weeks.